Atlas F1 Special Columnist

As Voltaire wrote: to the living we owe respect, but to the dead we owe only the truth. Doug Nye tells the truth of Senna's place in motorsport history as he sees it

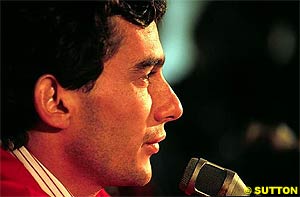

For many of his affirmed fans there wasn't then, and there will not be now, any acceptance that Ayrton Senna had anything less praiseworthy about his make-up as a man, and as a motorsporting hero. Given the nature of hero worship through the ages, that is to be expected and is both completely understandable, and acceptable. But where Senna the racing driver is concerned, the question needs to be asked: is the golden memory over-hyped?

I for one have always struggled to swallow the legend of The Great Ayrton Senna; though not in terms of his speed, his driving abilities, his exceptional sense of pace and of car control. For me he developed his undoubtedly supreme skills within a motor racing era in which driver invulnerability became a Formula One norm.

It was an era in which actions previously regarded as little short of murderous became not only commonplace but acceptable, and I have to say that with my background - entranced by racing undiminished from the mid-1950s forward, through the '60s, '70s. '80s and '90s - some of The Great Ayrton Senna's actions left me, and many of his peers, deeply unimpressed.

The logic of the argument withstands scrutiny. Ayrton Senna became renowned for ruthless intimidation of the men with whom he was forced to share track space. Sir Jack Brabham noted: "there's no doubt Senna was a great racer, the greatest of his era - but it was a safe era. He certainly pulled strokes others wouldn't attempt, and for years he got away with it. I honestly don't think we'd have let him get away with some of those moves in the '50s or '60s..." Australia's three-time World Champion was grinning his famously guileless grin, but his dark eyes glittered.

Sir Stirling Moss: "I get bored with being asked who was the greatest driver of all time. No way can different eras be compared. All you can do is recognise the candidates, so Senna is definitely and absolutely right up there. But in my period, for example, he wouldn't have survived for long driving the way he sometimes did."

Sir Jackie Stewart: "Senna was undoubtedly an all-time great. His death was a tremendous shock. But when Jimmy Clark or Bruce McLaren were killed the reaction was sheer disbelief that it could happen to them, with Ayrton Senna's accident the reaction was sheer disbelief that it could still happen to anybody. I think this is an important distinction; perhaps emphasising how, by the time of that Imola weekend, Formula One had become lulled into a sense of false security."

He had been kart racing in Brazil for eight formative years when he made his British Formula Ford debut in 1981. He won his third race, then two British FF Championship titles. But he also realised how within the modern 'sport', financial clout promoted mediocrity. To advance demanded not just talent, but big sponsorship too. Senna seemed repelled by this reality. He returned to Brazil rather disillusioned.

Typically he grappled with his doubts, resolved to persevere, and raised more finance for 1982. Unable to afford Formula Three he attacked Formula Ford 2000 instead. Twenty-one wins from 27 races later he started from pole in Thruxton F3 and won. Sheer class shone forth.

Through the following 1983 British F3 season he won another title and a Formula One test with Williams at Donington Park. Sir Frank Williams said: "He immediately impressed – despite his youth here, plainly, was a fellow racer."

His Formula One debut season followed, with Toleman, after his compatriot Nelson Piquet had probably vetoed his signing by Bernie Ecclestone for the Brabham team. Senna would recall: "I don't know whether Nelson said 'No' - but if he did I can't say I would have blamed him..."

He'd plainly adjusted quickly to modern racing reality. As journalist Alan Henry put it: "Over the next four seasons he was to develop into a man so totally absorbed by every detail of his work - his obsession - that only a few people, working alongside him, within his team, could make contact with him."

For 1985 he signed with Lotus-Renault and won his first Grand Prix. Team Lotus chief Peter Warr says: "Senna's class was so obvious that, when he joined us for '85, I offered him number one status, with Elio de Angelis to decide if he wanted to stay, but Ayrton turned it down, preferring to be joint number one... but he soon made it clear that he was number one on the track."

When he won at Estoril, in dangerously wet conditions, Alain Prost of McLaren had spun off on the straight. Prost had previously attacked Senna for blocking tactics during their leading dice at Imola. In 1986 Senna became unchallenged Lotus No 1, established his qualifying superstardom with nine pole positions, yet won only two more GPs. His Lotuses were Honda-powered in 1987 and he won twice more - again not often enough. By that time, utterly certain the world title should be his by right, his lack of regard for fellow drivers was over-evident.

The equally intense, driven and hyper-competitive Nigel Mansell had him by the throat, toes dangling, against the wall of the Lotus pit garage at Spa, seeking to jam the zip on Senna's overalls right up the Brazilian's nose. His disrespect had that effect on many, but it took an incandescent Mansell to react so publicly; he was what the oh so chummy Tony Blair might describe as "a hands-on kinda guy".

While Prost cloaked his committed professionalism beneath a friendly and relaxed surface, Senna's dour intensity and all-absorbing concentration upon achieving technocratic union with his car simply redefined such commitment. A personality clash seemed inevitable. And then Senna's self-belief seems to have bolted...

At Monaco 1988 he had the Grand Prix by the throat, but instead clattered the barrier at Le Portier. "I'd driven almost the perfect race," Senna would recall, "I had a moment at the Casino Square when the car jumped out of gear as I began to relax. I got back into a rhythm, but as I began to relax again I wasn't reacting ... and it caught me out."

He fled to his nearby apartment rather than report back to McLaren's management in the pits or paddock. As they wondered where the hell he'd got to, their egocentric prodigy agonised over his unacceptable error. "That woke me up ... it also brought me closer to God ... and has changed my life completely."

The driven man seemed suddenly - disturbingly - to be sharing the steering of his cars with God.

Back at Estoril for that year's Portuguese GP, Prost qualified on pole. Entering the long first turn perhaps he surprised his teammate by shouldering Senna wide. But the race was red-flagged. Cue a restart. This time Senna chopped Prost to take the lead, and as the Frenchman draughted up under the Brazilian's tail to repass ending that opening lap, Senna blatantly crowded him against the pit wall. Prost hung on to assert his now dramatically-threatened superiority, retaking the lead to win.

Later, he told Senna that if wanted to win the world title so badly that it meant driving like that, then the Brazilian could have it. He still made Senna work hard for it, but Japan 1988 saw the Brazilian finally achieve his life's ambition - for the first time.

He immediately set about ensuring it would be his alone in '89, and when that meant building political preference for himself with Honda, he set about achieving that too; devil take the hindmost, the defining selfishness of 'me first' being the committed professional racing driver's stock in trade.

Senna's apparent duplicity there really rattled Alain Prost.

It rotted the Frenchman's McLaren relationship from within. It was announced that Berger would take his place alongside Senna for 1990. Still, the world title again lay between Senna and Prost into the Japanese GP at Suzuka, where in effect Prost turned the tables on his teammate's intensity, and took him off in the last chicane.

Counter-accusation and recrimination filled the headlines and brought an impassioned Senna into conflict with the governing body, which authority he berated in impassioned press conferences, gulping back the impassioned tears of a small boy who had just been told 'No.'

At the end of 1990 the world title again lay between Senna and Prost - this time McLaren-Honda versus Ferrari. At Suzuka, Senna repaid his nemesis's chicane manoeuvre of the previous year by hustling the Frenchman straight off in the very first corner.

Both multiple-World Champions Jackie Stewart and Niki Lauda condemned Senna's action – but he professed total innocence – while Prost was literally speechless.

My personal respect for Senna the man died that day. I for one thought he should have been charged with bringing the sport into disrepute – and preferably banned.

By mid-summer 1991 it was Senna who was complaining of Nigel Mansell's "over-aggression." He said darkly: "perhaps I have let him have it a little too easy ... I should let the accident happen." Pot, kettle, and black spring to mind.

Grace followed, as with Mansell out of contention in the title-deciding Suzuka race Senna stepped aside in the final yards and presented his teammate Berger with the Japanese GP victory, while the Brazilian took his third world title. Post-race there his press conference then left the racing world agape. Of 1989 he spat: "I had won the race ... and was robbed badly by the system, and that I will never forget!" Further unburdening himself, he then not just admitted but proudly declared that he had intentionally pushed Prost off at the first corner in 1990.

Such blatant egocentricity - the unconcerned revelation of a truth previously so shamelessly denied and evaded - did more than diminish Ayrton Senna, and confirm my own opinion of what I had regarded as a repellent performance the previous year. As far as I was concerned – and, I know, many like me - his own words condemned him utterly.

When Michael Schumacher later demonstrated a Senna-like willingness deliberately to take out any threatening rival, past great Dan Gurney told me: "this generation do these things because they're confident they can do so without pay-back. In my day it would hurt, you might even kill somebody; you could kill yourself. But these days it's a victimless move. Senna proved you could do these things and get away with them. He sowed the seed. What burns me is that this doesn't just diminish the sport - it diminishes us all."

The manner of the Brazilian's subsequent death that tragic weekend at Imola was undoubtedly shocking - his unexceeded faith in his own invulnerability sadly misplaced.

But at the time I thought that nearly all of the media and much of the racing world had got it absolutely wrong.

Much of the public breast-beating and wrist-wringing after the deaths of Roland Ratzenberger and Ayrton Senna on successive days had not revealed the startling reality of how dangerous Formula One "had become".

Not at all. In fact, it had merely underlined how, for 12 long years, Formula One had fortunately "got away with it" - and rather than bewail what had just occurred, it would have been more realistic to celebrate that long fatality-free hiatus.

Ayrton Senna was a supremely gifted, capable and complex man in a complex sporting world. His legacy is self-evident - much of his private character was utterly admirable, but in reality much of his motor sporting legacy has been a demeaning liability.

All real history involves shades of grey, and this vivid man in many ways left a dark-grey shadow in his wake.

At the uttermost level of any major sport, tough characters abound. Some are simply tougher than others – both characters and sports that is. Some sports can exact the ultimate penalty. Self-evidently, motorsport is one such, and one of its toughest characters in recent memory was undoubtedly Ayrton Senna da Silva.

Right now, ten years after his death that traumatic weekend at Imola, the great Ayrton Senna is properly mourned. Undoubtedly the standard-setter of his era, Senna is rightly revered as a candidate for having been 'the greatest of all time'. Many who knew him best simply loved the man - although many of them also recognised he had a darker side; his remarkably chameleon character would make room without reservation for the young, the impoverished, the infirm and the very elderly.

Right now, ten years after his death that traumatic weekend at Imola, the great Ayrton Senna is properly mourned. Undoubtedly the standard-setter of his era, Senna is rightly revered as a candidate for having been 'the greatest of all time'. Many who knew him best simply loved the man - although many of them also recognised he had a darker side; his remarkably chameleon character would make room without reservation for the young, the impoverished, the infirm and the very elderly.

Ayrton Senna certainly developed his driven ambitions as a racing driver through a period in which it was relatively easy for such an intense competitor to become convinced of his own invulnerability. He was plainly comfortable that almost any manoeuvre could be justified - since experience showed there was hardly ever any physical price to pay, either by the driver who might commit the deed, or by his victim.

Ayrton Senna certainly developed his driven ambitions as a racing driver through a period in which it was relatively easy for such an intense competitor to become convinced of his own invulnerability. He was plainly comfortable that almost any manoeuvre could be justified - since experience showed there was hardly ever any physical price to pay, either by the driver who might commit the deed, or by his victim.

For 1988 Senna joined Alain Prost at McLaren-Honda; Senna's driven will plus Latin fire facing Tadpole's shrewd, cool, canny pace. Niki Lauda had once ruled McLaren's roost, stroking his superiority, until Prost joined the team and the Maus found "he suddenly had Concorde up his arse," as chief engineer John Barnard put it; now the same thing happened to the Frenchman.

For 1988 Senna joined Alain Prost at McLaren-Honda; Senna's driven will plus Latin fire facing Tadpole's shrewd, cool, canny pace. Niki Lauda had once ruled McLaren's roost, stroking his superiority, until Prost joined the team and the Maus found "he suddenly had Concorde up his arse," as chief engineer John Barnard put it; now the same thing happened to the Frenchman.

At Imola '89 Senna agreed with Prost they should not race each other on the opening lap, into the demanding Tosa corner - whichever McLaren led should command preference. Senna made the best start, no problem, but Berger's Ferrari crashed, red flag, restart again. Second time Prost led towards Tosa, confidently adopted the wide line, and found Senna shouldering through and away inside him.

At Imola '89 Senna agreed with Prost they should not race each other on the opening lap, into the demanding Tosa corner - whichever McLaren led should command preference. Senna made the best start, no problem, but Berger's Ferrari crashed, red flag, restart again. Second time Prost led towards Tosa, confidently adopted the wide line, and found Senna shouldering through and away inside him.

This time he blamed authority for preventing the organisers from swapping pole position to the left-side of the track to give the fastest qualifier benefit of the cleaner racing line. "I said if Prost gets ahead of me off the grid he'd better not turn in ahead of me, because he's not going to make it," Senna said. "You try to do your job properly and get fucked by stupid people ... it was a shit end to the Championship." And on, and on.

This time he blamed authority for preventing the organisers from swapping pole position to the left-side of the track to give the fastest qualifier benefit of the cleaner racing line. "I said if Prost gets ahead of me off the grid he'd better not turn in ahead of me, because he's not going to make it," Senna said. "You try to do your job properly and get fucked by stupid people ... it was a shit end to the Championship." And on, and on.

|

Contact the Author Contact the Editor |

Please Contact Us for permission to republish this or any other material from Atlas F1.

|

Volume 10, Issue 15

Special Issue

View from the Imola Paddock

The Feud with Prost

A Lesson in Safety

From Fangio to Schumacher

The Dark Side of the Man

Memories of May

Keith Sutton: The Senna Collection

Columns

Elsewhere in Racing

> Homepage |