Atlas F1 Technical Writer

After three years in Formula One and with technical director Mike Gascoyne fully behind their 2005 car, Toyota Racing face crunch time this season. The TF105 must perform - and the Japanese owned, cologne-based outfit spared no efforts in the design process. Craig Scarborough attended the Toyota launch at Barcelona last weekend and spoke to Gascoyne and the technical staff. He offers a full analysis of the changes and features of the new car

Toyota in 2004

Last year was not a step forward for Toyota on track; the car lacked speed, and this compromise in reliability lead to too many midfield incidents forcing retirements. Engine reliability was very good, with a single failure at Spa during the Belgian Grand Prix - put down to an unforeseeable early failure of an otherwise reliable part.

On a positive note for the team, new technical director Gascoyne, fresh from his success at Renault, was onboard. He was, however, too late to influence the TF104's design and soon set about a "B” spec car - the project team initially meeting even before the first race in Melbourne. Gascoyne had pinpointed failings in most areas of the chassis, from aero to suspension and the structures. Without time to redo the whole chassis, an aero step and rebuilt monocoque were the changes possible in the timescales.

The TF104B debuted in July, with a much lighter monocoque and revised wings and sidepods. These changes provided the increase in downforce and lower centre of gravity essential to improve the car's performance. Left uncompleted were the suspension and gearbox - the former in particular was again an Achilles heel of the car.

Heading into the development of the new car, the mechanical elements would come in for more scrutiny while aerodynamics is a never ending avenue of development, especially with the new rules introduced for 2005.

New Approach

In both mechanical and aero departments, the car lacked the detail work to bring a concept up to speed with a series of small steps. As Gascoyne told Atlas F1: "it's my job as technical director is to prioritise what you do, and sometimes you can make bigger gains from changing less bits.”

As an example, the rear suspensions failings were analysed to understand where the problem was, as Gascoyne explain: "the rear has changed significantly. We did a lot of testing on the test rigs and identified areas where it needed to be significantly improved. We did some good scientific investigation of it - rather than redesign everything and hope. We understood where the problems were and this allows us to fix in detail.”

In the windtunnel, the search for big gains, which were needed to improve the car's pace, was masking the more numerous smaller gains that would have reaped the same reward. "It was inaccurate, it wasn't methodical, and it wasn't down to the required level of accuracy and repeatability," Gascoyne summarises the wind tunnel's procedural faults.

"This meant that you lost a lot of things that would have given us small improvements, and the overall improvement rate wasn't good enough. They were looking for big steps to catch up, but big steps come from lots of small steps. It took us six to nine months to do that - to have a tool that I felt was capable of developing as the top teams do.

"The frustration of doing this work is that while you are doing it, you are not catching them up. Which is why when the regulations came along, for us it was a great opportunity, as it does level the playing field and also it meant we could make the easy decision to say forget the TF104 and concentrate on the TF105.”

Equally, Gascoyne's approach to releasing a new car sees an approach previously adopted at Renault resurface: namely, releasing a mechanical package early with interim aerodynamics, then updating the aero before the first race.

Once the conceptual work was done on the aerodynamics, it proved the moving of the front bulkhead wasn't necessary and that the old nose cone/front wing assembly would suffice for interim testing. These parts were frozen to allow the designers to focus on other areas. Also, with the monocoques structure receiving attention during the TF104B project, little work was necessary to make additional gains. So it was the priority areas of aerodynamics and mechanical set-up that received the most development.

There have been some winners and some casualties in this process; the previous head of aerodynamics, Rene Hilhorst, has left the team. On the other hand, Gustav Brunner – who was previously juggling designer and director roles, along with engineering the car at the track during the team's infancy – is now able to focus his energies on future development, heading the rework to the TF104 and conceptual work on the TF105.

Perhaps the unsung and biggest winner in all this is the engine department; headed by ex-Ferrari man Luca Marmorini, the department has produced an engine with excellent power and driveability, with the reliability record to match Ferrari. His department has been working effectively to produce these competitive engines only to be hindered by an unwilling chassis. Should the Gascoyne influence correct this situation, the team have an excellent base to realise their potential.

Aerodynamics

A caveat to the car's aerodynamics is that they are only interim versions - the nosecone, wings and sidepods will change before Melbourne. The Melbourne changes are described as "substantial” but will probably not be radically different in concept to what's seen on the interim car. As mentioned, the nose cone and front wing are from the TF104, with just the mounting pillars being shortened to meet the new regulations. And, since the front bulkhead has not been raised, the nose is not higher than the T104's.

"Aerodynamically, I don't think it's fundamentally changed," Gascoyne comments. "There are detail changes due to the new downforce regulations”

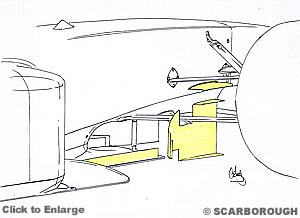

The car retains a neat single keel and the area under the monocoque has been raised slightly to meet the dimensional regulations. Again, the bargeboards are interim items matched to the front wing, but they follow a BAR design of a small simple board and horizontal fin between the wishbones.

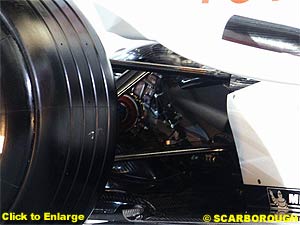

The exhaust outlets are placed very close to the centre line and are quite low firing up underneath the rear wing. The upper part of the engine cover is also much narrower, now requiring a bulge to clear the airbox, but the neater damper installation has removed the large blister to cover the third damper.

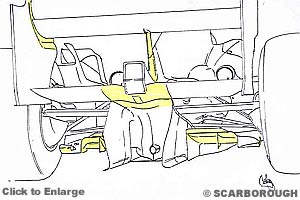

The rear wing itself must be close to the final production item, as this is the most unconventional item on the car. Gascoyne believes this may be a common sight in 2005, stating: "with the elements moving forward, the interaction between the lower wing and the top wing changes - in fact the car's lower beam is very three dimensional shape and sweeps very far forward. This makes it very difficult structurally to take the required load and have the required stiffness for the new regulations."

Normally the load from the rear wing is passed down the endplates and through the lower beam. This cantilevered load makes the beam very difficult to mould to the ideal aerodynamic shape without adding undue weight. Toyota have gone back to the old method of a vertical strut to accept the upper wing's load in compression. This ends up being a lighter structure and the load path is straighter.

As the strut is quite short, it probably doesn't contribute much to the aerodynamics, which may prove useful as the regulations do not normally allow bodywork in this area. No doubt, Toyota has had this design agreed with the FIA.

As a result of the lighter loading on the lower beam, Toyota have twisted its profile making the centre higher and the outer ends moved forward and as low as the regulations allow. This makes the beam's interaction with the diffuser more effective; Gascoyne also adds that the regulation to move the upper wing forward reduced its ability to interact with the lower beam.

The floor is also an interim item, made in two pieces with the front splitter being detachable, which will be useful for trying different layouts and accessing the ballast mounted in the splitter. The splitter also features near full length fences mated to the horizontal fins in front of the sidepods.

At the rear, the lower outer diffuser channels are on display, and Gascoyne says the lower tunnels were easy to optimise – although it required severe initial steps and a large gurney to make it work. "By limiting the absolute height, it means you've got to make the first portion of the diffuser work as hard as you can,” the Briton says.

Where the floor has to be cut back around the wheels, a quarter rounded section was added ahead of the wheel and the half rounded section was added along the side of the wheel to prevent the higher pressure air above the floor finding its way underneath and upsetting the diffuser.

Chassis - Tyres

Unseen on the launch car was the underlying mechanical layout. This area had great attention during the design process. "There was nothing wrong with the fundamental layout - it was the detailed implementation that needed to be improved on, and I must say Gustav and his team did an excellent job on that,” Gascoyne comments.

The gearbox is still made in cast titanium with seven speeds, and the spring/dampers follow a similar layout. It is clear the rear torsion bars are pointing down at a greater angle and the dampers which set into the top of the gearbox are much tidier.

Gascoyne describes the new layout as "fundamentally the same, just improved in the details area. That means the overall package is one I'm much happier with - if you put them side by side you'd struggle to tell which is which. When you look at the things that we know from an engineering point of view, the characteristics we needed to have, this car has much better characteristics than last years did”.

Gascoyne goes on to tell Atlas F1 about traction control's effect on tyre wear: ”the trick is to have ultimate performance with traction control. The ultimate performance is actually allowing some degree of wheel-spin, but that causes tyre degradation. So now because you've got to keep that tyre for the whole race, you have to be more careful on how close you get to the limit of ultimate performance, trading that with degradation. Especially with reduced downforce, where you're sliding more, that's where you also get degradation.

"You can be quick with traction control, giving you ultimate performance, as you had last year. Or you can be sliding around and you can be quick, but your tyres are going to go off. If you've got to keep them on for another fifty laps that's going to be a key area."

This element of pace versus longevity excites Gascoyne, who says he loves the challenge of race strategy. "Managing the rear tyres is going to be a real skill,” he says. And, this in mind, he mentions that "Ralf [Schumacher] is one of the best guys on the grid at actually maintaining a good pace while managing the tyres."

Engine

As the team had a successful engine in 2004, they were already well into the development of the RXV05 engine, this project starting back in November 2003. As with the 2004 RXV04 engine, the development work to make the unit last the required mileage was complete by the previous season's end. Hence Toyota already have an engine able to last the two-race weekend totaling around 1,500km, some 700 more than the 2004 engine.

Repeating their claims from last year Marmorini's said that the engine was making the same peak power and revs as the late season version of the RXV04. The common belief that making an engine more reliable means making components heavier to cope, is in fact incorrect. Marmorini would not state an engine weight but said the new engine was two kilos lighter than in 2004.

Luca took the time to explain the engines design process. "As a target we took last year's engine, we started step by step to purely make the engine life longer, not changing parts in advance. At the end we have an engine very similar to last year, if Ralf tests our last engine it will look the same. He added Toyota are "not giving up performance, we are expecting to go to the first race with something higher than the best engine we assembled at the end of last year. "

To achieve this increase in mileage and maintaining performance, Marmorini commented quality control was critical, as small problems in components that would not occur at 800Kms would do so nearer 1,500km. Design wise the piston is not the limiting factor in reliability, but the bearings and their lubrication, finding a balance between thicker oil viscosities for reliability over thinner oil for performance.

"A Partner like Exxon gave us a big help for the longer reliability, in this case their contribution was going much beyond the normal percentage performance improvement for oil, and the oil supply was a huge part of the development"

Marmorini publicly explained that "the lower part of the engine has been optimised, but the concept is very similar to the older engine. The upper part of the engine has been completely redesigned." When speaking in detail about his work, he added the top end rework was to do with the inlets and variable length inlet trumpets. "This has been completely designed, we wanted to be even more extreme in the usage of short port and very long trumpet strokes."

In developing this engine through the year Marmorini warned the V8 project would not slow the V10 engine: "We will go on developing the V10 until the end of the season, at the end of the year to have the best V10 we can."

After three seasons in Formula One and four years since they began working on their F1 programme, Toyota have failed to live up to their potential. The 2004 car exhibited the same aerodynamic and mechanical failings of its predecessors, squandering a fantastic engine in the process.

A Year ago, Mike Gascoyne joined the team from Renault and started to rectify the chassis problems and take Toyota to the same level of process and performance as other F1 teams. This year's car shows some of the results of the team's reorganisation and is clearly a step forward for the team. As the first car launched to the new 2005 regulations, it shows some of the visual changes to the wings and displays some of the workarounds the teams will find in regaining the lost downforce.

A Year ago, Mike Gascoyne joined the team from Renault and started to rectify the chassis problems and take Toyota to the same level of process and performance as other F1 teams. This year's car shows some of the results of the team's reorganisation and is clearly a step forward for the team. As the first car launched to the new 2005 regulations, it shows some of the visual changes to the wings and displays some of the workarounds the teams will find in regaining the lost downforce.

With Gascoyne's experience and the corporate policy named "The Toyota Way” making changes to the team, an understanding of the team's procedural failings were identified. Almost ironically, Toyota's huge resources at the Factory in Cologne and across the group may have contributed to the team's problems. The huge weight of expectation for Toyota to succeed led the design team to use these resources to seek big gains with every redesign. Every new Toyota was a completely new design, throwing away a lot of the parts that worked in exchange for new parts designed from scratch.

With Gascoyne's experience and the corporate policy named "The Toyota Way” making changes to the team, an understanding of the team's procedural failings were identified. Almost ironically, Toyota's huge resources at the Factory in Cologne and across the group may have contributed to the team's problems. The huge weight of expectation for Toyota to succeed led the design team to use these resources to seek big gains with every redesign. Every new Toyota was a completely new design, throwing away a lot of the parts that worked in exchange for new parts designed from scratch.

"You can make it reliable mechanically, which of course you need to do," Gascoyne explains. "The downside, though, is that you need to freeze some parts early. That's why we are saying this car is going to be very different to Melbourne; we will put a new bodywork package on it. This means we have the most time for aerodynamic development.”

"You can make it reliable mechanically, which of course you need to do," Gascoyne explains. "The downside, though, is that you need to freeze some parts early. That's why we are saying this car is going to be very different to Melbourne; we will put a new bodywork package on it. This means we have the most time for aerodynamic development.”

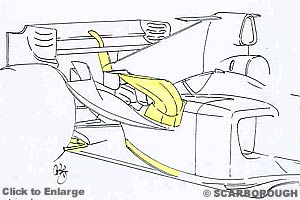

The sidepods are a departure for Toyota. Although keeping the square fronts and large chimney of the TF104B, the coke bottle area is now fashionably slim and the shape is almost straight-lined from the sidepod shoulders to the gearbox. This necessitates some bulges in their sides to accommodate the exhaust system. This slimming of the rear forces the small winglet behind the chimney to dog-leg slightly to reach out to the widest allowable position.

The sidepods are a departure for Toyota. Although keeping the square fronts and large chimney of the TF104B, the coke bottle area is now fashionably slim and the shape is almost straight-lined from the sidepod shoulders to the gearbox. This necessitates some bulges in their sides to accommodate the exhaust system. This slimming of the rear forces the small winglet behind the chimney to dog-leg slightly to reach out to the widest allowable position.

Also a novelty on the endplates is the stepped shape around the upper wing. As the lower portions are now nearer the rear tyres, they are spaced further away from the wheels' disturbance. Also, the way the step sweeps up behind the upper wing, suggests some method of flow management has been found to ease vortex production along with the three slits in the endplate.

Also a novelty on the endplates is the stepped shape around the upper wing. As the lower portions are now nearer the rear tyres, they are spaced further away from the wheels' disturbance. Also, the way the step sweeps up behind the upper wing, suggests some method of flow management has been found to ease vortex production along with the three slits in the endplate.

All this detail work had shed 8 kilogrammes off the chassis' weight, along with the initial improvements made to the TF104B. As a result, the team are happy that the stiffness, centre of gravity and weight are more competitive this year. Gascoyne even boasts that the car is now "state of the art in terms of packaging and Centre of Gravity location.”

All this detail work had shed 8 kilogrammes off the chassis' weight, along with the initial improvements made to the TF104B. As a result, the team are happy that the stiffness, centre of gravity and weight are more competitive this year. Gascoyne even boasts that the car is now "state of the art in terms of packaging and Centre of Gravity location.”

He also added that there were two factors preventing an even lighter engine. Installation stiffness, where the chassis would be compromised if the engine was lighter and less stiff, plus next year some materials are being banned within the engine, so they made this year's unit without them. Even common engineering materials like magnesium are banned, with the focus on steel and aluminium alloys. So impressively, Toyota have achieved their goals on power output, revs and weight already, and with an eye on the future.

He also added that there were two factors preventing an even lighter engine. Installation stiffness, where the chassis would be compromised if the engine was lighter and less stiff, plus next year some materials are being banned within the engine, so they made this year's unit without them. Even common engineering materials like magnesium are banned, with the focus on steel and aluminium alloys. So impressively, Toyota have achieved their goals on power output, revs and weight already, and with an eye on the future.

|

Contact the Author Contact the Editor |

Please Contact Us for permission to republish this or any other material from Atlas F1.

|

Volume 11, Issue 2

Articles

The Low-Key Approach

Technical Analysis: Toyota TF105

Open Wheel Racing: the Next Generation

Regular Columns

The F1 Trivia Quiz

Bookworm Critique

On the Road

Elsewhere in Racing

The Weekly Grapevine

> Homepage |