Atlas F1 Technical Writer

Changes to the regulations mean that the teams will be penalised for using more than one engine per driver per weekend from the season opening Australian Grand Prix in ten days time, as well as a ban on most electronics. Atlas F1's technical writer Craig Scarborough reviews the changes, the 2004 field, and how the teams will cope with the new rules

Rule Changes

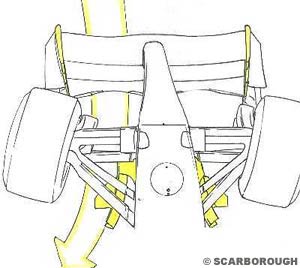

In order to reduce rear downforce the FIA regulated the rear wing down to only two upper elements. Initially this lost 5% rear downforce for the same drag; this downforce has been clawed back by detail design. Currently the extreme shape of the low drag rear wings seen in 2003 has been calmed, as the teams find the profiles and shapes to increase efficiency.

The latter rule change can actually increase the wing's efficiency, and the rule was introduced to increase space for sponsors. As the endplate is longer it protects against the wing tip vortex forming too early.

Last year the shrunken and drooped engine covers cost space for sponsors and the FIA responded with a non performance induced change. There is a little loss in flow to the rear wing and some negative effects when the car yaws (slides), but these are minimal.

No automated gearshifts and launch control

As part of a shake up in driver aids and to prove the effectiveness of the new FIA data-loggers, drivers will have to initiate gear changes from the steering wheel paddles, no longer having the electronics predict the best time for shifts. This increases the driver's dependency on shift lights and accurate timing, allowing possible errors in the races due to fatigue.

Launch control is now also banned; instead of releasing a steering wheel button to intimate a race start, the driver has to manage the clutch and shifts himself. In order to prevent reaction control being used to mimic launch control, limited engine management will be allowed up to a specified speed at the start; this will be monitored by the FIA data logger. This data logger will be subject to harsh penalties if the tamperproof seals are broken whatever the reason.

One engine per driver per weekend

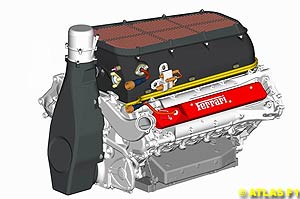

Reliability over the 800km will need to be matched to power output; after the first 100 or so kilometres the engine actually increases in power, then after a plateau power drops at the end of the engines 800km. Managing this power loss is a major issue for the manufacturers; dropping 1-2% of power by the races end or needing a few litres more oil over a race will cost in lap times and could see late race position changes. At least one major manufacturer is known to have a problem with power output towards the end of 800km.

Aerodynamics

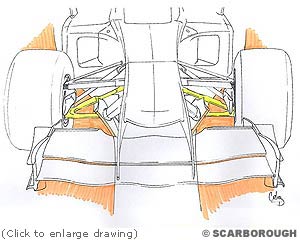

As teams are driven to find the 5% downforce lost at the rear from the new rules, front wing design is being compromised, both to balance the downforce produced at the rear and create as clean a flow to the rear wing as possible. So while in 2000 teams struggled to create downforce at the front from the rules raising the front wing, developments mean they are now able to make enough downforce just from the mid spans of the wing, leaving the centre section relatively flat to produce as clean a wake as possible to flow over and under the centre of the car.

This central flow passes under the nose and within the bargeboards, with some flowing under the splitter to feed the diffuser for rear downforce. The rest of the flow then parts over the splitter routing either into or around the sidepods. One aim in containing this flow is the tendency for the wake to rise upwards and go over the front suspension and sidepods, upsetting the flow to the rear wing.

Careful profiling of the wishbones and bargeboards conditions this flow to remain low and pass to the rear of the car under the flip ups. Meanwhile the dipped mid section of the front wing route the more turbulent wake outside the bargeboards to clear the rest of the bodywork. Front wing endplates and even the outer tips of the wing are now shaped to generate controlled vortices to shape the flow around the wheel without adding undue drag or affecting brake cooling.

Slimmer sidepods allow the flow to route around the rear wheels, keeping the right flow conditions over the floor and to the rear wing. In order to slim the sidepods the hot air generated inside by the engine needs to be expelled; this is done by many different solutions from louvered grills, small openings or chimneys. Each has its own merits when used in conjunction with the general flow over the car.

As the flow passes between the rear wheels, the rear brake ducts are used to curl the flow into the void created behind the wheel; as a result the ducts are oversize for their actual cooling needs and act more like turning vanes.

Team by Team

Ferrari

Having taken the titles in less than convincing fashion in 2003, the late roll out of the outwardly familiar F2004 was seen as a further disappointment. New year's testing has been with the car at tracks away from the mainstream teams, raising questions on the car's competitiveness. Many people also cite Bridgestone's tyres as a further indictment of the team's competitiveness.

The resulting cleaner flow in the middle of the wing is routed tight and low around the car, aided by the generous undercuts in the sidepods. The volume of flow that can be passed inside the bargeboard is greatly increased with these undercuts, creating a smoother path and less frontal area than squarer sidepods.

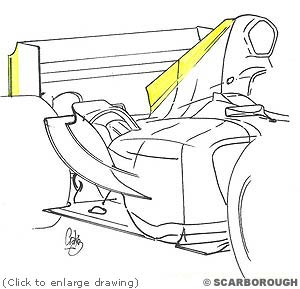

These split flows around the nose keep the rear wing in clean air. Also aiding the rear wing is the secretive flap attached to the engine cover and between the flip ups; this thin aerofoil shape has been seen in F1 before, acting not as a wing but a flow shaping device to reduce separation under the steeply angled rear wing.

Mechanically, an almost unseen change is a small shortening in wheelbase, pushing weight forward in combination with the lighter gearbox and more ballast in the splitter, helping the problems in getting the hot running Bridgestones well matched front to rear. The clever alloy gearbox is wrapped in carbon fibre for stiffness, mating with another recently unsung Ferrari component; the engine. With top reliability even in 400km form, the new 800km engine should see Ferrari on a par on performance with BMW, and perhaps ahead on reliability.

Overall the cars increment over its successful predecessors, and the teams usual strong pace of chassis and engine development, need only be matched by Bridgestone to see them challenge throughout the season.

Williams

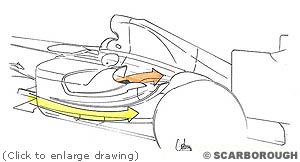

If all the talk about Williams tusk mounted front wing could power the car, the championship is already theirs! While visibly different, the 'walrus' nose acts just like Ferrari's; it's just that Williams have gone even further in the concept. While their nose surely provides aerodynamic benefits, it is countered by a lack of visible aero development around the rest of the car and impacts on the chassis stiffness and weight.

The resulting short nose is a smaller part in the set up, keeping obstruction to the clean inner flow to a minimum, as are the twin keels, spaced out to reach the bargeboards and providing a wide uninhibited path around the car. As you can see in the illustration the set up has created a wider path with less interruption within the tusks than on all the other nose shapes in use.

Williams have kept other innovations to a minimum; the engine and gearbox are both developed from the successful 2003 units, with the engine gaining a little weight for similar power and the gearbox gaining an extra gear (up to seven). Testing has seen Williams as the yardstick for others, their ultimate and repetitive lap-times proving the pace and reliability of the early released package. Michelin have been happy with their tyre development, improving their dry and crucially their wet weather tyres.

Overall Williams should be seen as the team to beat this year, as long as the new nose works and there are performance gains found around the rest of the car.

McLaren

McLaren's recent form has been puzzling; in 2002 they released the complex MP4-17, along with a switch to Michelin tyres and a 90-degree Mercedes engine. The season was a disappointment, with the new elements never gelling. 2003 saw the D-spec car racing until the hotly tipped MP4-18 was released; the car's debut was repeatedly delayed until it was eventually shelved.

Visually the MP4-19 takes its concepts from the 18, with a unique low nose tip, twin keels and Ferrariesque slim sidepods. Adrian Newey's take on the low downforce central front wing section, follows on from the 18, drooping the nose tip to right down to the front wing, even splitting the rear flap, and reducing the wing to two elements under the nose.

This low nose tip takes the flow under the middle of the wing, through the arch formed by the twin keels and around the car, aided by small keel-mounted turning vanes and supplemented by the larger mid placed bargeboards. It is no less effective than the other solutions described so far, but in developing the rear aerodynamics into a narrow shape the McLaren appears to have matched front to rear as well as the Ferrari.

In the illustration the dirty front wing flow is routed effectively by the bargeboards mounted to the end of the twin keels, creating a similar wide and clean route between the bargeboards to the Williams.

While McLaren's aerodynamics and use of Michelin tyres have brought the lap times, the mechanical parts of the package have been the weak point in testing. Following on from vibration of MP4-18's engine leading to failures, the new engine for 2004 appears to have similar issues. One of the first track tests to run on a new engine is temperature and vibration logging, not on the engine itself but on the chassis. McLaren have admitted that 'integration' problems between chassis and engine have been at the root of the car's lack of track time in tests.

Problems have also been attributed by the press to the gearbox, about which McLaren have been their usual secretive selves. It is widely known to use a primarily carbon fibre casing but this, and the rumoured twin clutch set up, have been suggested as areas of unreliability. Some of these are myths, as the carbon gearbox was running reliably in the MP4-17 test cars for the late part of 2002 and most of 2003; only when matched to the MP4-18's low routed exhausts did reliability issues hit home, and not in the gearbox but the suspension mounts.

Twin clutch rumours persist, and this sort of set up uses separate clutches for odd and even gears, allowing one gear to be driving the car and another already engaged for the next gear. The phasing of one clutch releasing as the other disengages creates an incredibly quick shift. This technology is only possible through the adoption of today's incredibly small clutches and clever gearbox control software.

However, the possibility of using the electronics to phase the clutches to keep drive to the road throughout the shift saw the FIA move to ban such systems, as they effectively form an infinitely variable transmission and hence provide more than the regulated seven rations. So it is doubtful McLaren or any other team (BAR were also so rumoured) have this sort of gearbox.

If McLaren are open about something as negative as reliability fears then one has to believe them. Yet fundamentally the car could be as competitive as either of their rivals; it just needs the team and Mercedes to work through the problems. If not a quick starter at Melbourne, McLaren should be seen as a threat by mid season.

Renault

If the years since Renault returned to F1 have been disappointing, then the resulting R24 looks set to turn around the team. But this is a short term view; the team have lost their two top technical staff from the chassis and engine departments. Mike Gascoyne and Jean Jacques His left the team, the latter too early to add to the new engine programme. The effects of these departures will not be seen in the initial pace of the 2004 package.

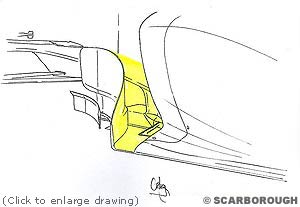

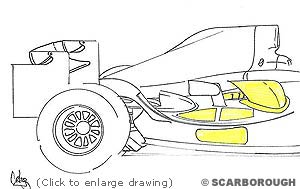

The cost of this solution is cooling. Renault pioneered the chimney winglet combinations, and this year's car featured the largest, most sculpted chimney yet seen. But even this is not sufficient to clear the hot air expelled from exhausts and radiators; a myriad of openings are available to supplement the cooling, from a low opening to aid the downward facing radiator to three over the exhausts.

Suspension follows conventional wishbone angles, Renault preferring not to droop the upper wishbone to get the camber changes recommended by Michelin, with the layout of the front dampers also following established practice. Gearbox cases are now solely made in cast titanium, and not the split carbon/Ti version of 2003.

Recent testing has proven the car and engine combination to be on a par with the top three, raising the question of whether we will see a true top four this year.

BAR

After a low key 2003 season the new BAR technical team, lead by Geoff Willis, were able to pen their second clean sheet design for 2004. Initially similar looking to the 2003 car, the new BAR 006 slowly reveals its details and developments from the 005. Aerodynamically the car lacks really clever progressive solutions, but does adopt BAR first fully raised nose, high enough to mount both the front and rear of the lower wishbone on a single keel.

On the chassis side the carbon gearbox, lighter engine and adoption of MMC has seen an increase in the amount of ballast they can run. Now placed in the removable splitter section and under the driver's thighs, the removal of some of this ballast has been highlighted as a reason for the team pace. It is more likely that, albeit with low fuel, the migration to Michelin tyres and improved output from Honda has lifted BAR clear of the midfield.

Honda's development has been much underplayed; only two years ago the unit was cited as heavy, unreliable and lacking power. The final Suzuka spec engine in 2003 was very light and powerful, if not 100% reliable. Work to progress this to an 800km unit was met with total success according to Honda. Recent testing failures have been attributed to components already up to 800km and being yet further lightened to release more power.

BAR's pace in testing may not be proof they are the quickest car overall but their pace has eclipsed the other midfield teams, who have failed to bring the fight nearer to the top four.

Sauber

Yet it has to be said that familiar Sauber trademark designs are amiss on the new car, instead replaced with solutions all too familiar on a Ferrari, such as the diffuser and splitter plate, soon revised from the Sauber-esque versions on the launch car. Even the radiator layout has been transferred. Seeing as Sauber have struggled with crash tests, it could be proved not all data was exchanged between the teams.

Sauber can be expected to be reliable in a season where engine reliability counts, but as yet no signs of real pace have emerged from the Swiss outfit.

Jaguar

As the star of short runs in 2003 Michelin shod Jaguar could have looked forward to 2004, with a car developed from their understanding of the R4 and cured of its rear tyre eating set up and engine reliability problems. But the overly conservative R5 has not been a star in testing.

Playing their trump cards, which are their conservative approach and Michelin tyre supply, worked in 2003. But Cosworth's supply of all-new V10s to both Jordan and Jaguar will be a strain on their resources, especially with the new long engine life rules adding pressure to their previously unreliable engines. It is only with lots of track time through engine reliability that Jaguar will be able to progress from their promise in 2003.

Toyota

Always a dark horse before the season starts, Toyota's huge resources openly on show at their launch are proof of their commitment to winning. But last year proved that resources and money do not automatically bring success. Starting from a clean sheet with no F1 experience was part of Toyotas ideology, but this has also been their weakness, being unable to have the archive of knowledge and data to draw upon when unusual problems crop such as with their kerb sensitive aerodynamics in 2003.

Engines have been a success for the team, the RXV03 being rated amongst the top few in 2003, yet this was with the developments for the 800km engine being directly applied to the 2003 race unit. This impressive fact suggests the RXV04 should remain at the top of the engine ladder. Toyotas huge resources extend to the in house manufacture of gears and electronics, an unusual step in a world of dedicated specialists providing these parts.

Disappointing form in early testing suggests more time is needed to develop the Toyota ideology into true pace; Gascoyne's influence will not be felt until at least mid season, so a slow start to the year for this automotive giant can be expected.

Jordan

Adopting a single keel goes against the arm-chair spectator's view on car design, but should be considered prudent for a team unable to design enough weight out of the car as they'd like with the single keel being lighter for the same stiffness and for a small aero penalty.

This is no doubt aided by a lower 90-degree engine and improved diffuser shape due to the new gearbox. Neat treatment, albeit of limited performance gain, which sees the exhausts routed wide and low exiting through in the sidepods.

Minardi

Still using 72-degree Cosworth CR3 engines, re-tuned for longer life at the cost of power, pace will not be improved over the PS03 by its power output. One unique detail on the PS04B is the rear wing endplate, which forms the regulated 10cm rearward extension with a vertical flap acting to create lower pressure under the rear wing.

This season sees several technical rules changes to the chassis, from the details of the rear wing and engine cover to the removal of certain driver aids. However these had little effect on the march of development over the closed season.

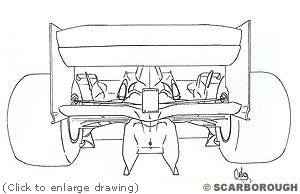

The rear wing itself can only use two upper elements and endplates are now 10cm longer

The rear wing itself can only use two upper elements and endplates are now 10cm longer

Engine covers are now mandated to extend to a specific height and width ahead of the rear axle

Engine covers are now mandated to extend to a specific height and width ahead of the rear axle

This is much further reaching rule than the previous ones. Should a driver need to change an engine for whatever reason, he will be docked ten grid places. This effectively doubles the life of the engine to 800km. Teams will have to have to juggle track time against engine wear, probably running lower revs on Friday and Saturday mornings to preserve engine life. Equally should a driver damage his race car for whatever reason the engine must go with him into the spare. Teams will have to decide whether repairs should be made to the race car or put the race engine in the spare car.

This is much further reaching rule than the previous ones. Should a driver need to change an engine for whatever reason, he will be docked ten grid places. This effectively doubles the life of the engine to 800km. Teams will have to have to juggle track time against engine wear, probably running lower revs on Friday and Saturday mornings to preserve engine life. Equally should a driver damage his race car for whatever reason the engine must go with him into the spare. Teams will have to decide whether repairs should be made to the race car or put the race engine in the spare car.

Looking at the car itself, while it is evolutionary it is in fact quite a step on from the F2003GA, making the aerodynamic shape of the sidepods even more extreme and matching them to the new front wing profile, taking another step on from the cars established and efficient aero philosophy. The new front wing works as with most other teams, only working the shape hard where the trailing flow can be routed away efficiently, the defined kink in the profile aiding to turn the turbulent flow around the car.

Looking at the car itself, while it is evolutionary it is in fact quite a step on from the F2003GA, making the aerodynamic shape of the sidepods even more extreme and matching them to the new front wing profile, taking another step on from the cars established and efficient aero philosophy. The new front wing works as with most other teams, only working the shape hard where the trailing flow can be routed away efficiently, the defined kink in the profile aiding to turn the turbulent flow around the car.

The primary element in the Antonia Terzi designed Williams nose is the wide spaced tusks mounting the front wing. These are now placed along a longitudinal line that also places the bargeboards and sees the downforce producing dips in the front wing start; they act as part of the turning vane package, keeping the clean air inside the bargeboards and the dirty air outside.

The primary element in the Antonia Terzi designed Williams nose is the wide spaced tusks mounting the front wing. These are now placed along a longitudinal line that also places the bargeboards and sees the downforce producing dips in the front wing start; they act as part of the turning vane package, keeping the clean air inside the bargeboards and the dirty air outside.

Disappointment with the even more complex 18 vibrating and melting itself to pieces around test tracks was tempered with the surprise pace of the 17D, keeping it in title contention until the last race. So when McLaren released the MP4-19 quietly in December last year, the question was whether it would inherit 17D or 18's genes.

Disappointment with the even more complex 18 vibrating and melting itself to pieces around test tracks was tempered with the surprise pace of the 17D, keeping it in title contention until the last race. So when McLaren released the MP4-19 quietly in December last year, the question was whether it would inherit 17D or 18's genes.

The R24 is as radical a departure from Renault's recent conservative aero philosophy as Williams walrus nose. In 2003 the pace of Renault's aerodynamic development was a signal that the team were more than capable of delivering more on the concept side. The new approach was to take the conventional nose and match it to sidepods, sculpted and tightened even more exaggerated than Ferraris. Aided by the narrower engine configuration and clever radiator layout, Renault has achieved efficiency by providing a clearer route further downstream than that of their competitors.

The R24 is as radical a departure from Renault's recent conservative aero philosophy as Williams walrus nose. In 2003 the pace of Renault's aerodynamic development was a signal that the team were more than capable of delivering more on the concept side. The new approach was to take the conventional nose and match it to sidepods, sculpted and tightened even more exaggerated than Ferraris. Aided by the narrower engine configuration and clever radiator layout, Renault has achieved efficiency by providing a clearer route further downstream than that of their competitors.

Renault's engine facility in Viry Chatillon needed a quick development path away from the vibrating wide angle engine when the 800km rules were defined. As Renault had no data on 90-degree formats the narrower 72-degree design was chosen, but this is no warmed over unit from the successes of the nineties; this is a totally new engine taking data from the two previous programmes.

Renault's engine facility in Viry Chatillon needed a quick development path away from the vibrating wide angle engine when the 800km rules were defined. As Renault had no data on 90-degree formats the narrower 72-degree design was chosen, but this is no warmed over unit from the successes of the nineties; this is a totally new engine taking data from the two previous programmes.

Bargeboards are reduced to a single vane within the front suspension; neat touches like a drooped wishbone fairing route the flow around curved shouldered sidepods to pass under a complex hot air outlet ahead of the rear tyres. The flow from under the nose is routed low and under the flip up, while the hot air flow from the duct is routed well clear of the bodywork.

Bargeboards are reduced to a single vane within the front suspension; neat touches like a drooped wishbone fairing route the flow around curved shouldered sidepods to pass under a complex hot air outlet ahead of the rear tyres. The flow from under the nose is routed low and under the flip up, while the hot air flow from the duct is routed well clear of the bodywork.

If Sauber have actually copied the 2003 Ferrari from original drawings, as widely believed, then they have lost something in translation as the Sauber is not yet the same car on pace as the F2003GA's being tyre tested by Ferrari. Jean Todt of Ferrari admitted that data is shared between the two teams technical staff, but he stopped short of saying the exterior shape of the F2003 was part of the exchange; in fact he seemed surprised the suggestion was raised as other teams had copied elements of the car in some form or another.

If Sauber have actually copied the 2003 Ferrari from original drawings, as widely believed, then they have lost something in translation as the Sauber is not yet the same car on pace as the F2003GA's being tyre tested by Ferrari. Jean Todt of Ferrari admitted that data is shared between the two teams technical staff, but he stopped short of saying the exterior shape of the F2003 was part of the exchange; in fact he seemed surprised the suggestion was raised as other teams had copied elements of the car in some form or another.

Wary of recent failures in pushing design boundaries, and still consolidating their technical and management teams, Jaguar has been unwilling to divert from their established design. Detail changes exist of course, for example the almost longitudinal radiators and kinked front wing, but these are tempered with bulky cooling outlets and broad sidepods blocking the coke bottle shape.

Wary of recent failures in pushing design boundaries, and still consolidating their technical and management teams, Jaguar has been unwilling to divert from their established design. Detail changes exist of course, for example the almost longitudinal radiators and kinked front wing, but these are tempered with bulky cooling outlets and broad sidepods blocking the coke bottle shape.

Buying in Mike Gascoyne to lead development from 2004 was another expensive step in the right direction. The TF104 is the most conventional development of Toyota's four single seaters. Eschewing bulky sidepods and hot air outlets for more Ferrari inspired versions, but preceded by the smallest of turning vanes, Toyota have taken inspiration from across the grid.

Buying in Mike Gascoyne to lead development from 2004 was another expensive step in the right direction. The TF104 is the most conventional development of Toyota's four single seaters. Eschewing bulky sidepods and hot air outlets for more Ferrari inspired versions, but preceded by the smallest of turning vanes, Toyota have taken inspiration from across the grid.

With the tightest of budgets the Jordan team wheeled out a surprisingly different car to that expected. Major alterations to the chassis, with a single keel and a new shorter gearbox, were matched with similar aerodynamics that were as big a step as other changes according to the team.

With the tightest of budgets the Jordan team wheeled out a surprisingly different car to that expected. Major alterations to the chassis, with a single keel and a new shorter gearbox, were matched with similar aerodynamics that were as big a step as other changes according to the team.

As is traditional for the small team, Minardi rolled their car out late and last. On first sight the car is a replica of the 2003 PS03 and not the re-liveried Arrows PS04. Detail alterations to the roll structure are all that's apparently different, despite Minardi's statement that the cars adopts practices form both cars. Some Arrows influence could be seen on the front wing shape, but as the Arrows used fundamentally different nose and keel arrangement the similarity might not so beneficial.

As is traditional for the small team, Minardi rolled their car out late and last. On first sight the car is a replica of the 2003 PS03 and not the re-liveried Arrows PS04. Detail alterations to the roll structure are all that's apparently different, despite Minardi's statement that the cars adopts practices form both cars. Some Arrows influence could be seen on the front wing shape, but as the Arrows used fundamentally different nose and keel arrangement the similarity might not so beneficial.

|

Contact the Author Contact the Editor |

Please Contact Us for permission to republish this or any other material from Atlas F1.

|

Volume 10, Issue 8

2004 Season Preview

The Atlas F1 2004 Gamble

The 2004 Drivers Preview

The 2004 Teams Preview

The 2004 Technical Preview

The Formula One Insider

The Time to Self Level

The New Deal

2004 Countdown Facts & Stats

Columns

On the Road

Elsewhere in Racing

The Weekly Grapevine

> Homepage |