Atlas F1 Technical Writer

New regulations, controversial innovations, required reliability, surprising design solutions and challenging locations - 2004 offered plenty of material for Atlas F1's technical guru Craig Scarborough, as he reviews the mechanism of Formula One's longest season in history

Rule changes

New rules for 2004 had no meaningful effect on the design of the cars. Technical rule changes revolved around reducing the rear wing to only two upper elements, while engines were expected to last the full Grand Prix weekend or suffer losing ten places on the grid. Also of some importance - though indirectly related to the technical aspect of the sport - were the changes to the qualifying format and allowing the bottom six teams to run third drivers on Friday.

The rear wing changes basically limited how steep a wing could be run before it stalled, and as a result limited downforce. However, teams soon regained the 5% of lost downforce and then increased it again by the season's end. Furthermore, fussy changes to the rear wing endplate and engine cover had little effect on performance, and the new dimensional regulations only benefited the marketing departments and posed no major problems for the technical departments.

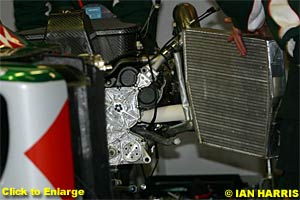

Engine changes were also expected to have a radical effect, yet by and large the changes had limited effect. Before the season's start, most manufacturers had engines on a par with their 2003 units and with the requisite 800kms lifespan. At first, many teams chose to reduce revs on Friday and late in the race. By mid season, however, development had fully caught up and outputs and rev ceilings were escalating once more. Honda quoted outputs of 960bhp for their Suzuka-spec engine - over 40bhp up on 2003's maximum (reached by BMW) and with twice the lifespan.

Related to the engine changes were imposition of control system changes, starting with a ban on fully automated shifts and launch control. At first the up-shift issue saw drivers several milliseconds off the optimum, but soon they were hitting the changes at remarkable accuracy. Launch control was also a simple hoop for the teams to jump through. The rules limited what could be controlled via the feedback from sensors during the launch phase.

However, as with most banned driver aids, the new non-active solutions derived from the knowledge gathered while developing the active solutions. So while the teams weren't able to adjust clutch, throttle or ignition during the launch, they were able to program it in advance to carry out the most efficient predicted launch. Renault, as ever, had the best solution - their use of mechanical and electronic solutions gelled so well, that they were often positions ahead by the first corner.

Some teams did suffer problems - Toyota and Jaguar in particular, but also Williams. Curiously, Ferrari never had a problem but also never actually made up ground at the starts, and launch control could be considered the team's weak point in 2004.

Weekend changes moved qualifying to back-to-back sessions, allowing refuelling after the first session to get the car up to its race fuel load. The change did limit the time teams had to prepare the car before the crucial qualifying session, but only in the event of crashes or blow ups did the format provide any real issues for the teams.

The running of third drivers in Friday's practice sessions had little effect on the teams at the back of the grid, but up front BAR were able to make the most of their extra car and used Anthony Davidson for extensive tyre testing and running of new parts. Just as importantly, Davidson was able to run full revs and many new tyre sets, often topping the time sheets when the other top five teams were minding their revs and tyre allocation.

Development in 2004

In response to the new rules, and as part of a more general development path, 2004 saw great many innovations. While some were generally adapted, several were cheeky interpretations of the rules and following some FIA clarifications some of these were dropped.

Wing fences

BAR, followed by other teams, realised they could fence off the different wing sections to create smaller vortices from more intersections. However, soon enough the FIA intervened when news of a "chip cutter" wing was tested by BAR, using twenty fences.

A clarification was released as to what constituted a wing cross section. In an attempt to retain their fences by bending the wording of the rules, Jaguar produced two overlapping fences to effectively create one large fence. This went too far and the FIA further clarified how much larger than the main wing profile these fences could be. The teams relented and no further attempts were made at fencing the differing pressure zones.

Rear wing endplates

Along with the restriction on wing elements, the larger rear wing endplate (RWEP) was at first adopted uncomplicatedly by the teams, with some teams opted to make a notch behind the rear wing flap. Minardi were the only team to place a vertical slot in the endplate to allow the wake of the wing to form something like it had with the smaller RWEPs. Soon Renault adopted this design and latterly Williams too.

Shelf wing and mid wings

The shelf wing, which is a low wide wing mounted ahead of the rear wheels, and the mid wing - mounted high on the roll bar - were both designed to shape and improve the flow to the rear wing. These were also termed "Type R" wings by BAR, in deference to the "Boy Racer" wings added to Honda road cars. Although the "Wings" were of aerofoil cross section, they often point downward as if to produce lift.

The inverted approach actually directed the largely horizontal flow over the car downwards in approach to the rear wing, effectively making the wing 'think' it's steeper. They also served to smooth the flow from the various devices disturbing the airflow as it passes over the car. The cleaner flow prevented the flow separating under the wing when set at high downforce angles and causing undue drag.

Angled chimneys

Sprouting from the shoulder of the sidepod, a tapering chimney angles out to the maximum permitted width and height, leaving its exit slashed vertically. This device both acts to draw heat out of the sidepods and send it into the accelerated flow of the following winglet, as well as act like a turning vane, pointing general flow around the sidepod. Hence they were often run even when the weather was cool, simply blanking off the exit, in order to retain the turning vane effect.

FTT

The system was an unnecessary complication to a team rebuilding after the loss of its driver and technical staff to Ferrari (Michael Schumacher, Ross Brawn, and Rory Byrne). And, driven by Alex Wurz and Giancarlo Fisichella, it was only the latter that made good use of the system. It was therefore dropped by mid season, and the idea was never revived as many believed the wording of the regulations prevented its return.

BAR's designer Geoff Willis was once considered a conservative, but his response to the taking the technical helm at BAR has revealed he can be a non-conformist quite often. At the BAR 006 launch, Willis mentioned that F1 cars are basically limited by corner entry stability, as a result of getting the braking, turning and resulting weight shift completed within the grip available. Unknown to his listening crowd back then, Willis was in fact hinting that his technical team had found a potential way of recouping some extra stability, and it transpired that the FTT system was the solution.

BAR's solution debuted at a Jerez test and then at the German Grand Prix. Initially the system appeared similar in concept to Benetton's, with drive shafts linking the wheels to a central differential mounted in the nose. But the advance BAR had made was to add electronic control that manages the differential via hydraulics. Given the title 'Front Clutch Pack' (FCP) by BAR, the system was run on Friday and with the FIA's prior knowledge. BAR felt little risk was involved, however other teams complained to the and BAR was forced to withdraw the device, also losing an appeal on its ban.

Bar were back at the drawing board and by Monza they had a system without the electronics and raced with the approval of the FIA. McLaren, at least, were still not happy, but by the time the teams arrived at Brazil and in a conciliatory mood, Willis relented and stated the system would not run again on the car.

Carbon Gearbox

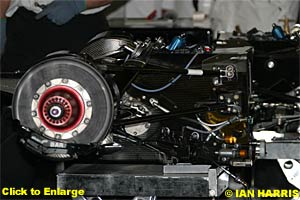

While this had been done before by both Stewart and Arrows, only one had been retained, with Arrows running carbon cases up until the team's demise. McLaren had included a carbon case in their stillborn MP4-18 program, with the case creating one of the problems in the car. But with engineer Gary Savage - previously with Arrows and now with BAR - the team were able to develop a case and have it running reliably in the rear of the testing "concept" car over the winter.

Having a lighter case offers many benefits. Firstly, the static weight of the car is lower, allowing weight to be added elsewhere, for example in the form of ballast. Secondly, less weight at a car's extremities decreases its inertia, increasing its rate of turn for a given input. Lastly, the production of the gearbox can be brought in-house, while castings still need to be farmed to specialist manufacturers - although the Carbon department would still need the experts and resources for a highly complex product. Willis also says that the ease of repair was another unexpected benefit, as the team's mobile carbon workshop allowed them to patch a broken case overnight in order to continue testing the next day.

What Savage has achieved is the accurate mating of carbon fibre with the metal internal bulkheads that mount the gearshafts. These need to be stiff and expand at the same rate under the heat generated by the gears. This was the fundamental drawback of the early carbon cases, the rate of thermal expansion for carbon differs from metals, leading to the bonded joints cracking and offsetting the gearshaft bearings, wrecking the gearbox. Detail work has alleviated these problems and left BAR with an advantage over the opposition.

Team by team

Ferrari

The hooked nose, reaching down towards the wing, dictated a design of flatter wings with flicked-up outer chords. A late season move to a curved middle section followed the theory, plus there were variations on the trailing edge shape and occasionally a serrated gurney was adopted. Endplates used Toyota-like double flip ups and wavy footplate, seeing just one revision during the year.

Double panel bargeboards adopted several horizontal splitters around the suspension and dog legged lower edges to keep the flow nearest the ground, pointing along the underbody step. Behind the boards was a shark fin to manage the flow off the shadow plate and under/around the sidepods. The trademark undercut sidepod leading edges were shaped around slanted radiators and projecting exhausts. A single large flip up remained throughout the year, as did the detail fairing around the gearbox. Cooling was originally with grills, but Ferrari switched for chimneys by mid season.

To the rear, Ferrari used simple endplates and a slight curvature of the rear wing edges. A diffuser that uniquely used two fences in the outer tunnels was copied by Sauber, but otherwise remained as per the original concept. Rear brake ducts also followed a similar path throughout the year, both front and rear brakes using donut fairings at most tracks.

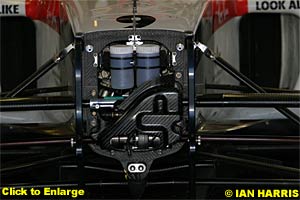

Front suspension used a single keel, which kept the wheels with some camber and inclined upper wishbones. The third damper was mounted above the rocker linkage to allow easy access through the top of the chassis at the expense of the Centre of Gravity. At the rear, the Sachs rotary dampers seen in 2003 were maintained, with the installation tidied into a recess in the gearbox. The Titanium gearbox boasted some carbon reinforcement, but was never visible externally, so perhaps it was placed internally. Using seven speeds, the unit was still short and low.

Although the team admitted to using over-heavy components - like the base of the monocoque and the sump - a large amount of ballast was housed in the detachable shadow plate.

The engine was a logical development of the 2003 unit, sporting a 90-degree V-angle. The unit managed to up its output and retain its reliability through the one-engine-per-weekend rule. Modestly powering the chassis, the Ferrari engine is rarely regarded as the most powerful engine, but it surely ranks equal with any of its competitors on size, drivability and output. Full power engine settings were not always used and one source suggests the card was on its full settings only at Monza.

Chassis-wise, the car was shorter and less prone to understeer than the F2003-GA. Hence, the car suited Michael Schumacher better than it suited his teammate, Rubens Barrichello. The Brazilian also reverted to right-foot braking, but still used two pedals, as the clutch was on the steering wheel. Barrichello was able to shine at flowing tracks that flattered his driving style, namely in Spain, Brazil and Japan.

Start line performance was a notable weak point for Ferrari, often jumped by BAR, Williams and of course Renaults. However, this may not be a function of Ferrari's traction or power, but the level of fuel they were able to start with. Elsewhere on the track, traction and acceleration was fine and straight line speed amongst the fastest.

Managing the new blend of Bridgestone tyres, catapulted the team from only dark horses during pre-season testing to unbeatable by the end of the season's three opening flyaway races.

Over the winter, Bridgestone ran a two pronged assault on tyre development, one group looking at compounds while the other worked on a wider front tyre in close conjunction with Ferrari (not only for the chassis but for aerodynamic reasons, too). In fact, Bridgestone only amalgamated their tyre compound and construction programmes in the immediate run up to Melbourne.

The resulting tyres reversed their character over 2003, now appearing more durable over the course of a stint, while more sensitive to load, heat and track surface. They often required several laps to warm through, despite being the fastest on dusty tracks at the first practice on Friday mornings. This made opening laps tricky. Ferrari's clutch of pole positions were a result of lighter fuel and lesser fuel loads to safeguard the lead in order for the tyre's upturn in performance - at around laps 3-5 - to be realised on a clear track.

The fuel load of Shell's "light fuel" contributed largely to Ferrari's surprising pace in the opening races. Where Michael Schumacher often lost the lead from fast starting rivals, He was then able to follow the car to the first stop, then run more laps to make enough of an advantage to open up to retake the lead. When the pole position was in the hands of a Michelin runner, the warm-up lap was often run especially slow to hinder the Ferraris from getting their tyres up to temperature, and equally the safety car periods at Spa hindered the tyres' performance. Extraordinarily, tyre degradation under pressure forced Ferrari into a four stopper for Michael in France.

In the wet, the Bridgestones were superior, but at the cost of damp tracks not suiting the dry tyres and forcing the use of intermediates, which would require changing regardless of weather improving or worsening. Also, Monaco didn't suit the Ferrari, with hot weather preventing the soft Bridgestone tyre from lasting long. Safety car periods also cost Ferrari at Spa and Silverstone.

BAR

Although BAR developed a very different car to the 005 and ran some highly innovative solutions through the year, they outwardly appeared to change the least. In fact, they did not have a major aero upgrade during the season, only a revision to the cooling options and detail work around the wings. This suggests the team's neat and simple aero solution worked well and was matched to good tyres and chassis. Considering BAR have a relatively simple wind tunnel - built by Reynard for the team when it first started up - the quality of the aero work is testament to their design process.

The car's main aerodynamic features are curved front wings mounted to a conventional nose that retains a good ground clearance all the way back to the driver's hips. This was one area the car made gains over the 005. Nestling in between the front suspension were two simple aero devices, a pair of small turning vanes and horizontal fin with the flicked up tip to produce a vortex to condition the flow instead of a further turning vane. Still adopting the horizontal fin ahead of the square shouldered sidepods, the coke bottle shape tucked in closely albeit obscured by the ugly cooling outlets and winglets.

These devices were mounted to a detachable panel and were frequently swapped for closed or asymmetric set-ups, depending on conditions. The rear wing was preceded by varying sizes of mid wing and an optional shelf wing. A combination of pinched-in endplates and fences (until the clarification) were simple solutions to the pressure difference at the wing tip.

While the large part of the aerodynamic setup remained the same, the front wing endplates were - as Willis predicted at the start of the season - an area for great development. The original endplates were simply shaped, and through the year they adopted variation on dive planes and footplates seen in use by other teams. BAR were developing the designs to this extent as they learned how the Michelin tyres deflected and affected the flow off the front wing.

The new gearbox did provide some problems for the team, but largely confined to the third car or in practice for the race drivers. With the carbon fibre cased gearbox grabbing the headlines on the mechanical front, the Honda manufactured internals and the adoption of Alcon brakes were much overlooked and highlighted the extent to which BAR ignored convention to gain advantages.

On top of the gear case was a much tidier damper arrangement than in 2003 - the dampers and rockers now much smaller and sunken into the top of the casing. All the detail work to lighten the car also had to go into where the ballast could be placed, and BAR used large slabs of metal under the shadow plate, requiring a redesign after some went stray on Takuma Sato's car over kerbs.

BAR also went a very different direction on their suspension's camber settings to other Michelin runners, and their use of the tyres across all types of circuit proves they had found some benefit. However, the drivers often cited, post-races, a lack of grip from earlier in the weekend, which may have been the downside of the camber.

Matching BAR's improved form was Honda, also working on the chassis and transmission side nowadays, but the progress they made with the engine over maligned units used only a few seasons ago has been striking. Honda admitted at the start of the season their engine was ahead on power and weight than their shorter lifed 2003 unit. While this was arguably true, the reliability of the unit was still suspect throughout the year, with Sato suffering repeated failures earlier in the season.

Renault

The sidepods, wings and bargeboards have all taken a curved and sculpted shape, aimed at making every surface on the car work to its best possible aerodynamic performance. While other teams would adopt a straight-line or a simple cross section, Renault twisted every profile to meet the differing flow along every inch of its length.

This approach was very impressive, and the figures coming out of the windtunnel showed a real improvement over the R23, but this was offset with a greater sensitivity which didn't show up in simulations or windtunnel results. The drivers soon found the car was fast but difficult to set up in the sweet spot that released that speed. The engine was still some way from competitiveness at Melbourne; down on revs compared to the rest of the field, the engine department's progress under the eye of Rob White was immense, raising the engines revs by over 1000rpm and a reputed 80bhp. Overall reliability was still not good, with two engine problems in

practice, two oil related failures causing retirements, and the pair of driveshaft problems in Canada.

Combined with the relatively heavy engine was the new gearbox. Now produced in titanium, the casing was no longer using a lightweight part carbon fibre casing, and was believed to use a larger clutch. These differences raised the belief that Renault used a more rearwards weight bias than other teams, and the differing weight distribution meant Renault had different Michelin tyres to other teams.

Some people have suggested that this was in order to improve their starts; it's unlikely that Renault chose to do this, as the cost would be sacrificing speed over a full lap. It is also unlikely this was because the engine and gearbox were too heavy. The difference in static weight distribution may only be 1% (6kg), and around 8% of the car's ballast; moving this around the car to correct a heavy engine would not be difficult. It seems that Renault have simply found a way of extracting a lap time from the tyres in a different way to other teams.

Launch control may have been banned, but Renault was top of the fast starters for most of the season. A rearwards weight distribution no doubt helped, as would the method of setting the clutch biting point and releasing the clutch from that position at the start. Rumours suggested the clutch strained against the brakes until the clutch was let go and the brakes released, meaning the car was on the move the instant the driver initiates the start. Lastly, the rival teams pointed out the car fully released its clutch at low revs, using the engines less peaky power delivery to pull the car forwards with less chance of wheel spin.

The car's traction, whether mechanical or electronic, also helped the team on faster circuits, where their lower powered engine may have impeded their pace. Often we saw the Renaults gain such good traction and acceleration out of corners preceding a straight; even a much faster following car could not make up the deficit by the end of the straight.

McLaren

By Malaysia a new front wing had appeared, along with a number of holes in the sidepods to keep the engine cool; while their pace improved the engine repeatedly failed for Kimi Raikkonen in the early races. The team announced a B spec car for mid season; this arrived later than expected, debuting in France. The revised chassis, aero and engine made a real difference, and soon the team were moving towards the front of the grid.

Technical worries continued due to marginal cooling and a worrying wing failure for Raikkonen, leading to more race retirements. Throughout the year he made best of the cars difficult handling, but David Coulthard never found it to his liking and was unable to drive around the problem as Raikkonen had. Coulthard's late season weekends involved too many incidents while recovering from midfield qualifying slots, while Raikkonen was able to take a win aided by the changing conditions at Spa, showing the progress made during the year.

Williams

In deciding on the development intensive nose and twin keel set up, the team took its eye off the ball on other areas; the FW26 did not push any boundaries or even meet the standards set by other teams. The sidepods and rear aerodynamics were largely intact from the FW25, the short six-speed gearbox grew another gear without getting any longer, and novel damper linkage arrangement were departures from the 2003 philosophies.

Already well discussed, the twin tusk nose and twin keels provided aerodynamic gains and allowed a new direction in the way the flow from the wing works with the turning vanes. But the cost of this gain was weight, with the shorter nose needing to be heavier to absorb the load, and the twin keels also needing to be heavier to prevent deflection. Combined, the mechanical problems of the nose were tied to a specific wing shape, but when the team looked for more downforce in a newly shaped wing it worked better with the conventional nose adopted from Hungary.

As well as the nose issue there were problems around the rest of the car. The aerodynamics went through an intensive race-by-race development programme, the production facilities at Williams were flat out producing the new sidepod wings, noses and floors seen from France through to Suzuka. Williams worked on mechanical systems too; the new gearbox was too close to the edge, leading to failures in three races. As with other work around the car, the solution was only partly a cure, ideally requiring a new gearbox, which the team couldn't produce in-season.

By the end of the season the technical team had revised everything they could and the car was very much on the pace; the cost of this work was the load on the team's resources and the windtunnel. As the new tunnel is not yet producing production parts, the sole tunnel needed to be split between the FW26 and the late starting FW27 programme. With the very different aero rules for 2005 the development work on one car could not be switched to the other.

Sauber

After a poor season in 2003, where aerodynamic revelations found in a commercial windtunnel came too late to improve their season, their new windtunnel came on line and allowed the new car to be developed a state of the art facility. The difference was visible. The new car bore a strong resemblance the outgoing Ferrari F2003, from which it took its engine and gearbox. While rumours abounded of how much input Ferrari provided into the car's external surfaces, Sauber were resolute in stating it was all their own work. Some parts, like the radiator layout, were novel and not from Ferrari's design book; the book folded radiators creating larger coolers in a tighter space, and were unique. In the early season the car had a new power steering system developed, which was long overdue for the tired arms of Giancarlo Fisichella.

At first the car was nervous to drive and didn't make the best of its engine or tyres. By mid season new aero parts were appearing with revised winglets, exhaust fairings and a shelf wing, but still race incidents and tyre performance were hindering the team. At Silverstone the team rolled out their new bodywork; this was a massive step forward for the team, with extremely waisted sidepods designed to make the most of the book fold radiators and improve flow to the rear.

With this came better aerodynamic efficiency, and soon the team were running more competitively, gaining points finishes, but were still hindered by graining tyres and race incidents. The team's struggle for tyre competitiveness shaped their weekend strategy, often qualifying well and running aggressively for the first stint in the race before fading away as they nursed their tyres. Reliability was not on a par with Ferrari; the team suffering three engine failures and several delayed pitstops from clutch problems.

Jaguar

While the car showed pace in qualifying the team's inability to get the Pi research developed launch system working stymied any progress in the opening races. Many straight line tests were carried out to cure the problems, diverting their attention from improving the chassis.

Even up to mid season poor starts and detail retirement issues caused by electrics and hydraulics, as well as crashes, kept the team from the points. Some new parts were appearing; the banned rear wing fences, revised winglets and vertical struts supporting the flip ups for example, but they were not major upgrades.

By mid season a Cosworth upgrade meant the cars were at least running reliably to the finish. For the last few races, and timed with the teams ‘for sale' notice, a new lighter monocoque was produced, with each driver taking it in turns to race the design to little noticeable effect. Overall the car lacked the qualifying pace it had shown in 2003 but had improved, if not eradicated, it hunger for eating tyres.

Toyota

Gascoyne soon assessed the team's resources and the car's shortcomings, and set about a reorganisation of staff as well as the details on the car. Taking technical control of the current car, he placed designer Gustav Brunner into a new car development role, one is much more suited to. He also took over the aerodynamic team, relegating Rene Hilhorst to other projects. The car's development was ongoing but not visible in the first part of the season as Gascoyne worked on two upgrades, one of which was for the chassis which he felt was too heavy and placed its weight up too high.

The second project for was for the aerodynamics to be introduced after the new chassis broke cover. Race weekends were marred by minor technical problems, communications problems and a lack of grip generated by the Michelins. Olivier Panis also seemed to suffer with start line problems more than Cristiano da Matta. The German race introduced the new specification aero and chassis; no immediate benefit was gained, and Panis again had a start line clutch problem.

Complicating the team's situation was the firing of da Matta and drafting in of Ricardo Zonta to race a car he had yet to test; later in the season more disruption was brought when Jarno Trulli replaced both Zonta and Panis at different races. Towards the season's end the team found some pace; in China as the conditions suited the Michelins, but again Panis suffered start line technical problems and Zonta was to retire form transmission problems. Detail development continued with revised front wing endplates, but the car still lacked downforce and never worked well over the bumps or with its tyres.

Beneath all these problems was the engine which Toyota confidently announced was ready to run for 800 km by the end of the 2003 season; it went unnoticed. The team needing to run a lot of wing to help the handling, which meant the engine wasn't able to show the top speed it could produce. Few people mentioned its prodigious power and reliability; this perhaps was the one good component Toyota produced in 2004.

Jordan

Development moved slowly; detail changes to the endplates on the flip ups and new winglets were the sole variations. Mid season saw the team introduce the shoulder wings; placed level with the front of the sidepods, these devices may have added a little downforce but probably only served to improve the flow over and around the sidepods. Only a Monza aero spec, created by removing most of the extra aero devices, changed the cars for the balance of the year, with the team struggling with power steering, gearbox problems and poor grip from their tyres. By season end some points were scored, but the team was firmly stuck between Minardi and the rest of the pack. Their future is uncertain with the sale of Cosworth; rumours of an engine supply deal with Toyota continue, but how they are going pay for this deal is unclear.

Minardi

Throughout the season revisions to the front of the sidepods and the addition of mid and shelf wings were the only technical novelties. Reliability wise the team were struggling, with over ten engine failures/changes and no less than three at Silverstone. Brake and gearbox problems lost the team track time, as did a errant wheel which fell off as well as pit lane incidents, including a pit fire and a couple of mechanics being run over. On pace the team were at the very back of the grid, occasionally joined by a Jordan or Jaguar. With the departure of Cosworth likely the team have earmarked the European V10 engines derived from older Cosworth units, last used in 2001, for next season.

After the longest season in Formula One History, with 18 Grands Prix, the teams produced a long list of new developments - both reacting to the new rules and as part of their long term development plans. Many teams had to overcome a poor initial design with at least four "B" spec cars; equally, some teams didn't have the financial security to develop their packages. Leading the grid by a comfortable margin was Ferrari with a conservative development of the 2003 car, but with the aid of reliability and excellent tyres, they were able to win the Championships at an early stage. The other two teams usually at the top of the grid, Williams and McLaren, struggled and allowed the two younger teams of BAR and Renault to sneak into second and third places in the Championships.

While the teams were forced to find more downforce from simpler (two element) wings, they also wanted to keep a cap on Drag. In 2003, deeper middle chords and shallower outer chords allowed the wing to create downforce without the strong drag-inducing vortices that get created from the wingtips.

While the teams were forced to find more downforce from simpler (two element) wings, they also wanted to keep a cap on Drag. In 2003, deeper middle chords and shallower outer chords allowed the wing to create downforce without the strong drag-inducing vortices that get created from the wingtips.

The rear wing's effectiveness largely depends on how good the flow approaching it is. With the rear wing working in close co-operation with the flow from the diffuser and lower wing beam, any improvement to the flow is multiplied. Ferrari and BAR were quick to adopt solutions seen in 2000 (when the rear wing was last trimmed).

The rear wing's effectiveness largely depends on how good the flow approaching it is. With the rear wing working in close co-operation with the flow from the diffuser and lower wing beam, any improvement to the flow is multiplied. Ferrari and BAR were quick to adopt solutions seen in 2000 (when the rear wing was last trimmed).

Cooling solutions tend to follow fashions, and the chimney has been out of favour for a few seasons, replaced by grills. This year, however, a new variation appeared, based on Renault's diverging tapered chimney, and the new setup was adopted by Ferrari, Williams and later Toyota.

Cooling solutions tend to follow fashions, and the chimney has been out of favour for a few seasons, replaced by grills. This year, however, a new variation appeared, based on Renault's diverging tapered chimney, and the new setup was adopted by Ferrari, Williams and later Toyota.

Back in 1999, Benetton (Now Renault) adopted a device linking the front wheels in order to produce a more balanced braking effect. The system, dubbed Front Torque Transfer (FTT) by Benetton, was based around a heavy differential unit driven by drive shafts in between the front wheels. When the inner wheel unloaded into a corner, the outer wheel would drive that wheel, preventing locking.

Back in 1999, Benetton (Now Renault) adopted a device linking the front wheels in order to produce a more balanced braking effect. The system, dubbed Front Torque Transfer (FTT) by Benetton, was based around a heavy differential unit driven by drive shafts in between the front wheels. When the inner wheel unloaded into a corner, the outer wheel would drive that wheel, preventing locking.

With BAR in an innovative frame of mind when planning for 2004, they were also able to produce a unique (in current F1) gearbox casing. With the aim of removing weight from the rear extremity of the car, a gearbox casing was manufactured in carbon fibre.

With BAR in an innovative frame of mind when planning for 2004, they were also able to produce a unique (in current F1) gearbox casing. With the aim of removing weight from the rear extremity of the car, a gearbox casing was manufactured in carbon fibre.

The team's rate of development throughout the season was actually quite low, but not from a negative point of view. The F2004 was easily beating its rivals, so development was light - only the sidepod cooling and wings had major changes, also with detail modifications to the front wing endplates and barge boards.

The team's rate of development throughout the season was actually quite low, but not from a negative point of view. The F2004 was easily beating its rivals, so development was light - only the sidepod cooling and wings had major changes, also with detail modifications to the front wing endplates and barge boards.

With the change in technical management and the success 2003 brought, there was a buoyant mood around the team at the 2004 launch. Renault had turned on its heels and dropped the wide angle engine, producing a new, narrow angle unit for the one-engine-per-weekend rules. The resultant car was based on a highly complex aerodynamic philosophy; rather than the radical approach Williams attempted, Renault adopted a level of detail and optimisation, making the shape of every part of the car extreme.

With the change in technical management and the success 2003 brought, there was a buoyant mood around the team at the 2004 launch. Renault had turned on its heels and dropped the wide angle engine, producing a new, narrow angle unit for the one-engine-per-weekend rules. The resultant car was based on a highly complex aerodynamic philosophy; rather than the radical approach Williams attempted, Renault adopted a level of detail and optimisation, making the shape of every part of the car extreme.

As a team that challenged for wins in 2003 and had their 2004 car ready by the end of 2003, McLaren looked set to threaten for a Championship win. Early testing backed up this theory, with long, reliable and fast runs being completed. However, in the new year the new engine went into the car and everything changed; the team failed to get the car to run quickly or for long enough, optimism turned to worry, and as the season started the team were in dire straits, having the engine detuned for reliability and major new body panels in development.

As a team that challenged for wins in 2003 and had their 2004 car ready by the end of 2003, McLaren looked set to threaten for a Championship win. Early testing backed up this theory, with long, reliable and fast runs being completed. However, in the new year the new engine went into the car and everything changed; the team failed to get the car to run quickly or for long enough, optimism turned to worry, and as the season started the team were in dire straits, having the engine detuned for reliability and major new body panels in development.

At the season's start everyone gasped at the dramatic nose adopted by the Williams, who were better known for their conservatism in recent years. The optimism shown by the team and the resultant media excitement was soon overshadowed in testing, and by the end of the first race it was clear that the car, while not a failure, was certainly lacking in pace to match the other Michelin runners, let alone Ferrari.

At the season's start everyone gasped at the dramatic nose adopted by the Williams, who were better known for their conservatism in recent years. The optimism shown by the team and the resultant media excitement was soon overshadowed in testing, and by the end of the first race it was clear that the car, while not a failure, was certainly lacking in pace to match the other Michelin runners, let alone Ferrari.

After a troublesome season with tyre wear issues in 2003, Jaguar only changed parts on the new car that were proven to improve their old chassis; the resultant car was largely based on the same dated philosophies as the R5. Installed in the car was a new version of the 90-degree Ford engine, which embarrassingly failing at its launch, setting the tone for the remainder of the season.

After a troublesome season with tyre wear issues in 2003, Jaguar only changed parts on the new car that were proven to improve their old chassis; the resultant car was largely based on the same dated philosophies as the R5. Installed in the car was a new version of the 90-degree Ford engine, which embarrassingly failing at its launch, setting the tone for the remainder of the season.

Mike Gascoyne, who joined the team late in 2003, was too late to influence the cars design for 2004, but the TF104 was a modern looking car with all the right shapes seen on the other teams' new cars. The expectation was that Toyota would finally realise their potential, but early testing again proved the car was not up to the job.

Mike Gascoyne, who joined the team late in 2003, was too late to influence the cars design for 2004, but the TF104 was a modern looking car with all the right shapes seen on the other teams' new cars. The expectation was that Toyota would finally realise their potential, but early testing again proved the car was not up to the job.

The team, clearly struggling with little cash, made the most of its resources and produced a new car for 2004. The EJ14 eschewed the twin keel designs of Gary Anderson, adopting a more pragmatic single keel, saving weight and expense in the process. While the front end structure was very different the rest of the aerodynamic philosophy was carried over from the previous year; the team was unable to afford the level of windtunnel time to find new solutions. Now using the Cosworth CR6 90-degree engine, Jordan had parity with Jaguar and a decent engine. They mounted its exhausts in a unique style, spaced out wide from the cars centreline.

The team, clearly struggling with little cash, made the most of its resources and produced a new car for 2004. The EJ14 eschewed the twin keel designs of Gary Anderson, adopting a more pragmatic single keel, saving weight and expense in the process. While the front end structure was very different the rest of the aerodynamic philosophy was carried over from the previous year; the team was unable to afford the level of windtunnel time to find new solutions. Now using the Cosworth CR6 90-degree engine, Jordan had parity with Jaguar and a decent engine. They mounted its exhausts in a unique style, spaced out wide from the cars centreline.

Minardi produced another update of their PS02 car, re-developed in 2003 and now once more revised to suit the new engine and differing aero rules. Cosworth supplied the CR3-L engine, a reworking of the old 72-degree engine the team had run in 2003. Otherwise the car was unchanged, with familiar sidepods and the once innovative Titanium gearbox.

Minardi produced another update of their PS02 car, re-developed in 2003 and now once more revised to suit the new engine and differing aero rules. Cosworth supplied the CR3-L engine, a reworking of the old 72-degree engine the team had run in 2003. Otherwise the car was unchanged, with familiar sidepods and the once innovative Titanium gearbox.

|

Contact the Author Contact the Editor |

Please Contact Us for permission to republish this or any other material from Atlas F1.

|

Volume 10, Issue 44

2004 Season Review

The Atlas F1 Top Ten

2004 Race-by-Race Review

2004 Drivers Review

2004 Teams Review

2004 Technical Review

Bjorn Wirdheim: Going Places

2004 Qualifying Differentials

Columns

On the Road

Elsewhere in Racing

> Homepage |