|

|

| The Best of the Best | |

| by Barry Kalb, Hong Kong | |

|

Atlas F1 is proud to present a series of features on the all-time greatest drivers of Formula One, written by veteran journalist Barry Kalb.

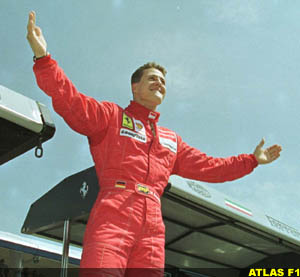

This week's feature: Michael Schumacher In almost any racing season, there are one or two drivers who possess that extra amount of drive, that extra bit of racing sense, and above all - that extra bit of innate physical ability, that put them a cut above the rest. Year in, year out, these men will give their all virtually any time they step into a racing car; they will dominate a season when they are in a good car, and produce wins nobody thought possible in a mediocre car; they will turn in performances that racing aficionados talk about for decades to come. This is their story.

Schumacher was only 25 years old when he won his first championship in 1994, one of the youngest champions ever and the first and only German to win the title. His highly contentious antics on the circuit that year may be put down to youthful indiscretion. But he will be a long time living down his actions in the final race of the 1997 season, when he deliberately and unmistakably drove into a rival -like Senna before him- to try to retain his championship lead. He was only three years older at that point, but he was now twice world champion, a veteran of six and a half seasons at the pinnacle of Formula One racing, accustomed to the attention and adulation of the fans, the news media, the world. One would think that kind of experience would give a person maturity beyond his years. Apparently it does not.

But Schumacher's skill is best seen on the track, not in the numbers. Like most of the great drivers before him, he is a master in the wet. At Spain in 1996, in a Ferrari that was markedly inferior to the Williamses, he was lapping six seconds faster than everyone else in a monstrous downpour, and he won the race. Stirling Moss later said of that event: "It was not a race. It was a demonstration of brilliance." In 1997, despite his car's inferiority, he came within a whisker of cobbling together a third world championship through a combination of intelligence, luck, and sublime ability: in the end, he lost to Jacques Villeneuve by only three points, piling up five wins and and three second places in the chase. He repeated the performance in 1998, coming second to Mika Hakkinen after fighting Hakkinen for the lead -again in a car that was demonstrably out-classed for most of the season - right to the wire.

He is a master a making his way through traffic, which is where many races are won or lost. He rarely makes a tactical mistake during a race: one can almost see him thinking as he drives. During the 1997 season, the on-board camera showed him during the furious first seconds of a race, calmly checking his left-hand mirror, calmly checking his right, while cars were exploding out of the gate all around him and he and the other leaders were making the dash for the first turn. The 1994 season, the deaths of Senna and Ratzenberger aside, was the most controversial in recent years up to that point, and Schumacher was the cause. First, he was black-flagged for passing during the parade lap at Silverstone, and when he failed to come in, he was suspended for two races. Then he won at Spa, only to be disqualified when a piece of wood that the FIA ordered placed on the undercarriage of all cars was worn down by a millimeter too much during the race. (It seems a silly way to lose, although there is good reason to believe the Benneton team was stretching the technological rules to give Schumacher a racing advantage - but then, Benneton just happened to be the team that got caught at it.)

Watching that incident over and over on videotape, it is difficult to say for sure that the crash wasn't an accident, although most people believe Schumacher ran into Hill on purpose in order to put him out of the race and secure the championship. If so, it was a repetition of Senna's deliberate collision with Prost in 1990, which put both of them out of the race and gave Senna his third title. And one can imagine what might have been going through Schumacher's head at the time: Senna did it; Senna got away with it; Senna is still idolized; I'll do it, too. In this case, Schumacher just about did get away with it. He won the championship in the Benneton in brilliant and non-controversial style the following year, and his skill was widely acknowledged. He moved to Ferrari in 1996, and through ability and force of will he helped bring the once-great team back into championship competition: the car was a pig in '96, and he still won three races, came third in the championship after Hill and Jacques Villeneuve in the Williamses. Schumacher was accorded the respect of a great driver, and he had earned it honestly. He fought Villeneuve mercilessly throughout 1997 in what was still an inferior car, remaining in contention for the championship all the way, and even those who didn't like him had to acknowledge his surpassing skill. It seemed he had truly put that incident at Adelaide behind him, and he was poised to win his third championship... and then he blew it.

Even though Schumacher had received his just desserts, there was a massive uproar over his tactics. He again protested that it had been an accident, that he was just taking the racing line and didn't see the Williams, but there was no room for doubt this time. A third of Villeneuve's car had already passed Schumacher before the German turned to the right. There is no way he could not have seen the Canadian; there was no way this super rational driver, so cool and controlled under pressure, so aware of everything going on around him, could have "accidentally" run into the Williams. It was clear he was again trying to win the championship by running a rival off the track, and a lot of people, including Villeneuve himself, said so publicly. In the end, Schumacher agreed that it had been "a mistake." He escaped with a minor slap on the wrist from the FIA, and he regained a large measure of international respect in 1998, when he harried Hakkinen all season, scored some brilliant wins, and again lost the championship only in the final race.

Modern-day sports heroes do what they want. They are international celebrities, often better known (and better liked) than national political leaders. They are paid unimaginable sums of money, they are fawned over, they are lionized in the press. They are spoiled. If they're caught in some questionable act - abusing drugs, assaulting women, acting in a manner that brings dishonor to their sport - they mumble half an apology, say they want to "put the incident behind them," and hope it's all forgotten in a few weeks or months. It happens in soccer, American football, boxing, baseball, basketball. And, since the time of Ayrton Senna, it happens in Formula One. This time, it will not be completely forgotten. When the baseball player Roger Maris broke Babe Ruth's record of 60 home runs in a season in 1961 - Maris's was the record finally broken last year by Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa - a footnote was put into the record books, pointing out that the playing season had been lengthened that in 1961, so that Maris had more games than Ruth in which to reach the record. It is likely, because of 1994 and '97, that Schumacher, too, will always have an "asterisk" hanging over his head: one of the all-time greats, an incontrovertibly brilliant driver - but a flawed individual.

|

| Barry Kalb | © 1999 Atlas Formula One Journal. |

| Send comments to: bkalb@asiaonline.net | Terms & Conditions |

Barry Kalb is a veteran journalist of 20 years' experience (the Washington Star, CBS News, Time Magazine) and a motor racing fan - especially Formula One - for almost 40 years. He currently resides in Hong Kong. | |

Michael Schumacher is a racer in the Senna mold: superb driver, brilliant race tactician, extremely exciting to watch on the track, able to produce wins even when the odds and his car are against him. During a time when Formula One races often turn into boring processions, when almost nobody passes anybody else except in the pits, Schumacher, like Senna before him, is always pushing, trying, bulling his way past other drivers. Like Senna, he is also the arrogant, spoiled, modern-day sports star, who seems to believe his stardom allows him trespasses that are denied to normal mortals.

Michael Schumacher is a racer in the Senna mold: superb driver, brilliant race tactician, extremely exciting to watch on the track, able to produce wins even when the odds and his car are against him. During a time when Formula One races often turn into boring processions, when almost nobody passes anybody else except in the pits, Schumacher, like Senna before him, is always pushing, trying, bulling his way past other drivers. Like Senna, he is also the arrogant, spoiled, modern-day sports star, who seems to believe his stardom allows him trespasses that are denied to normal mortals.

During seven and a half seasons of racing, in 118 starts, the young German has produced one of the very finest records in Formula One. As of the end of the 1998 season he had 33 championship wins, putting him in third place overall after Prost and Senna, and he seems almost certain at least to surpass Senna before his career is over. He is third in podium finishes (65) and points scored (526), second in fastest laps (34), and he could easily end his career in first or second place in all those categories as well. Statistically, he is in the top three or four in every major category except poles per start (he ranks 10th there), consistently ahead of Prost and Senna.

During seven and a half seasons of racing, in 118 starts, the young German has produced one of the very finest records in Formula One. As of the end of the 1998 season he had 33 championship wins, putting him in third place overall after Prost and Senna, and he seems almost certain at least to surpass Senna before his career is over. He is third in podium finishes (65) and points scored (526), second in fastest laps (34), and he could easily end his career in first or second place in all those categories as well. Statistically, he is in the top three or four in every major category except poles per start (he ranks 10th there), consistently ahead of Prost and Senna.

It is almost impossible, unless one is really close to the track, to get a feel for what modern-day Grand Prix cars are doing in a corner. They no longer drift, they only occasionally twitch, one has little idea what the driver is doing unless the on-board camera happens to be on the television screen. Long-lens television angles compound the situation by slowing the cars down visually. The upshot: it is difficult for today's spectator to detect much difference between one car and another, unless drivers of vastly different ability are going through a curve at the same time. But watch Schumacher lapping, even on television, and you can see that he's going through the corners faster than anyone else. His car just seems to skate across the tarmac. He makes passes that most people thought impossible - including the poor driver he has just passed.

It is almost impossible, unless one is really close to the track, to get a feel for what modern-day Grand Prix cars are doing in a corner. They no longer drift, they only occasionally twitch, one has little idea what the driver is doing unless the on-board camera happens to be on the television screen. Long-lens television angles compound the situation by slowing the cars down visually. The upshot: it is difficult for today's spectator to detect much difference between one car and another, unless drivers of vastly different ability are going through a curve at the same time. But watch Schumacher lapping, even on television, and you can see that he's going through the corners faster than anyone else. His car just seems to skate across the tarmac. He makes passes that most people thought impossible - including the poor driver he has just passed.

But the greatest controversy of all that year came in the final race, at Adelaide. Schumacher was leading the championship with 92 points, Damon Hill was right behind at 91; if either won in Australia, he would be champion. Schumacher took the lead at the start, but ran wide on an early lap and damaged the right side of his car too badly to continue. Hill, who was right behind and now had a clear shot at the championship, went to pass Schumacher's ailing car in a tight right-hand curve; Schumacher cut right across his path and rammed into him, damaging Hill's left front suspension just enough that he had to retire a lap later.

But the greatest controversy of all that year came in the final race, at Adelaide. Schumacher was leading the championship with 92 points, Damon Hill was right behind at 91; if either won in Australia, he would be champion. Schumacher took the lead at the start, but ran wide on an early lap and damaged the right side of his car too badly to continue. Hill, who was right behind and now had a clear shot at the championship, went to pass Schumacher's ailing car in a tight right-hand curve; Schumacher cut right across his path and rammed into him, damaging Hill's left front suspension just enough that he had to retire a lap later.

Again, it was down to the last race of the season. Again, the difference going into the final race was one point: Schumacher 78, Villeneuve 77. If either Schumacher or Villeneuve won the European Grand Prix at Jerez, he would be champion. Schumacher led from the start, but then his tires started to go. Villeneuve caught him on the straight, and was about to pass on the inside entering a right-hander, when Schumacher turned into him. This time, the tactic didn't work: Schumacher put himself out of the race, while the damage to Villeneuve's car was minor, and he went on to finish third and take the championship.

Again, it was down to the last race of the season. Again, the difference going into the final race was one point: Schumacher 78, Villeneuve 77. If either Schumacher or Villeneuve won the European Grand Prix at Jerez, he would be champion. Schumacher led from the start, but then his tires started to go. Villeneuve caught him on the straight, and was about to pass on the inside entering a right-hander, when Schumacher turned into him. This time, the tactic didn't work: Schumacher put himself out of the race, while the damage to Villeneuve's car was minor, and he went on to finish third and take the championship.

Why would so intelligent a man as Schumacher risk his reputation with so blatant an act - let alone risking his and Villeneuve's safety with a deliberate high-speed crash?

Why would so intelligent a man as Schumacher risk his reputation with so blatant an act - let alone risking his and Villeneuve's safety with a deliberate high-speed crash?