Atlas F1 Special Columnist

Ann Bradshaw was Williams's press officer on that dark weekend when the team had lost their newly signed star driver. She recounts the events of that weekend and how the Williams team handled the tragedy

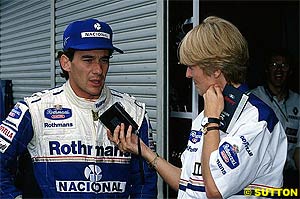

WilliamsF1 was on a roll as it had won both the Drivers' and Manufacturers' Championships in 1992 and 1993. The fact that both Nigel Mansell and Alain Prost had subsequently left was not a big drama as at last the man Frank wanted was in the Rothmans liveried Williams-Renault. The Williams-Renault had not been the fastest car in winter testing, but the team was confident of success as a certain amount of sand-bagging had taken place.

We went to Sao Paulo in Brazil, where we were treated like royalty, and then to Aida in Japan. On the way back from Japan I remember sitting next to engine builder Brian Hart and chatting about what a disaster the first two races had been for Ayrton. Pole in both but nothing to show for it as he had crashed out of both. Damon Hill had picked up second place in Brazil, but this was not how we had envisaged the season starting.

Suddenly the familiar figure of Ayrton came along the gangway. He had left his first class seat and had suddenly arrived in economy as he wanted to have a chat with his old mate Brian. It was a Hart engine that had powered his Toleman in 1984 and the two men had formed a friendship then that had remained strong. The flight was full, so Ayrton sat on the floor and spent the next half an hour talking about cars and planes.

He was not going to have some time off as he had planned; he was going straight to the WilliamsF1 factory in Didcot to work with the team to try and sort out what had gone wrong. Although he had claimed poles and had led for 21 laps in Brazil, the car was not how he wanted it, and so the solution was to be with the engineers to work out what the problem was.

Saturday then came, and things went from bad to worse with the death of Roland Ratzenberger in second qualifying. We were all shocked, and any desire to go out and set fast times soon left the drivers. Ayrton did not go out. As things turned out his time from the Friday session was good enough for pole, but even if Michael Schumacher had beaten him I am certain Ayrton would have stayed in the garage.

I put a press release out on behalf of the team that paid tribute to Roland and his team, Simtek, which would never really recover from this blow. I didn't mention the fact my boys were first and fourth on the grid; it just wasn't important.

I cannot comment on people who suggest Ayrton did not want to race and somehow had a premonition that Sunday would end in death for him. We carried on as usual. The warm up was trouble free and we all breathed a sigh of relief hoping that the race would be the same, and that we could go home and put the dramas of the 29th and 30th April behind us. Sadly our prayers were not answered.

I still find it difficult to remember at what point I realised we didn't just have a racing accident on our hands from which our driver would walk into the back of the garage to explain what had gone wrong. I have spent many a race at the back of the garage waiting for the driver to come down the paddock pursued by a gaggle of journalists wanting to know what had happened. I knew by the way the driver could not be seen moving in the car and the way the medical staff were kneeling by the car that this was different.

I think I then went onto autopilot. The race was stopped. I grabbed Damon's umbrella and went to stand over him where the cars had been stopped. There was not much I could tell him, and in many ways this was best as he still had a race to run.

Once back in the paddock I had to turn my attention to what was happening with Ayrton. Martin Whitaker was the FIA Media Delegate, and he was able to keep me up to date with the latest situation. Ayrton had been taken to the hospital in Bologna and we had to await reports from the doctors there and the F1's own medical supremo, Professor Sid Watkins.

Reports from the hospital were suggesting this was serious, and I knew that we all had to stay calm and just report the facts as they were given to us. In such circumstances there is no room for repeating anything but hard facts, and emotions must be kept under control.

The race finished, and Damon was sixth. There was nothing I could do for Ayrton so Damon then became my priority. I remember going to parc ferme to collect him. He wanted to know how Ayrton was. There was not much I could tell him, but this was telling in itself.

Luckily at that race I had Jane Gorard with me. Jane was the factory based Media Manager, and so didn't usually attend the races. Thank goodness she was there this time. We worked as a team and knew that we had to be the public face for WilliamsF1. I shall always remember Frank calling us into the motorhome and telling us that if we thought we were going to cry then we should put our sunglasses on. We both spent the rest of the day wearing them.

There was then the lull before the storm. The stunned mechanics were packing up and doing the usual Sunday night rush to the airport. Frank had gone to the hospital in Bologna. I had decided to change my plans as I felt so much would happen the next day that the team would need me in Didcot. There was nothing left for me to do at the circuit, and so my friend Louise Goodman drove me to the airport to join the rest of the team on what proved to be a very sad journey home.

I still had no news on Ayrton's condition apart from it was serious. As I walked out of the paddock I remember Guardian journalist Alan Henry coming up to me and saying “I'm so sorry." For the first time that day I cried.

As I got to the airport I received the call I was dreading. Ayrton had died. I knew, but no one else there did. I managed to organise a room into which I got the team. I brought in beers for the boys and then I had to stand in front of them and tell them we had lost Ayrton.

The plane journey to Gatwick was a sombre affair. Then as we came in to land the captain sent a message to us that the airport was besieged by the press. We had the entire team and Damon on the flight. The last thing we wanted was press trying to talk to the mechanics who worked on Ayrton's car. Surely they would have been questioning themselves about what they did as they prepared it for the race, and they did not need intrusive questions.

With the help of Jane and the officials at Gatwick we managed to get Damon taken out by the back door, and then as the baggage was being collected I went out to do a deal with the press. I would talk to them. I would answer all the questions but it was on the understanding they let the ‘boys' leave unhindered. Members of the press get a bad reputation for being intrusive, but in this case I have nothing but respect for them. To a man they agreed and stood back at a respectful distance as the team left.

The following week was a blur. Frank went to Brazil for the funeral, and we went to a service at the Brazilian church in London where the gates of the factory were festooned with flowers and messages from fans and Brazilians living in the UK. They were all shocked, but the amazing thing was all the messages we had were supportive.

I was worried they would blame us for what happened to their hero, but there was none of that. I made some good friends in the following days when Jane and I went out to meet them. We accepted flowers on behalf of the team and exchanged hugs with people who, like us, felt they had lost a good friend.

Eventually Ayrton was laid to rest on a hill overlooking his beloved Sao Paulo. Millions of people followed his funeral procession, and Brazil had lost someone who represented what magic could come out of a country that has so much poverty.

Sadly the whole affair was not laid to rest. In fact I still see regular articles suggesting the investigation will be re-opened. For the team, no blame was laid at its door, but I am sure for all of those working at WilliamsF1 in those days the question will always be there – is there anything we could have done to prevent this?

Over the past ten years I have read many different versions of what happened on May 1st 1994 in Imola. People who were not even there have earned money from their perspective on the whole ghastly weekend. I don't blame them for identifying a market for what I feel sometimes have been morbid tomes, but I do feel the key people who were there at the centre of this have quite rightly kept their thoughts and feelings to themselves.

Apart from Ayrton Senna's family, Frank Williams was perhaps the person most affected by what happened. He had harboured a dream for many years and that was to have Ayrton Senna race a Williams. He was the first man to have put the young Brazilian in an F1 car and sadly, as it turned out, the last. He had always had a strong friendship with Ayrton. They shared a love of aeroplanes and spent many hours discussing these. For me his death on that day was shocking and something I had to live through in a professional way, but it was the strength that Frank showed when he became the centre of the world's media that helped me get through the day and those that followed.

Apart from Ayrton Senna's family, Frank Williams was perhaps the person most affected by what happened. He had harboured a dream for many years and that was to have Ayrton Senna race a Williams. He was the first man to have put the young Brazilian in an F1 car and sadly, as it turned out, the last. He had always had a strong friendship with Ayrton. They shared a love of aeroplanes and spent many hours discussing these. For me his death on that day was shocking and something I had to live through in a professional way, but it was the strength that Frank showed when he became the centre of the world's media that helped me get through the day and those that followed.

Two weeks later, and after much work, Ayrton and the team arrived in Imola. The weekend was going to plan until his good friend and fellow Paulista, Rubens Barrichello, had a big accident on the Friday in his Jordan. It looked horrendous, and Ayrton was the first driver to rush to check on Rubens. Thankfully, as we all held our breath, the news came out that Rubens was okay, even though he was subsequently not allowed to race.

Two weeks later, and after much work, Ayrton and the team arrived in Imola. The weekend was going to plan until his good friend and fellow Paulista, Rubens Barrichello, had a big accident on the Friday in his Jordan. It looked horrendous, and Ayrton was the first driver to rush to check on Rubens. Thankfully, as we all held our breath, the news came out that Rubens was okay, even though he was subsequently not allowed to race.

The team was trying to find out what had happened. We had one driver still in his car at the side of the track and another about to set off again to finish a race. They had to be sure that Damon's car was not in any danger of having a problem. Engineers checked it and once they were sure it would be okay he was allowed to take the re-start.

The team was trying to find out what had happened. We had one driver still in his car at the side of the track and another about to set off again to finish a race. They had to be sure that Damon's car was not in any danger of having a problem. Engineers checked it and once they were sure it would be okay he was allowed to take the re-start.

|

Contact the Author Contact the Editor |

Please Contact Us for permission to republish this or any other material from Atlas F1.

|

Volume 10, Issue 15

Special Issue

View from the Imola Paddock

The Feud with Prost

A Lesson in Safety

From Fangio to Schumacher

The Dark Side of the Man

Memories of May

Keith Sutton: The Senna Collection

Columns

Elsewhere in Racing

> Homepage |