Aston Martin's Grand Prix Cars

Atlas F1 Senior Writer

James Bond made the legendary Aston Martin marque famous on the silver screen, but not even Jim Clark and Carroll Shelby could make Aston Martin anything more than a bit player in Grand Prix racing. Atlas F1's Thomas O'Keefe looks back at the history of the famous British car and explains why it hasn't made it big in Formula One

Although Aston Martin ultimately became more famous in cinematic history for the appearance of Sean Connery in the elegant silver birch Aston Martin DB5 in the 1964 film "Goldfinger" (and later in "Thunderball") than it ever would become in Grand Prix history, it is easy to see why wealthy Yorkshire industrialist David Brown - who bought Aston Martin in 1947 after seeing a classified ad in the The Times offering the legendary British marque for sale - thought at the outset that he had the right elements at Aston Martin to become a Grand Prix constructor.

Imagine what a Grand Prix cocktail you could conjure up with a mix of the following ingredients, all of which Brown had at his disposal: a proud tradition in sportscar and endurance racing at LeMans and the Mille Miglia that would ultimately lead Aston Martin to winning LeMans and the World Sports Car Championship in 1959, legendary team manager John Wyer running the show from the pits along with ex-Grand Prix driver Reg Parnell who also drove Aston Martin sports cars, Carroll Shelby, Roy Salvadori and Maurice Trintignant as the drivers and Aston Martin's battle-tested six-cylinder sports car engine as the belly of the beast. And yet, this promising combination of elements failed to produce a successful Grand Prix team and the reasons for that failure are still the subject of speculation forty years on.

To be sure, David Brown was already on notice as to what he was getting himself into in becoming a Grand Prix constructor. Along with fellow-British businessman Tony Vandervell who created the Vanwall team, Brown had been one of the British motor industry moguls of the British Motor Racing Research Trust that supported what became BRM's ill-fated V-16 cylinder car circa 1950-51, which was a bust. Amazingly, having had that baptism of fire, Aston Martin in the late 1950s repeated some of the same mistakes BRM made in the early 1950s, but without achieving ultimate redemption as BRM did when Graham Hill brought the Constructors' Championship to BRM in 1962.

Vanwall also achieved success, scoring 9 Grand Prix wins (the same number as Mercedes-Benz, Maserati, Matra and Ligier) and winning the 1958 Constructors' Championship before it too exited Grand Prix racing in 1959 for a combination of seasons, principally Tony Vandervell's health and the tragic death of Stuart Lewis-Evans as a result of a fiery accident in a Vanwall at the end of the 1958 season.

But Aston Martin did not fare as well as Vanwall or BRM in Grand Prix racing. Timing is everything in life, in the movies and in Grand Prix racing and the conventional wisdom as to Aston Martin is that the company took too long to do too little and by the time the enterprise was up and running it was too late to matter.

Meanwhile, back in the chilly Midlands of England just weeks before Moss's triumph, Aston Martin had finally gotten around to testing its prototype Grand Prix car, the DBR4/250, which had been on the drawing boards at the factory in Feltham literally for years but had taken second place to the principal obsession of the company, which was to win LeMans.

Reg Parnell, a team manager and veteran driver who was no longer actively driving in Grands Prix but managed Aston Martin's sportscar team, participated in the December 1957/January 1958 testing process along with Roy Salvadori, an active Grand Prix driver who had driven rear-engined Coopers, but one who had not been in the Argentine race to see Moss vanquish the Ferrari Dinos and Maserati 250Fs with the diminutive rear-engined Cooper. Neither of these two test drivers were yet in a position to question the basic architecture of the Aston Martin Grand Prix car: a conventional front-engined Maserati 250F-looking type car, somewhat more svelte than the Maserati.

And the prototype DBR4/250 car certainly looked and sounded the part, sporting the British racing green fit and finish of the impeccably prepared Aston Martin sports cars and a derivative of the melodious Aston Martin RB6 sportscar engine. Besides that, everyone knew Stirling Moss was a champion-in-the-making and had run the Cooper in the Argentine race on one set of tires with no pitstops, the kind of one-off, tricked up victory that happens in racing. And only the Ferrari and Maserati teams had made the long trip to Buenos Aires so the competition that made the race was not entirely representative, with only 10 cars showing up on the grid.

But then it happened again. At the very next Grand Prix five months later, the Monaco Grand Prix on May 18th 1958, Maurice Trintignant, in an upgraded Rob Walker-entered Cooper T45 with a 2.01 litre Climax engine won the race against the entire Grand Prix establishment - Ferrari, Maserati, Vanwall, BRM and Lotus - proving that Moss's Argentine victory was not a fluke but a harbinger of things to come.

Aston Martin, like the Indianapolis 500 front-engined roadster-builders of the early 1960s, did not see the handwriting on the wall or, in Aston Martin's case, were too busy to worry about it. By the time of the 1958 Monaco Grand Prix, Aston Martin's resources were fully concentrated on the race in June 1958, LeMans, and a full factory effort of three Aston Martin DBR1s as well as a supporting older 1955-vintage Aston Martin DB3S driven by privateers Peter and Graham Whitehead meant Aston Martin was pulling out all the stops for the 1958 LeMans.

Today, Aston Martin's toniest product is called the V12 Vanquish; the 1958 Aston Martin Grand Prix car could well have been called the "Languish" for all the neglect it received during this period. And the worst part of it was that Aston Martin had a horrible 1958 LeMans in the end, with the 3.0 litre V12 Ferrari Testarossa winning it under conditions of persistent rain, the entire Aston Martin factory team having been retired and only the privateer DB3S in the hands of the Whitehead brothers surviving the monsoons to salvage the honor of Aston Martin.

But by the Spring of 1959, Aston Martin was at its professional zenith, girding itself for a final assault on LeMans and simultaneously preparing the Grand Prix car for its debut. Although the DBR4/250 was not ready to race soon enough for the traditional non-championship season opener, the Glover Trophy at Goodwood on March 30th 1959 (won by Stirling Moss in a 2.5 litre Cooper-Climax T51), or the Aintree 200 at Liverpool on April 4th 1959 (won by Jean Behra in the Ferrari Dino 246), the Aston Martin Grand Prix car made a splashy show of it when it did appear at the prestigious non-championship BRDC International Trophy race at Silverstone on May 2nd 1959.

As presented at Silverstone, the Aston Martin had an in-line 2.5 litre six-cylinder engine, which was thought to develop 260 bhp at 7,500 rpm, mounted in the front of a tubular space frame chassis. The rear suspension was a dated de Dion rear axle and the transmission was a DBR1 sportscar-derived five-speed transaxle mounted at the rear.

Although Aston Martin had experimented with double wishbones and torsion bar springs for the front suspension of the prototype, the DBR4/250 that took the grid at Silverstone had borrowed a modified Aston Martin DB4GT coil and wishbone front suspension from the sportcar parts bin. Wire wheels on Avon tires, Girling disc brakes with a ram air scoop sculpted into the left side of the bonnet and a two-tier exhaust pipe system running under the driver's elbow on the right side of the cockpit completed the picture.

Significantly, the DBR4/250 weighed in at a hefty 1265 lbs, which from the outset gave the car an unfavorable power-to-weight ratio by comparison to the Coopers (1,012 lbs.) and even the heavier Ferraris (1,232 lbs.).

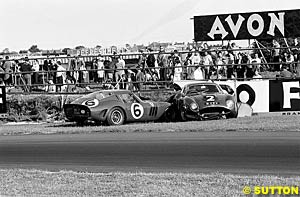

Roy Salvadori, something of a specialist at these International Trophy races, ran the race in DBR4/250, chassis 01 and teammate Carroll Shelby was entered in chassis 02. Salvadori, who started on the front row of the grid alongside the Ferrari of Tony Brooks, the Cooper-Climax of Jack Brabham and the BRM of Stirling Moss was in good form in May 1959 and in this relatively short race of only 146 miles, brought the Aston Martin home in second place, much to the relief of Reg Parnell who had suffered with the project for years. Parnell received congratulations back in the pits from rival constructor John Cooper.

Although Jack Brabham took first place in his Cooper-Climax T51, a driver/car combination destined to win the World Championship in both 1959 and 1960, Salvadori was third quickest in practice and took fastest lap in the race. Archival footage of the race shows a smiling Salvadori proudly circulating in his cool down lap in the beautifully turned out metallic silver-green Aston Martin, helmet off and in an open-collared shirt with sweater, so the crowd could see him. Once Salvadori got back to the pits, David Brown was there waiting for him and reached into the cockpit to shake his driver's hand. Later on, David Brown himself stepped forward to accept the trophy from the BRDC for second place. Those were the days.

It would turn out that when the Aston Martin mechanics got back to Feltham and tore down Salvadori's engine they would find signs that Salvadori's engine would also have blown up had the race continued much longer, suffering from the same oil circulation maladies that manifested themselves in Shelby's engine when it overreved. Doug Nye, in his History of the Grand Prix Car (1945 - 1965) at page 174, elaborates on the oil circulation shortcomings that limited the performance of the Grand Prix Aston Martins:

Sadly, that day in May 1959 at Silverstone was to be the highwater mark for the Aston Martin Grand Prix team. A month later, the DBR1/300 sports car triumphed at LeMans, which had the side effect of emboldening Aston Martin to pursue the World Sports Car Championship for 1959 , which was now within its reach, understandably diverting attention and resources away from the Grand Prix cars which could ill afford the neglect.

The official 1959 Grand Prix season began at Monaco on May 10th 1959, but Aston Martin stayed home. (Interestingly, Aston Martin had participated at the one-off Monaco Grand Prix for sportscars in 1952, when Peter Collins, Reg Parnell and Lance Macklin drove DB3s in the race.) In the absence of Aston Martin, Salvadori raced a Cooper T45-Maserati engined hybrid in the 1959 Monaco Grand Prix and is classified in sixth place though he retired with transmission problems on lap 83 of the 100 lap race. Only five cars finished the race won by Jack Brabham, all the dominant marques of the season; three Coopers and two Ferraris.

On May 31st 1959 at Zandvoort for the Dutch Grand Prix, the "David Brown Corporation" was listed as the entrant for the official first race of the Grand Prix Aston Martin. Royalty was in attendance at the seaside circuit set among the sand dunes and sea grasses. The Duke of Kent was there and was no doubt pleased to see a British car win the race, but it was BRM, not Aston Martin, that took the honors home to England that day.

The 1959 Dutch Grand Prix was the first victory for the Bourne firm that had been trying everything under the sun for a decade to win a race since the expensive and unsuccessful BRM V-16 project; it was also Swedish driver Jo Bonnier's one and only victory in a Grand Prix career that spanned 15 years, so it was a popular and historic victory all around.

Aston Martin skipped the French Grand Prix at Rheims on July 5th 1959, still savoring the June 20th 1959 victory and 1-2 finish at LeMans, which for the Aston Martin company was the kind of capstone that the BRM victory at Zandvoort had been for that team. Shelby and Salvadori had driven the winning Aston Martin DBR1/300 at LeMans and that win possibly comforted them for the disappointments they endured out on the Grand Prix circuits. At Rheims, Salvadori had no works Aston Martin to run so he drove the rear-engined Cooper-Maserati again, entered by the "High Efficiency Motors" team; the car retired on lap 20 of the 50 lap race with piston problems from that particular high efficiency motor.

On July 18th 1959, Aston Martin rejoined the tour and was back for the British Grand Prix, held at Aintree that year. It was an unusual grid: no Ferraris were present because of a strike in Italy so Tony Brooks was without a drive and made a one-off appearance for his old team, Vanwall, a team that he won for at Aintree in a shared drive with Moss for the 1957 British Grand Prix. By this time, Vanwall had actually withdrawn from Grand Prix racing, except for special appearances such as this one.

It was a wet/dry weekend at Aintree and amazingly both Aston Martin teammates showed well: Salvadori, again in DBR4/250 chassis 01 qualified second on the front row next to Jack Brabham's Cooper-Climax 251 and Carroll Shelby qualified sixth in a 24-car field in chassis 02. On race day the weather was warm and track conditions were dry.

For strategy reasons, in this 225 mile race, Reg Parnell had both cars topped up with fuel to the point that the fuel was sloshing around, coming into the cockpit and on to the backs of the drivers, leading to early and costly pitstops for both drivers from which they never recovered. But the absence of Ferrari permitted the Aston Martins to run closer to the front and Salvadori turned in a creditable performance all things considered, finishing sixth behind three Coopers and two BRMs, 1 lap down to the leaders. Carroll Shelby had his usual bad luck and retired towards the end of the 75 lap race on lap 69 with magneto problems, after running as high as seventh place behind Salvadori.

Typically, Aston Martin passed up the next race, the German Grand Prix at the fast and dangerous AVUS circuit, but turned up for the Portugese Grand Prix at Monsanto Park on August 23rd 1959. The significance of this race is that both Aston Martin teammates finished, the only time this was to occur, with Salvadori finishing in sixth place in chassis 01, 3 laps down to the leaders and Shelby in eighth place in chassis 02, both cars keeping good company with their British compatriots, the BRM P25s, throughout a race dominated by the Coopers of Stirling Moss and Masten Gregory, which finished 1-2.

Although the 1959 season ended in Sebring, Florida for the one and only time for the running of the very first U.S. Grand Prix, a state and country where many Aston Martins would be sold in the years to come, Aston Martin did not make the grid and ended its 1959 Grand Prix season at Monza for the Italian Grand Prix on September 13th 1959.

At the 1959 Monza race, during practice BRM tried out a prototype "T" car that was in essence a converted P25 called the P48, a smaller and lighter car with the 2.5 litre BRM engine located in the rear. And BRM was pressing its bets, running three and sometimes four P25s at each Grand Prix. Compare that level of commitment and experimentation with that of Aston Martin, which provided Salvadori at Monza with a warmed over and lightened version of the front-engined car with nothing on the drawing board even for 1960 that acknowledged the necessity for going to a mid-engine or rear-engine design.

A year earlier at Monza for the 1958 Italian Grand Prix, Carroll Shelby had achieved his highest career finish, placing fourth in a shared drive with fellow American Masten Gregory, running the Scuderia Centro Sud Maserati 250F. For Shelby, notwithstanding the difficult season with the Aston Martin Grand Prix car, there was much ahead in a glittering motorsports career that continues even today but this 10th place finish in the Aston Martin DBR4 was his last race for the team and, indeed, his last race as a Grand Prix driver.

Although Carroll Shelby was no longer a Grand Prix driver he would be involved again in Formula One as a constructor along with Dan Gurney in building the Eagle Gurney-Westlake V12 of the late 1960s. With the Eagle, Carroll Shelby would finally take the Grand Prix victory that eluded him so completely at Aston Martin.

Given the abysmal 1959 season, it is perhaps surprising that Aston Martin continued its Grand Prix program into the 1960 season but much had been invested and 1960 was the last season of the 2.5 litre formula to which the Aston Martins were built, so why not stay in the game. But although Lotus with its Lotus 18 and BRM with its P48 developed rear-engined cars for this last year of the 2.5 litre formula, Aston Martin, along with Ferrari, stubbornly hewed to the front-engined configuration they muddled through with for 1960. And even Ferrari experimented with a mid-engined car at the Monaco Grand Prix on May 29th 1960, when Richie Ginther ran the Ferrari 246P, which had its V6 in the rear. Ginther finished sixth in the race but the car was run only this once.

What is all the more surprising in light of all the available evidence that the front-engined design was outmoded is that Aston Martin went to the expense and trouble of building a redesigned Grand Prix car - the DBR5/250 - in readiness for the 1960 season but unexplicably still stayed with the front-engined design.

So, by mid-1960, Aston Martin stood almost alone in clinging tenaciously to the front-engined layout, joined only by the California-based American Scarab team, owned by Woolworth heir Lance Reventlow, which ran in only two Grands Prix before leaving the sport to the professionals. Like the Aston Martin, the Scarab was beautifully turned out (in the American racing colors of blue and white instead of British racing green) but so underpowered and ill-handling that not even the great Stirling Moss could get the Scarab up to qualifying speed when Moss took the Scarab out for a shakedown run when it made its debut at Monaco in 1960.

Indeed, both the Aston Martin Grand Prix car and the Scarab (which had an engine designed by Leo Goosen of Offenhauser) would probably have been in better company at the Indianapolis 500 on May 30th 1960, with an entire field of front-engined Offy roadsters than being humiliated at Monaco on May 29th 1960, as Scarab was and Aston Martin would have been had it had the temerity to even make an appearance on the twisty streets of Monte Carlo.

Uncompetitive as they were, the Scarabs technically qualified for a third Grand Prix, the 1960 Dutch Grand Prix at Zandvoort, for which fellow dinosaur Aston Martin might have also made the grid. But in the end, there was a dispute about "start money", dinosaur solidarity took hold and both of the Scarab cars and Salvadori's Aston Martin (he had come with a modified DBR4, chassis 02) were classified in the record books as DNS, Did Not Start. Why the son of Woolworth heiress Barbara Hutton and a major English sports car manufacturer with roots going back to 1914 that had just won LeMans could have allowed starting money to separate them from racing is beyond me, but I am sure it made sense to someone at the time to go all the way from California and England to Holland to race and then stand down.

Another interesting sidelight to this 1960 Dutch Grand Prix is that it was Jim Clark's very first Grand Prix in Colin Chapman's first rear-engined car, the Lotus 18. But it did not start out that way. A year earlier Clark watched from 10th place in his Lotus Elite at the 1959 LeMans race as the Aston Martin DBR1 won the race. The Scottish Border Reivers Club bought the re-built Aston Martin DBR1 that had burned in a pit fire at the Goodwood Tourist Trophy race in 1959 while in the lead and Jimmy was scheduled to and did drive the DBR1 throughout the 1960 sports car season for Border Reivers, including the 1960 LeMans race, where he took third place in the car, teamed with Roy Salvadori.

Colin Chapman had signed up Clark to run the Lotus Formula Junior and Formula 2 cars for the 1960 season but Lotus began its Grand Prix season first in Argentina and then at Monaco with Innes Ireland, Alan Stacey, John Surtees and other drivers, but not Jim Clark. Why? Because in January 1960, a few weeks before the Argentine race, chillingly in retrospect, Reg Parnell, always a good talent spotter, had already signed up Clark to replace Carroll Shelby on the Aston Martin Grand Prix team.

It is said that Parnell actually went to Berwickshire, in Scotland, to consult with Clark's parents and assure them that Clark had talent and would be in good hands at Aston Martin. As Clark's biographer Graham Gauld recounts the story in Jim Clark The Legend Lives On at pages 22-23: "Clark was signed to drive the Aston Martin Grand Prix car along with Roy Salvadori, the team leader . . . ." According to Gauld, Clark was sitting pretty no matter what happened: "[a]t this stage Clark's future in Grand Prix racing was secure, for he had been offered a full contract with Lotus should anything happen to Aston Martin."

Meanwhile, Clark himself was fascinated by the idea of driving a Grand Prix car but wary of that kind of commitment given his responsibilities back on the farm in Scotland. Says Gauld: "He was worried about how he would meet his responsibilities on the farm if he agreed to race more regularly."

Strangely, if that was Clark's problem Aston Martin in 1960 would have been the perfect Grand Prix team to join since it appeared so infrequently at the races. In any event, when it became obvious that Clark would be available at Zandvoort, Chapman offered him a spare Lotus that John Surtees could not drive because of a scheduling conflict with a motorcycle race. From that date on, Jim Clark never drove anything but a Lotus in Formula One. What a near miss, for Clark, Lotus and for Aston Martin.

At that point one new DBR5 chassis was ready, DBR5/250 chassis 01, which had a three-inch shorter wheelbase, a revised engine and had shed a few pounds; the other team car was the old DBR4/250 chassis 02, which had been converted to independent rear suspension and had also been lightened. Maurice Trintignant was recruited to replace Carroll Shelby and he drove old chassis 02 to 10th place in the International Trophy race, a car that was a far cry from the Cooper T51s he spent 1960 hopping in and out of for privateers Rob Walker and Scuderia Centro Sud. But if there was ever a driver who could bring the bulky and temperamental car home in one piece it was Trintignant.

The Last Hurrah for the Aston Martin Grand Prix cars also came at Silverstone for the British Grand Prix on July 16th 1960, where DBR5/250 chassis 01 was entered for Roy Salvadori and Maurice Trintignant had the modified DBR4/250 chassis 02. Salvadori qualified reasonably well, 13th of 24 cars on the grid, all but a few rear-engined by now, but he went out on lap 17 of the 77 race with steering trouble.

Typically, Trintignant stayed the course and finished 11th, after qualifying only 21st. As a result, Trintignant has the distinction of being the only Aston Martin Grand Prix driver to complete all the races he started!

David Brown, obviously a patient man, had seen enough and withdrew Aston Martin from the balance of the 1960 Grand Prix season. What became of the six Aston Martin Grand Prix cars? The last generation of the Aston Grand Prix car, the two so-called DBR5s built for 1960 - chassis 01 and 02 (which was never actually completed) - were ultimately scrapped along with the chassis originally known as DBR4/250 chassis 02, which tended to be Carroll Shelby's 1959 car, but was later converted to independent rear suspension for the 1960 season. So all the later cars are gone.

The other three earlier cars survive in various forms. Two of the cars were rejuvenated by installation of the 3-litre RB6/300 Aston Martin sports car engine and were sold to buyers in Australia. One of those cars, the 1959 spare car chassis DBR4/250 chassis 04, was brought back to the Aston Martin factory at Feltham in 1961 to soup it up a bit to produce 296 bhp at 6700 rpm so it could race in the short-lived British InterContinental Formula races before going back to Australia. In this form, the car has its exhaust pipes low down on the left side of the car and the ram air scoop on the right hand side of the bonnet.

By the late 1960s, all three surviving cars had returned to collectors in England and the two 3 litre cars have appeared together in historic racing. One of the cars has been restored by Tom Wheatcroft and can be seen by the public in his Grand Prix Collection, which is located adjacent to the Donington racetrack near Derby, England. The brochure describes the car as follows: "This is the first 1959 chassis with David Brown gear box. Driven by Salvadori, it came 2nd in the 1959 Silverstone non-championship race . . ."

Ironically, nearby in the same Donington Collection sits a Scarab: those front-engined dinosaurs may not have been fast but they surely are Survivors!

Turning to modern Formula One and to developments in motorsports generally that exhalt product "branding" above all else, is it possible that Aston Martin, 100% owned by Ford since 1994, would ever return to Formula One or would ever want to? While at first blush it may seem far fetched, it should be remembered that in the heyday of Stewart Grand Prix, before it became Jaguar, much was made in Aston Martin's press releases of the fact that the development of the Vantage, Aston Martin's Supercar, reflected "the wealth of experience [Ford Advanced Vehicle Technology and Cosworth Engineering] has gained from participation in Formula One Grand Prix . . . benefitting from Ford AVT's direct involvement with Stewart Ford Formula One team and Bridgestone tires." To quote from one of those releases:

Doesn't this sound like Everyman's Formula One car to you?

It is a curiosity that Ford Motor Company now owns so many of the jewels in the crown, the evocative brand names that sell cars. Indeed, the current James Bond movie, "Die Another Day", is in some ways one long product placement advertisement that showcases Ford products. The silver Aston Martin Vanquish that is almost as easy on the eyes as the latest Bond girl, Halle Berry, is a Ford Product, as is the very un-British metallic lime-green Jaguar XKR that Bond's Korean adversary, Zao, drives in the climatic scene at the end of the movie.

Mid-movie, Halle Berry pulls up to a black-tie party at night in a red Thunderbird with a coral-colored hardtop sporting a "porthole" window motif, 700 (naturally) of which are to be sold to the public as the "2003 Limited Edition 007 Thunderbird." And when Pierce Brosnan is chasing down the villains in Cuba, he magically ends up driving a fabulous 1957 Ford Fairlane convertible. In the waterfront scene supposedly set in Cuba, another Ford product, a 1953 Mercury is center stage.

It is no secret that Ford is unhappy with Jaguar's failure to become a force in Formula One, the firing of Niki Lauda and the selling of Ford Cosworth engines to Jordan being the most visible signs that Detroit has put its Jaguar cat on a short leash.

Meanwhile, over at Ferrari, Luca di Montezmolo has announced that their "other" in-house brand, Maserati (which has been a subsidiary of Ferrari since 1997), has become his special project, rebuilding the brand to make it a better contributor to Ferrari's profits being his latest mission, possibly by returning Maserati to sports car racing.

Aston Martin plays a similar role at Ford as a brand name just begging to be enhanced and projected but Aston Martin's rebuilding period is already behind it and it can only go up from here. Aston Martin has never lost its reputation for the quality of its manufacturing process, which even today means that each Aston Martin is hand built in a ramshackle set of red brick buildings in Newport Pagnell, where panel beaters bend aluminum into curvaceous body shells with special hammers and sanding tools and engine blocks are completed with the mark of the chief engine builder stamped on the bottom.

Aston Martin has a racing history that goes back to the 1920s and yet also a modernity and crispness about the products it produces that may well make Aston Martin the next brand Ford chooses to make more visible, to capitalize on Ford's hefty investment, or to build its marketability and dispose of the company to a more congenial owner.

In February 2001, the sophisticated and technologically advanced V12 Vanquish was unveiled at the Geneva auto show and now in 2002 the James Bond film can only help continue the mystique of the Aston Martin name that the early James Bond films began.

In November 2001, it was announced that the 5,000th DB7 Vantage Coupe was completed, a production run that exceeds the combined total of the DB5 and DB6 models. By comparison, Ferrari sells approximately 4,300 production cars each year, 30% of which are sold in the United States.

Can it be long before someone at Ford wakes up and discovers the potential of Aston Martin. And when they do, will Formula One be the manifestation of that recognition, or will Ford follow in the footsteps of Volkswagen and re-introduce Aston Martin into racing at the sports car level, as Volkswagen has done with Audi and Bentley and as may be in the works for Maserati?

I know it is hoping against hope considering what happened the first time around but I would love to see Aston Martin and those wonderful craftsmen at Newport Pagnell get Ford's backing to take on Ferrari one more time, chassis number "007" of course, this time presumably with the engine located behind the driver! To paraphrase James Bond in "Die Another Day": "don't chase dreams, live them."

We are accustomed to hearing and believing that Formula One is the pinnacle of motorsports but for sports car manufacturer Aston Martin in the late 1950s it was an afterthought, a secondary challenge, something to be gotten to in due time but certainly not as important as, for example, winning the LeMans 24-Hour Endurance Race.

While watching Pierce Brosnan, the latest MI6 Agent 007, put the sleek, silver 2002 Aston Martin V12 Vanquish through its paces in the latest James Bond film "Die Another Day", I was reminded of the story of the Aston Martin Grand Prix cars which, in its own way shows what a tough game for constructors Formula One has always been and continues to be, even among those who, like Aston Martin, have the credentials and wherewithal to succeed. Ask Renault, Jaguar, Honda and now Toyota.

While watching Pierce Brosnan, the latest MI6 Agent 007, put the sleek, silver 2002 Aston Martin V12 Vanquish through its paces in the latest James Bond film "Die Another Day", I was reminded of the story of the Aston Martin Grand Prix cars which, in its own way shows what a tough game for constructors Formula One has always been and continues to be, even among those who, like Aston Martin, have the credentials and wherewithal to succeed. Ask Renault, Jaguar, Honda and now Toyota.

The timeline illustrates in retrospect how ill-starred the whole venture was for Aston Martin. On January 19th 1958, Stirling Moss set the Grand Prix world on its ear by scoring the first win for a rear-engined car (that is since September 1939 in Belgrade when Nuvolari in the rear-engined Auto-Union won the last race before the war), when he won the Argentine Grand Prix at Buenos Aires in Rob Walker's light and maneuverable Cooper T43 with its 1.96 litre Climax engine in the rear.

The timeline illustrates in retrospect how ill-starred the whole venture was for Aston Martin. On January 19th 1958, Stirling Moss set the Grand Prix world on its ear by scoring the first win for a rear-engined car (that is since September 1939 in Belgrade when Nuvolari in the rear-engined Auto-Union won the last race before the war), when he won the Argentine Grand Prix at Buenos Aires in Rob Walker's light and maneuverable Cooper T43 with its 1.96 litre Climax engine in the rear.

This same DB3S finished second at LeMans in 1955. So the deferral of the Grand Prix program in 1958 had not borne fruit for Aston Martin at LeMans and had only made the DBR4/250 Grand Prix car even more obsolescent than it already was when it was tested in December 1957/January 1958. Even then, the technology of Formula One did not stand still for too long.

This same DB3S finished second at LeMans in 1955. So the deferral of the Grand Prix program in 1958 had not borne fruit for Aston Martin at LeMans and had only made the DBR4/250 Grand Prix car even more obsolescent than it already was when it was tested in December 1957/January 1958. Even then, the technology of Formula One did not stand still for too long.

Carroll Shelby, who, in the space of the next eight years would create the Shelby Cobra, help Ford win LeMans with the GT40 and form All American Racers with Dan Gurney, was 36 years old and at this point in his career a relatively new driver, having driven in only four Grands Prix, campaigning a Maserati 250F in 1958. But he drove for Aston Martin in sports cars and signed on as Salvadori's teammate in the Aston Martin Grand Prix car for 1959. Shelby had a more frustrating experience than Salvadori in the International Trophy race, and one that would turn out to be more representative of Aston Martin's Grand Prix effort. Shelby finished in sixth place, two laps down, having blown up the engine when the main bearing of the engine failed due to the loss of fifth gear and consequential overreving of the engine. Not a good day for the Aston Martin engine/gearbox parts bin.

Carroll Shelby, who, in the space of the next eight years would create the Shelby Cobra, help Ford win LeMans with the GT40 and form All American Racers with Dan Gurney, was 36 years old and at this point in his career a relatively new driver, having driven in only four Grands Prix, campaigning a Maserati 250F in 1958. But he drove for Aston Martin in sports cars and signed on as Salvadori's teammate in the Aston Martin Grand Prix car for 1959. Shelby had a more frustrating experience than Salvadori in the International Trophy race, and one that would turn out to be more representative of Aston Martin's Grand Prix effort. Shelby finished in sixth place, two laps down, having blown up the engine when the main bearing of the engine failed due to the loss of fifth gear and consequential overreving of the engine. Not a good day for the Aston Martin engine/gearbox parts bin.

"The DBR4/250s' engine bearings seemed highly suspect. In the longer GPs a [rev] limit of just 7000 rpm was applied to stand any chance of finishing. The reason was identified too late that year: the crankshaft oilway drillings at [Top Dead Center] were apparently wrongly sited. They might work fine in sports car racing at 6500 rpm, but at 'seven-five' in Formula 1 oil supply was sorely restricted. The Aston engines also seldom seemed adequately carburetted."

For the Aston Martin team, the race was a painful initiation as the cars finished last and next to last. Shelby qualified 10th and Salvadori 13th out of 15 cars. After three laps, Salvadori was out with overheating problems, abandoned the car out on the track and returned to the pits on foot; Shelby soon joined him there after 25 laps of the 75 lap race, also with engine problems. It is remarkable to consider that the downsized Aston Martin Grand Prix engine gave the team such fits when the 3.0 litre Aston Martin sports car engine from which it was cloned could drone on for 24 hours and thousands of miles at LeMans.

For the Aston Martin team, the race was a painful initiation as the cars finished last and next to last. Shelby qualified 10th and Salvadori 13th out of 15 cars. After three laps, Salvadori was out with overheating problems, abandoned the car out on the track and returned to the pits on foot; Shelby soon joined him there after 25 laps of the 75 lap race, also with engine problems. It is remarkable to consider that the downsized Aston Martin Grand Prix engine gave the team such fits when the 3.0 litre Aston Martin sports car engine from which it was cloned could drone on for 24 hours and thousands of miles at LeMans.

In a 21-car field, Shelby's chassis 02 finished its second race of the season in tenth place, 2 laps down to the leaders. Salvadori had the latest lightened version of the car DBR4/250, chassis 03, but retired with engine problems on lap 44 of the 72 lap race after running as high as seventh place. There was a fourth chassis, DBR4/250 chassis 04, back at the Feltham factory that was not raced. It is interesting to contrast Aston Martin's reaction to the now-undeniable success of the rear engine cars with that of BRM.

In a 21-car field, Shelby's chassis 02 finished its second race of the season in tenth place, 2 laps down to the leaders. Salvadori had the latest lightened version of the car DBR4/250, chassis 03, but retired with engine problems on lap 44 of the 72 lap race after running as high as seventh place. There was a fourth chassis, DBR4/250 chassis 04, back at the Feltham factory that was not raced. It is interesting to contrast Aston Martin's reaction to the now-undeniable success of the rear engine cars with that of BRM.

The Scarab did manage as its highwater mark to finish 10th in the US Grand Prix at Riverside, California, the team's home track, in a shortened, lightened and otherwise modified Scarab, albeit five laps down to Stirling Moss in his Lotus 18. Interestingly, it was en route to this 1960 Riverside race (which was held on November 20th 1960), that John Cooper and Jack Brabham took the Cooper-Climax T53 to Indianapolis for an historic exploratory run on October 5th 1960 that sowed the seeds of the rear-engined revolution at Indianapolis.

The Scarab did manage as its highwater mark to finish 10th in the US Grand Prix at Riverside, California, the team's home track, in a shortened, lightened and otherwise modified Scarab, albeit five laps down to Stirling Moss in his Lotus 18. Interestingly, it was en route to this 1960 Riverside race (which was held on November 20th 1960), that John Cooper and Jack Brabham took the Cooper-Climax T53 to Indianapolis for an historic exploratory run on October 5th 1960 that sowed the seeds of the rear-engined revolution at Indianapolis.

Aston Martin having voluntarily passed up the 1960 Dutch Grand Prix, confined itself to one official appearance in the 1960 season, predictably the British Grand Prix at Silverstone and one other participation in the non-championship BRDC International Trophy race in May 1960, also at Silverstone.

Aston Martin having voluntarily passed up the 1960 Dutch Grand Prix, confined itself to one official appearance in the 1960 season, predictably the British Grand Prix at Silverstone and one other participation in the non-championship BRDC International Trophy race in May 1960, also at Silverstone.

"With its body and chassis constructed entirely from aluminum and carbon fibre Project Vantage provides all the engineering efficiencies, structural integrity, torsional rigidity and occupant protection of a modern Formula 1 car. In addition, the central venturi incorporated in the underbody creates positive down force that contributes to its directional stability."

Please Contact Us for permission to republish this or any other material from Atlas F1.

|

Volume 8, Issue 49

Aston Martin's GP Cars

Rear View Mirror

Bookworm Critique

Elsewhere in Racing

The Weekly Grapevine

> Homepage |