Atlas F1 Senior Writer

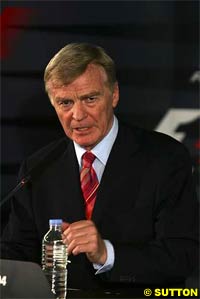

There are men of action and men of words. Although FIA President Max Mosley is known for being both, it is his gift for the English language that distinguishes him from everyone else. Atlas F1's Thomas O'Keefe has been following Mosley for several years now and - a week after the controversial Briton announced his resignation - he brings the story of Mosley's tenure, in his own words

Now Max Mosley says he is packing it in from the somewhat political post to which he was elected, the Presidency of the FIA. All in all we were lucky to have had Max Mosley grace Formula One for so long with his vivid language and forceful tongue, by turns acerbic, witty and serious but always precise and thoughtful. Of the 500 plus members of the regular Formula One press corps who have among them an astonishing number of highly intelligent Wordsmiths, not one of them was his equal and they all knew it.

Born into controversy when, as an 11-week old infant Max, his father, Sir Oswald, and his mother, Lady Diana Mosley, were both arrested and imprisoned without benefit of due process under the infamous wartime Rule 18B of the Emergency Powers Act (1939), Max seemed to gravitate throughout his career to verbal fisticuffs and controversies. In the early days, it was Max in his role as legal advisor to Bernie Ecclestone's Formula One Constructor's Association, challenging Jean-Marie Balestre and the FIA Establishment, before Max and Bernie swallowed them all up and became the Establishment.

In later days, he sparred with rebel driver Jacques Villeneuve, who was critical of the grooved tyres and other changes introduced by the FIA in 1998 to slow the cars down for safety reasons, a process being repeated again in the current era.

Max Mosley also crossed swords with the team owners on many occasions over regulatory issues, singling out for particular ridicule the verbally outgunned Ron Dennis of McLaren, who seemed always to be in disagreement with whatever Max Mosley was proposing, but was hard pressed to keep up with the barbs hurled back at him by the Oxford-trained barrister. On occasion, Max even challenged the redoubtable Bernie Ecclestone, his friend of 30 years, dunning him for $60 million at one point as the down payment for a commercial broadcasting rights deal Bernie had made with the FIA.

Along the way, Max Mosley even took on the entire Government of Europe – the European Commission – and won a stunning antitrust case brought against Formula One, drawing on the litigation skills he learned as a top barrister before he entered the world of motorsport. He also tangled with no less a pillar of journalism than The Economist, when an unflattering portrait was published of Bernie Ecclestone and the finances of Formula One without so much as a request for an interview from the FIA. With his words as weapons, he has been at the forefront of the pinnacle of motorsports since the very outset of modern Formula One, having assisted in the drafting of the Concorde Agreement, the Constitution of Formula One, in 1981, which expires not too long after Max Mosley departs. In effect, he wrote the rules of the game and then operated within them for 23 years.

In his Magny-Cours press conference on July 2, 2004, amplifying upon his reasons for stepping down in October 2004 from the FIA Presidency, he said in response to a question that he has no plans to write his Memoirs, which would be a great shame given the wealth of his experiences and his peculiarly incisive and pungent way of putting things.

So for now we are left with what he has said so far, as reflected in this thumbnail sketch of the wit and wisdom of Max Mosley, on subjects great and small.

Tallish Max on Bernie's jockey-like size:

"When I talk to Bernie, I always imagine that I'm talking to him eye-to-eye!"

(Daily Telegraph interview, July 1997)

Max on his remarkable father, Sir Oswald Mosley, founder of the British Union of Fascists in the pre-war years before Max was born in 1940:

"When you are a child everything is natural – normal you think. It [the family's controversial nature] was always there. But you have got to remember that my father started life in politics at the age of 21, just 22, as a conservative MP, then he was a labor MP, then he was in the labor government: so he had a whole conventional political career [and] behind the scenes he was still friendly with a great many of the conventional politicians in England and so it wasn't quite like being sort of right out [of it]. The general public probably saw him as a strange person but it was a very curious thing, a strange sort of family."

"Winston Churchill was more or less like an uncle to my mother. She was very, very close to Churchill. And she was friendly with Hitler as well; she was probably about the only person who was!"

Max's memory of Jim Clark's accident during a Formula Two race at Hockenheim on April 7, 1968, which was 28-year-old Max Mosley's first F2 race:

"I just remember seeing the ambulance parked off to one side of the track [and thinking that] someone had obviously gone into the trees. I also remember catching Graham Hill and overtaking him, which was of the high points of my career. It was wet, the tyres on the two Team Lotus cars [Firestone] were inferior to the ones [Dunlops] I had, so it had nothing to do with skill: I was never any good. But I finished 10th and Hill finished 11th."

Max on his accident in 1969 at the 14.1 mile Nurburgring in his F2 Lotus that ended Max's days as a race car driver:

"As Lotuses were apt to do in those days, the front wishbone dropped off the suspension upright and caught in the wheel on the flat out fifth gear right-hander just coming out of the trees after Schwalbenschwantz (Swallowtail).

"The left front wheel stopped turning and I thought, 'This is trouble', and I ended up in the caravan park. Then I took [my customer F2 Lotus] back to Lotus and they fixed it. And I took it out to Snetterton to test it and the brake disc sheared off while I was braking; as you might imagine, it's very difficult to control the front of the car when the front brakes fail. I had had about enough then and I took the car back to the Lotus racing division and turned it back to Colin Chapman, who promptly sold it to some Germans. It was evident that I wasn't going to be World Champion.

"When I raced in Formula Two in the Sixties, I used to ring up organizers to ask for start money. Usually they would say, "Sorry, we have given it all to Rindt and Stewart, but you are very welcome to come along and join." (FIA Press Conference, September 7, 1996)

On the anonymity of British Club racing:

"There was always a certain amount of trouble [being the son of Sir Oswald] until I came into motor racing. And in one of the first races I ever took part in there was a list of people when they put the practice times up as they do. Everyone stood around looking at the times. All the competitors in that class of racing looking at the list and they came to my name and I heard somebody say, 'Mosley, Max Mosley, he must be some relation of Alf Mosley, the coachbuilder.' And I thought to myself, I've found a world where they don't know about Oswald Mosley." And it has been a bit like that in motor racing: nobody gives a darn."

Max on the basics of motorsport:

"Should motor racing be a technological contest between the teams, with the driver present merely as a passenger; or should it continue to be a fundamentally human sport which opposes two or more drivers using very high technology machines? We took the decision six years ago to make sure that it was a human contest. We were prepared to accept the high technology, but only as long as the driver had to control the car himself.

"The FIA believes that a driver has three fundamental skills. These are: steering the car, using the brakes and – in a high-powered machine like a Formula One – controlling acceleration." (FIA Press Conference, April 7, 2000).

Max on grooved tyres and slowing Formula One cars down in the interest of safety:

"We have got to make sure that the cars don't keep getting faster and faster with some very competent people trying to make sure they do go faster and faster. We are always told reduce the aerodynamics. Trouble is we've learned from experience that it never succeeds. For thirty years we've been constantly trying to reduce the aerodynamic potential of the cars to keep the speeds in check and this has failed.

"If we release the tyres then the speeds will go up and we know that the energy of the impact is directly proportional to the grip of the car and the tyres are a very big part of the grip of the car. So [the tyres] are something we can get hold of and it does not matter what the engineers do. If we reduce the amount of rubber on the road the car will slow down. The principle is elementary. In the end, if they are on bicycle tyres – and obviously you don't want to go to that extreme – they have 10,000 horsepower and all the downforce they want and they will not go quick enough in the corners to hurt themselves. So it is finding a balance that is our objective.

"But the grooved tyres were probably the most import contribution to keeping speed and therefore safety under control."

Max on Bernie being in favor of slicks:

"Yes, Mr. Ecclestone did suggest a return to slick tyres. Bernie gets most things right, but not even he is right all the time about everything." (FIA Press Conference July 12, 1999)

Max on Overtaking:

"If anybody ever bothered to do an analysis, rather than jumping to conclusions, he would find that there is a significant amount of overtaking in F1 races. The fact of the matter is that when these drivers need to overtake, they can do so if they wish. But such is the attention on modern Formula One racing that if they're running in the first six places, modern drivers are very reluctant to risk losing points at that stage. But just put a top driver at the back of the field, and you'll see some overtaking." (FIA Press Conference, December 7, 1999)

Max on the incident at Dry Sack Corner between Jacques Villeneuve and Michael Schumacher at Jerez in 1997:

"It was an instinctive reaction. If we thought it was premeditated then we would have had to take a very serious view. It is still a very serious matter and it is a major penalty we have imposed. In this particular instance, both Villeneuve and Schumacher were under enormous pressure. They had one point between them, they had people shouting in their ear 'he is just one second behind you' and the pressure, in those circumstances, is enormous.

"Schumacher did the wrong thing, obviously, but all the evidence points to him reacting instinctively. Had he thought about it, for one second, he would have allowed Villeneuve through. Schumacher is a human being and every now and then he will make a mistake. He admitted he did it deliberately, but instinctively, and it was the wrong thing to do," (November 11, 1997)

Max upon reading Atlas F1's Bulletin Board comments on Face-to-Face with Max, July 4, 2000:

"I really enjoyed reading the internet notes, but it is quite alarming how little most of the correspondents know about the technology of Formula One. As a general rule, the stronger the opinion, the less the holder seems to be able to justify it."

Max on the state of Formula One when Bernie Ecclestone took over commercial F1's interests:

"Mr. Ecclestone runs one of many possible businesses in motor sport. The FIA would be very happy if someone where to do the same in rallies or in sports car racing, where the potential is every bit as big as Formula One. Don't forget when Mr. Ecclestone started in 1970, sports car races like Le Mans, Daytona, Kyalami and the Nurburgring were bigger and more popular than Formula One events. Some Formula One races in 1969 had only 13 cars on the grid, of which perhaps 8 were serious racers." (FIA Publication, April 2000)

Max on the particular genius of Bernie Ecclestone in wrapping up worldwide TV rights:

"Bernie has a sound method of dealing with [the multi-jurisdiction] difficulties. He draws up a list for himself of anyone who, under any interpretation of the legal system, could possibly own rights. It could be us, the FIA, or it could be a local promoter, the local organizer, in certain countries the local federation, the local government, the teams anyone he can think of. What he then does is to acquire, for consideration, the rights to each Grand Prix from every single person or body that could possibly be involved. As a result, his situation is invariably secure, because he can point out that it doesn't matter who is the true original owner of the rights under the local jurisdiction whoever it is, Bernie has bought them from him. That strengthens his position in the event that anyone's entitlement to sell him the broadcasting rights should be subsequently challenged. If the [European] Commission, for example, decides to inform him the FIA never had the right to sell him anything.

Max's comment on the story in "Eurobusiness" on the European Commission's Karel van Miert, the chief prosecutor of the EC's antitrust case against Formula One, as the most powerful man in Europe:

"The magazine in question is, I think, in some way, connected to Bernie Ecclestone. And knowing Bernie, who must never be underestimated, it may all be a very elaborate joke . . . As far as we are concerned, van Miert is a spent force." (FIA Press Conference, July 10, 1999)

Max's letter dated August 21, 2000 to the Mr. Bill Emmott, Editor of "The Economist", commenting on a July 15, 2000 article called "Grand Prix, Grand Prizes" and an accompanying editorial called "The Secret Finances of Formula One":

"Perhaps wisely, neither you nor the journalist concerned have made any attempt to answer the points raised in my letter. . . Your reporter should have sought an interview with me and used it to go through the whole story. All serious writers do this . . . It is widely known in the City what nonsense most of the story was and how misconceived your editorial. Even in Brussels it caused no more than mild amusement because it was so obviously flawed.

"None of this can be good for "The Economist", so perhaps you will allow me another little homily. It is much easier to destroy the reputation of a great journal than to build it. All it takes is poor journalism and lax editorial control. Not seeking an interview with me was undoubtedly poor journalism; not insisting that this be done was, at the very least, lax."

Max on the possibility of an amended Concorde Agreement (February 2004):

"The Concorde Agreement [negotiation] has barely started. For a number of reasons I don't think we will have agreement in the foreseeable future."

Max on the unlikelihood of the GPWC mounting a rival series to Formula One:

"I don't believe in such a hypothesis . . . .But if [a rival series] were to happen it would be under the FIA. The carmakers, however are interested in competing in the same championship won by Fangio and Clark, not in creating a new one." (Gazzetta dello Sport, February 23, 2001)

Max Mosley's remarks at 10 Downing Street with Prime Minister Tony Blair on October 16, 1997 as to the effects on the UK motorsports industry of banning tobacco advertising (as summarized by the Blair's Private Secretary):

"Proposals for EC Directive put forward by Luxembourg Presidency make no sense. If F1 leaves Europe, you will get more, not less sponsorship on TV. A perverse consequence. Subsidiarity suggested national legislation better anyway. Great pressure for F1 to (move) to Far East. Ran through list of countries wanting a Grand Prix. Tobacco companies build circuits. Had been to see Tessa Jowell and Tony Banks. Not sure if we understood."

Max Mosley letter dated January 22, 2004 to Mr. Antonio Vitorino, Member of the European Commission, calling for disciplining the EC's spokesman:

"Your spokesman, a Mr. Petrucci, has been widely quoted in the press as saying 'Mr. Mosley is not above the law' and that the Formula One teams have woken up to the European Arrest Warrant too late.

"Both allegations are unacceptable. The one implies that I wish to be above the law, which is untrue and libelous. The other is also false, in that the teams and their representatives have had innumerable meetings with Commission officials on the European Arrest Warrant, culminating in a meeting on 7 July 2003 with the Director-General of your directorate, Mr. Jonathan Faull, together with a member of your cabinet.

"Your spokesman has clearly not made the slightest effort to ascertain the truth before speaking to the press. I leave it to you to take appropriate disciplinary action. However, this is not the first time that a Commission spokesperson has sought to damage the FIA. On the last occasion, action in the European Court of Justice resulted in a formal apology from the Commission."

"According to the team principals, in the event of a serious accident such as the one involving Ayrton Senna in 1994, a local magistrate could use the EAW procedure to order the immediate arrest of team personnel in their home country and have them taken in custody to the country where the accident occurred, where they could be locked up until trial."

Max commenting on the European Commission's statement supporting EAW:

"Mr. Vitorino [Member of the EC] is clearly unaware that one EU government has already confirmed that the relevant provisions of the European Arrest Warrant do not apply to sport. We anticipate that other EU governments will agree. No F1 team considers itself above the law but they will not race where they do not feel safe. Mr. Vitorino may not understand this but those who apply EU laws do." (FIA Press Release, January 21, 2004)

Max Mosley letter dated January 30, 2004, to Mr. Jonathon Faull, Director General, Justice and Home Affairs, European Commission:

"No one in Formula One or, I think, in the wider sports community questions the right of a country to enforce its laws and to prosecute any individual it thinks guilty of a crime. A person or team which does not like the law in a foreign country has the right not to compete there, but no right to criticize the law. Our problem with the EAW is procedural, namely the risk that its provisions might be used in an unfortunate manner by an ambitious magistrate or in the immediate emotional aftermath of a sporting tragedy. After arrest and imprisonment, however brief, a subsequent acquittal or release on bail is of little comfort.

"It would be very helpful if the Commission were able to express the view that the EAW is aimed at genuine and intentional criminal activity and is not intended to cover an involuntary act or omission occurring in the ordinary course of a sporting activity. We truly appreciate that such an expression of opinion by the Commission would not bind a member state. Nevertheless it would have considerable persuasive value."

Max on his job and the compensations of being President of the FIA:

"You get great privileges and a very interesting life as President of the FIA, but the object is not to make money. It's not a paid job, it's a job that is done out of interest...

"One of the things that people probably don't appreciate. . .it looks as though one goes around in the jets and the limos but the real job is you get into office about 9 o'clock in the morning and you work solidly until about 7 o'clock in the evening. And that is somebody who works quickly, in fact too quickly because I don't read things properly sometimes. It is massively hard work because it is all of the road side, all of the racing side and endless difficulties. quarrels in countries about who has the sporting power, it is absolutely never ending, and there is a certain point you start thinking there is probably more to life than this and also you feel that if you are losing interest a bit you don't perform well if you are not 100 percent engaged. But it is very hard work.

"I haven't got some amazing new job lined up and happily, as far as I know, I'm perfectly healthy."

Max on his memoirs:

Max on his retirement:

"Sometimes one says to oneself, isn't it actually probably more fun to sit on the beach with an interesting book than to sit here having these [interminable team owner] discussions?" (Magny-Cours FIA Press Conference, July 1, 2004)

Max briefing Michael Schumacher prior to FIA Presentation on Road Safety in Dublin in April 2004, (quoted in F1 Racing):

Max: ". . . 1.2 million people killed on the roads world wide every year . . ."

Schumacher: "Er, 1.2 million people killed every year," [Schumacher] repeats, visibly shocked.

Max: " ...Do the sum. That's 3,200 people every day. A 9/11 every day."

The product of the best schools in England and Europe, FIA president Max Mosley is smart, clever, politically skilled and wise enough to have become Prime Minister of Great Britain, had his father, Sir Oswald Mosley, not burned that particular bridge for him by becoming the embodiment of the British Fascist movement in the 1930's.

But his legacy will not be limited to presiding over the explosive and worldwide growth of Formula One during his tenure. Probably his keenest personal satisfaction comes from putting the full weight of the FIA squarely behind road safety initiatives Max hoped would help in reducing the slaughter on the world's highways, including badgering the automobile manufacturers into building safer cars that were evaluated annually under the New Car Assessment Programme (NCAP) which the FIA shone the spotlight on, to expose participating carmakers to praise or shame depending on the results of the annual safety/crash testing program sponsored by NCAP.

But his legacy will not be limited to presiding over the explosive and worldwide growth of Formula One during his tenure. Probably his keenest personal satisfaction comes from putting the full weight of the FIA squarely behind road safety initiatives Max hoped would help in reducing the slaughter on the world's highways, including badgering the automobile manufacturers into building safer cars that were evaluated annually under the New Car Assessment Programme (NCAP) which the FIA shone the spotlight on, to expose participating carmakers to praise or shame depending on the results of the annual safety/crash testing program sponsored by NCAP.

Max on his remarkable mother, the late Lady Diana Mosley, who was imprisoned and held without trial at Holloway Prison when Max was 11 weeks old:

Max on his remarkable mother, the late Lady Diana Mosley, who was imprisoned and held without trial at Holloway Prison when Max was 11 weeks old:

"So if you have a responsible governing body you must have a final point of defense and that for us is the grooved tyres. Now if we had some magic way of reducing the downforce or, even better, reducing the downforce and increasing the ability of the cars to run close to each other in the corners we would take it but we know there isn't.

"So if you have a responsible governing body you must have a final point of defense and that for us is the grooved tyres. Now if we had some magic way of reducing the downforce or, even better, reducing the downforce and increasing the ability of the cars to run close to each other in the corners we would take it but we know there isn't.

"Bernie's approach then was make an offer to race organizer: FOCA would offer to race for a stated fee, while also taking over the TV rights to the race, at least outside the country. Gradually, through the Seventies, he acquired the TV rights to all the races. This enabled him to reach an agreement with broadcasters for them to show the entire championship. This allowed him to build up the largest possible audience and obtain the widest possible TV coverage. As a result, the TV rights gradually became valuable. By the time the first Concorde Agreement was signed in 1981, Bernie had acquired the TV rights to virtually every Grand Prix."

"Bernie's approach then was make an offer to race organizer: FOCA would offer to race for a stated fee, while also taking over the TV rights to the race, at least outside the country. Gradually, through the Seventies, he acquired the TV rights to all the races. This enabled him to reach an agreement with broadcasters for them to show the entire championship. This allowed him to build up the largest possible audience and obtain the widest possible TV coverage. As a result, the TV rights gradually became valuable. By the time the first Concorde Agreement was signed in 1981, Bernie had acquired the TV rights to virtually every Grand Prix."

Max's memorandum to the heads of FIA automobile club federations as to the danger of the European Arrest Warrant (EAW) legislation (2004):

Max's memorandum to the heads of FIA automobile club federations as to the danger of the European Arrest Warrant (EAW) legislation (2004):

"I never answered the other question about the memoir: I've got no plans to write a memoir."

"I never answered the other question about the memoir: I've got no plans to write a memoir."

From dinghy garages in Oxfordshire to the Oxford Union, and from the great race tracks of the world where he drove next to Jim Clark, to the corridors of power at Place de la Concorde and 10 Downing Street as FIA President, it has been quite a ride for the retiring Max Mosley. But even so, Max, in some ways, we hardly knew ye; best of luck at the beach with a book.

|

Contact the Author Contact the Editor |

Please Contact Us for permission to republish this or any other material from Atlas F1.