Atlas F1 GP Correspondent

The 1994 San Marino GP was the beginning of a hectic and traumatic month for the F1 press corps. Timothy Collings was there and will never forget that fateful time

It was a year that ended when Damon Hill's ambitions were literally smashed to oblivion by a collision in Adelaide, when Paris court hearings ruled on various kinds of evasion of the rule book - from fuel filter tampering to black flag fiascos - and when a series of drivers suffered enormous accidents. Some were killed. Some survived.

In essence, it was the month of May that encapsulated the best and the worst of it all. More than that, the weekend of May 1st - that May Day Sunday that took Senna away - left the deepest cut on the memory. Two weeks later, on the streets of Monte Carlo, at a solemn Monaco Grand Prix splashed in tears and deep emotional recollections, the front of the grid was an empty-spaced tribute to the great Brazilian and the aspiring Austrian, but the shock of seeing Karl Wendlinger smash into the barriers at the exit of the tunnel, survive, hang on in a coma, day after day, to emerge, eventually, was another almost-unbearable assault on the nervous system.

And there were other accidents. Other journeys. Other experiences. That month of May 1994 was crowded in time. There was no breathing space. It was relentless. Few of us could stop and pause for air, or thought, or reason. Each catastrophe seemed to be followed almost immediately by another. The ringing of telephones, for news, for stories, for information, or to break news of another happening that intensified the horrors, was the soundtrack to a tragic and tiring daily grind in feeding a ravenous media machine and, at the same time, attempting to maintain a normal human perspective and stay in touch with personal reality at home. Few of the phone calls were brief. Each was another exhausting experience that dragged energy from weary limbs and a tired mind, left the heart to sink and fight back in the aftermath.

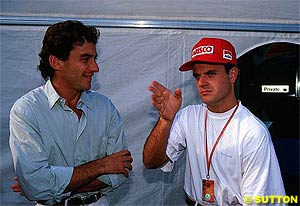

Will I ever forget it? I don't think so. That San Marino Grand Prix of 1994 began with eerie foreboding - and ended in desperate tears and tragedy. A pall of sinister intuition pervaded the atmosphere from Thursday's arrival, when I interviewed Ayrton Senna for the last time as he sat outside the Williams team motorhome and cracked jokes, to Monday's departure, when I visited Tamburello and saw the stains left on the asphalt of the Enzo e Dino Ferrari circuit at the scene of his death. The blood was on the track and the flowers were hanging in the trees, shrubs and fencing nearby.

Imola supplied many other black and heart-wrenching moments, and left a scar on the collective conscience of Formula One that year. The trip to central Italy, to the circuit set in the rolling vineyards of Emilia Romagna, was always a prospect that signaled optimism and springtime. In many ways, it still is.

Then, it was the first race in Europe, as it is this season. It often coincided with warm weather and welcome sunshine and it usually delivered a lively crop of stories, paddock parties and late-night dinners in the local ristorante, alive with joyful chatter and amusement. But in 1994, for reasons unknown and unfathomable, it was all very different. That year, in one long weekend of escalating horror, the joy and the life drained away.

On Thursday, in the overcrowded, but friendly, paddock, Senna arrived for his pre-race publicity work with a frown. Newly-transferred to Williams from McLaren, he had endured an unhappy start to the year with his new team. He was angry, in particular, at what he perceived to be the irregular advantages gained by his new young rival Michael Schumacher, then rising to fame with Benetton.

In his motor home on that Thursday, I recall Senna smiling with the BBC's veteran commentator Murray Walker about how he, Walker, had changed his pronunciation of the driver's first name. They laughed. It may have been the last time he laughed aloud. He was invaded by doubts, fighting feelings of uncertainty, attacked by concerns about the level nature of the mechanical and technical playing field on which he was competing against the new kid on the block, the boy from Kerpen.

That evening, at a sponsors' reception hosted by Porsche, an Australian reporter working for an American newspaper won a car in a raffle. It was a nice car that every diner sitting to eat in a sprawling country restaurant, miles from anywhere in the dark fields of central Italy, had wanted to win, own and drive. Nearly all of the media corps groaned in disappointment. The reporter, perhaps sensing a curious meaning attached to his prize, later sold the car.

That media and sponsors' dinner, a vast affair of virtually-interminable length, dish after dish following one another, had been delayed by poor planning, overcrowding and chaos, and most went home early, hungry or in low spirits. It was difficult to discern at the time, but something was amiss from the start. Only rarely can anyone leave an Italian restaurant with anything other then a smile.

On Friday, in an accident that staggered everyone, the young Brazilian Rubens Barrichello crashed his Jordan so heavily and comprehensively it was unlikely he would escape alive, and almost certainly not without serious injury. Miraculously, he did. And when he awoke from being knocked unconscious, and after the most important and priceless man in Formula One, professor Sid Watkins, had saved his life, leaving him only with a broken nose, the first person he saw was Senna.

Those tears had hardly dried away when other strange happenings upset the normal rhythm of the Imola weekend. Senna's unease was manifest and apparent. He talked to his closest friends and advisors. They whispered to others. No-one knew what lay ahead.

On Saturday, he was shaken to his boots again when, during second qualifying (the first qualifying session was held on Friday afternoon), the young Austrian driver, Roland Ratzenberger, lost control of his Simtek car on the fast run up to the Tosa hairpin. A car failure left him helpless as his monocoque was torn open on impact with the barriers. It was a massive and horrible accident. There was a clear hole through the safety cell. He was killed. The horror began.

There had not been a fatality in Formula One for so long that few among the army of journalists knew how to react, and few in the paddock could help. The session halted.

Ratzenberger was a man of hope and laughter. He may not have been a sublime talent who shook the world, but he was a man of endeavour and ambition, a driver who loved his job, who had toiled to reach Formula One and take the opportunity and, away from the track, he was one of the most humorous, personable and likeable men of all.

The tears that flowed as his body was lifted away, as helicopters whined overhead, as the track announcers babbled on and the radio and television teams scrambled for scraps of emotional intrusion, pieces of grief, others' pain and agony, were authentic. Friends hugged and stood behind the trucks in crazy silhouettes of physical sympathy.

Drivers, the sport's bold gladiators, stood around in clusters. Few knew what to do. Senna, his pride activated, his adrenalin running, took action. As he did on Friday, he wanted to see things for himself. He went out to inspect the scene of the accident and to visit the circuit medical centre. This time, there was nothing even 'the Prof' could do.

That qualifying resumed was in itself a small, albeit little used, miracle; Senna's time from Friday was good enough to claim his last ever pole, ahead of Schumacher. As Ratzenberger's body was taken for him to be declared dead away from neutral non-racing ground, the racers raced on.

In the press room the noise came from telephones, shouting reporters swapping items of information, the relays of media sound-bites broadcast from below into the cyberspace of audiences waiting for sensation from afar to stimulate their minds and days to life. Word counts for the Sunday newspapers, normally in the region of 400 to 600 words for an account of the day's qualifying action, were doubled and additional stories, requests for reaction and descriptions of the inner feelings were made. It was a strange Saturday that went from unusual to ugly.

Long talks, pregnant with personal feelings, went on into the small hours while phones continued to ring, with calls from London's Monday newspapers asking for additional features explaining why, and how, death had returned to haunt the sport of playboys and technicians. One for me, from the London Daily Mirror, asked for a double-page spread on the return of death to the sport and required an interview with a major figure associated with the sport and its history. The call came through at 02:45 am and lasted half an hour.

The man, the sports editor in England, could not sleep. He was planning his pages for the following day in the circulation battle that existed between his popular tabloid and Britain's most popular of the time, the Sun. Like me, the Sun reporter also fielded night time calls requesting additional work. Like me, he too was tired.

And then came Sunday, May 1st 1994. After an early start, the interview with Niki Lauda on safety in F1, delivery of work, and a long morning of unofficial inquests, I joined the throng that followed Senna's movements as, stern-faced, pensive and brooding, he convinced himself to race.

Senna climbed into his car, took his place on pole position, drove away and, after the early intervention of the Safety Car for a multiple collision at the start, he died. Senna was killed on lap seven. He led from the lights, ahead of Schumacher, ran behind the Safety Car for four laps, held the young German at bay on his sixth, when his car bounced across the bumps at Tamburello and, soon after starting his seventh, ploughed off the circuit and into the wall. Just 12.8 seconds into the lap, at 190 mph, his car hit the concrete, a steel suspension arm from the front right wheel snapped away and punctured his yellow helmet and his right temple.

Italian television cameras broadcast it all. It was a public death. The race was red-flagged to a halt, then re-started and Schumacher won. None of the drivers were told that Senna was dead until it was all over. In the media centre, there was uproar.

One woman reporter, who had been writing a book with the Brazilian and had been so close to him it was almost a relationship of deeper than usual closeness between reporter and sportsman, ran amok in grief, crying and screaming. A veteran French journalist, a man who had seen it all before, crumpled over his desk and wept. Announcements from the public system were contradicted by radio reports and shouting Italian journalists with contacts in the local hospital, to which Senna's body was transported.

A day that had started in fatigued shock had turned into a bloody nightmare. News desks called to ask for advance obituaries while the race continued. I was required to 'write' 1000 words or more on the life of Senna (a task that I performed in the time-honoured fashion of all experienced reporters by ad-libbing and dictating the whole item) while, at the same time, trying to take notes of the continuing drama, and the race that re-started.

Again, and again, and again, the phones were ringing. 'Features, too, please; and profiles and reactions; and 'think-pieces' that explain all of this' as well as the usual, well, longer-than-usual race reports. And more.

It was a stream of demands that kept professional instincts intact as the F1 show threatened to run off the rails, as paddock cognoscenti collapsed, as Bernie Ecclestone warded off the questions and Imola officials staggered under the weight of their responsibilities. It was hard for Ecclestone. His natural sense of dry and often black humour was inappropriate on the day and he was pressed hard by Senna's family and Brazilian media. There was little or no information that could be trusted. The FIA president Max Mosley was absent also, watching the horror unfold on television at his country home in England.

Bizarrely, it was reported, a few days later in a London tabloid that Ecclestone had left his private office at Imola, at that moment, stood in his garden and wept. Such inaccuracies were to spawn further and greater untruths in the coming days as rumours and counter-rumours swirled around the biggest Formula One story of modern times.

By dusk, that Sunday, the worst was known and confirmed, the racing was over, keyboards were clattering, helicopters hanging, cars queuing to leave amid the rancorous beginnings of arguments and inquests. An extraordinary air hung over a paddock that had emptied rapidly and silently. Or as rapidly and silently as was possible. Circuit officials were already being questioned; defensive statements being drawn up. The first shock was replaced by a need to apportion blame.

We, who had stayed at the plain little Villa Fiorita hotel in Riolo Terme all those years in succession, a place hosted by two generous middle-aged Italian sisters, finally trudged back there, over the mountain, beyond three or four the following morning. London and its hungry news desks had been fed. The day had gone. Night had fallen. White shell-shocked reporters' faces betrayed exhaustion as they trudged into the hotel and sat down.

On Monday, May 2nd, after visiting Tamburello in the morning, writing reaction and descriptive articles, we traveled to Bologna, to the airport. There we sat with Professor Sid Watkins again. He talked of his experience, explained what had happened. He was at Senna's side out there as he died. Then the flight home to London and a news conference with Mosley at his London offices; a small building crowded with heat and light and tired bodies. Rapid questions were met by prepared answers. The men who had been in Imola all weekend had experienced something Mosley could not fathom.

The reaction in Britain and Europe was surprising. As Mosley talked of the obvious dangers, the inevitability of death, it became clear his tone was out of synch with a new reality, a new political correctness that demanded more and wanted answers. Senna's death had to be explained. It could not be swept away in a series of smooth answers.

Mosley soon realised this and within days another major news conference was held in Paris. Why was there a wall - a concrete wall - on the outside of Tamburello? Why not tyres and tyres and better gravel and slower run-off and more distance and greater safety and slower cars and better protection for drivers? The unofficial inquests began.

At home, still the phone rang. Every day. More and more stories please. Even the following weekend, the pressure continued. Unrelenting demands for copy, fresh angles and new interviews were wanted. Meanwhile, in Sao Paulo, Brazil came to a halt to bury Senna in Morumbi as the world watched, as Ecclestone was made aware he was not wanted by the family, as Alain Prost, his oldest and greatest rival, wept among the pallbearers. And then came the previews and preparations for Monaco, a race that demanded more than most as a natural part of its status as the most glamorous event on the calendar.

Curiously, I flew that year from Stansted to Nice with Air UK. I sat at the front of the plane and my immediate neighbour, in the adjoining seat, was a young and tearful Latin American. He was a deeply-upset fan of the great Brazilian Senna. Indeed, he had been there at the funeral. He had taken part. He was called Rubens Barrichello.

He emptied his heart. It was private, moving and sad. He was not in a good state to race. His emotions were in charge of his body and his mind. But he was to be embraced by Eddie Jordan and nursed through a tortuous weekend. It was a horrible Monaco Grand Prix. And everyone was so glad to see the back of it and the end of May in 1994.

It was the blackest weekend of the darkest month in a season of death, tragedy, cheating and controversy. No one will forget Imola, or the San Marino Grand Prix of 1994; none of us who went through it will forget the month of May that went with it; and none of us will forget the exhaustion, physical and mental, that went with covering Formula One through that whole extraordinary season.

It was the year of working dangerously in a sport that had slapped its own back for more than a decade, preening itself on its own safety record. It was the year that saw Ayrton Senna pass away, Roland Ratzenberger die with him in the same weekend of grim horror and, in a trail of unpleasant incidents and arguments, Michael Schumacher emerge as a new World Champion for Benetton-Ford.

It was the year of working dangerously in a sport that had slapped its own back for more than a decade, preening itself on its own safety record. It was the year that saw Ayrton Senna pass away, Roland Ratzenberger die with him in the same weekend of grim horror and, in a trail of unpleasant incidents and arguments, Michael Schumacher emerge as a new World Champion for Benetton-Ford.

But this time, if it is to be the last, it will be a bitter-sweet experience; the memories will flood back, the wine will taste better as it rolls across the tongue, the images of that afternoon in the old crowded media centre where we shook with emotion, some wailed, several wept and cried aloud and most of us shuddered and found that the adrenalin that came from somewhere carried us through a workload that was never to be repeated again.

But this time, if it is to be the last, it will be a bitter-sweet experience; the memories will flood back, the wine will taste better as it rolls across the tongue, the images of that afternoon in the old crowded media centre where we shook with emotion, some wailed, several wept and cried aloud and most of us shuddered and found that the adrenalin that came from somewhere carried us through a workload that was never to be repeated again.

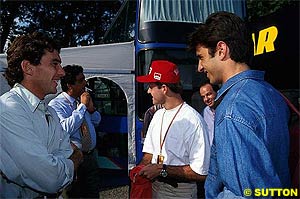

Barrichello was stunned, tearful, emotional and shaken. Senna was his mentor. Barrichello, a fellow-Paulista, was Senna's protege. They often traveled and spent leisure time together. The young Brazilian, to profound and universal amazement, not only survived, but returned to the paddock to tell his tale while his car was packaged into boxes and returned to England.

Barrichello was stunned, tearful, emotional and shaken. Senna was his mentor. Barrichello, a fellow-Paulista, was Senna's protege. They often traveled and spent leisure time together. The young Brazilian, to profound and universal amazement, not only survived, but returned to the paddock to tell his tale while his car was packaged into boxes and returned to England.

And that evening, long after the actions were over, as the shocks subsided into the sub-conscious systems, so the arguments and analysis began. Over crowded dinner tables in the villages and small towns, in dining rooms served by loyal and hard-working Italian families. The death, the tragedy that went with it and the shock affected everyone. It was a late night.

And that evening, long after the actions were over, as the shocks subsided into the sub-conscious systems, so the arguments and analysis began. Over crowded dinner tables in the villages and small towns, in dining rooms served by loyal and hard-working Italian families. The death, the tragedy that went with it and the shock affected everyone. It was a late night.

|

Contact the Author Contact the Editor |

Please Contact Us for permission to republish this or any other material from Atlas F1.

|

Volume 10, Issue 15

Special Issue

View from the Imola Paddock

The Feud with Prost

A Lesson in Safety

From Fangio to Schumacher

The Dark Side of the Man

Memories of May

Keith Sutton: The Senna Collection

Columns

Elsewhere in Racing

> Homepage |