|

Formula One drivers are far from being playboys who spend their times in bar, bulging down junk food and alcoholic drinks. Far from it. And their diet and fitness, while being the strictest of its kind, can sometimes be a matter of life and death.

Formula One aficionados have always known that fuel plays a major factor in the success of a racing team. This is obvious when one watches a Grand Prix race from beginning to end.

There's another kind of fuel that is as important as race mix to success on the track - the food that a driver ingests as part of his regular diet. The food factor has a crucial role to play in Formula One, and diet, as much as overall physical fitness allied to natural skill, is an essential ingredient in the strategy for Grand Prix success.

Food, leading to strength and weight control, is important to the F1 driver, whose job makes specific demands on him. Ideal diet and optimum performance weight, of course, depend on the particular demands of the many and varied sporting arenas. Food, leading to strength and weight control, is important to the F1 driver, whose job makes specific demands on him. Ideal diet and optimum performance weight, of course, depend on the particular demands of the many and varied sporting arenas.

A lesson in stark contrasts would be the comparison of an F1 driver with a Sumo wrestler. And yet diet, in utterly different ways, is vital and central to performance at the very highest level in both sports.

The average Grand Prix driver weighs around 65 kgs, with minor fluctuations, and carries virtually no fat on a lithe, but strong and muscular body with fine definition. Conversely, the Japanese wrestler can tip the scales at 260 kgs and more, and a considerable proportion of his massive frame, designed specifically for the job of manhandling the opposition, comprises solid fat.

Dietary extremes

The body condition of both sportsmen, fashioned by diet and exercise, is absolutely essential to their prowess. The physical demands of their activity shapes their needs - but even so, a carefully constructed dietary programme is a basic requirement before they can bring their skills and strength into play and maximise their God-given talents.

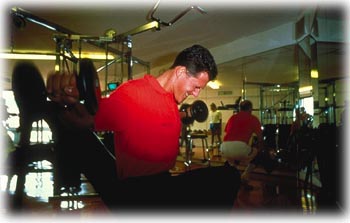

Drivers are as finely tuned as their engines - and nurtured just as thoroughly and as carefully for ultra performance under great stress. Not only do they train almost obsessively in the gymnasium to strengthen their bodies, particularly their necks and forearms, but their diets are meticulously planned and supervised by nutritionists guidance in an effort to provide the optimum fuel that will match their efforts in weight training and aerobic exercise. The analogy on the racetrack is the properly sequenced pit stop for fuel, and the testing runs that help with the set-up of the car.

Compare the Sumo wrestler's needs. He dedicates his life to getting bigger and stronger every day for the collisions that can spell the difference between magnificent success and miserable failure in an arena where bulk is considered beautiful. That means a diet in the neighborhood of an astronomical 18,500-19,000 calories a day, spread over many meals rich in protein and carbohydrates. Calorie levels are boosted by a menu that would send a dietician screaming into the night - fried food, sweet biscuits and sugary cakes, and litres of alcohol, mainly beer, but plenty of sake too.

Compare that with a racing driver's essential and carefully monitored diet: he, in contrast, needs only 2,000-4,000 calories a day, and gets it from meals that are created specifically to keep him in the sort of trim that not only pleases his tailor and significant other, but his team chief as well. These meals are high in complex carbohydrates, but as near zero as possible in fat content. The slightest increase in fat affects his efficiency and a heavy meal, loaded with fats, boosts the lipids in the bloodstream. That's not good when his overworked heart might need all the help it can get as it surges from around 60 beats a minute to 240 beats in a race. Compare that with a racing driver's essential and carefully monitored diet: he, in contrast, needs only 2,000-4,000 calories a day, and gets it from meals that are created specifically to keep him in the sort of trim that not only pleases his tailor and significant other, but his team chief as well. These meals are high in complex carbohydrates, but as near zero as possible in fat content. The slightest increase in fat affects his efficiency and a heavy meal, loaded with fats, boosts the lipids in the bloodstream. That's not good when his overworked heart might need all the help it can get as it surges from around 60 beats a minute to 240 beats in a race.

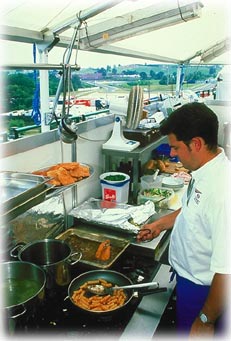

Team nutritionists are as vital to drivers as engineers are to cars and they attend all the races, sometimes even cooking special meals, but always making sure they keep an eye on the waistlines of their charges. A race driver's dinner, after a breakfast of muesli or porridge with sliced banana and grated apple, and a mid-morning fruit snack and litres of mineral water, might be a bowl of vegetable soup, a piece of whole-wheat bread without butter, a plate of pasta with low fat sauce, steamed broccoli, yogurt, dried fruit and nuts - and fruit juice or mineral water.

Red meat is banned. So are junk food and alcohol, sugar and any food that contains fat. An egg is considered a once-a-week treat.

Today's racing drivers no longer conform to the popular stereotype of the high-living, risk-taking daredevils of bygone eras. Instead, they are an abstemious breed. Ask any of them to nominate their favourite foods or drink, and the replies will not encourage a master chef.

Gone, all too clearly, are the days of the Golden Era in the Roaring Twenties and Dirty Thirties when men such as Italian opera singer-cum-race driver Giuseppe Campari fortified himself with red wine before battle; or team owner Rob Walker who was refreshed during the Le Mans 24 Hours by the odd glass of champagne. More recently, most of the French drivers like Patrick Depailler or Jean-Pierre Jarier would normally down a glass of red wine with lunch before the race.

These days, alcohol is usually on the no-go list for driver on race weekend, although many will enjoy a beer or a glass of wine with dinner if they don't have to drive for a couple of days.

Merge diet with fitness

At a race and during testing, most teams have their own dieticians and fitness gurus whose specific job is to merge diet with fitness in healthy regimens for their drivers. They also make sure that the food is properly prepared. At Ferrari, Irvine's sister Sonia makes sure that he eats what is good for him. "Eddie knows what he should eat. After he gets out of the car, he'll enjoy his pasta. I have to keep telling him to eat more vegetables," she says.

But do top drivers ever rebel against the stringent fitness regimes forced upon them? Or does the need to maintain a jockey's fitness and stature of overriding importance even away from races?

Fitness guru Josef Leberer, formerly at McLaren, recalls Nigel Mansell's struggle to discipline himself - and re-educate his palate: "Nigel knew what was good for him, but he liked to eat a lot. He would eat twice what I gave him and he liked pudding. At the beginning I had to cut him back a lot, and be quite strict and say, 'Look, this much is not necessary.' He would make a joke of it, and leave the food I said he couldn't have on the side of his plate. In one test he lost about four kilos. He and wife Rosanne said they wanted to continue the diet. It worked, though when the car wasn't going well, he would get frustrated and start eating again." Fitness guru Josef Leberer, formerly at McLaren, recalls Nigel Mansell's struggle to discipline himself - and re-educate his palate: "Nigel knew what was good for him, but he liked to eat a lot. He would eat twice what I gave him and he liked pudding. At the beginning I had to cut him back a lot, and be quite strict and say, 'Look, this much is not necessary.' He would make a joke of it, and leave the food I said he couldn't have on the side of his plate. In one test he lost about four kilos. He and wife Rosanne said they wanted to continue the diet. It worked, though when the car wasn't going well, he would get frustrated and start eating again."

Leberer had much more success with the current generation at McLaren. "Mika Hakkinen and David Coulthard are already quite healthy," he says, "so you can give them high quality food and the amount doesn't matter. They are no problem at all. I give them muesli, fruits, cereals, tea for breakfast, and pasta, soups, vegetables and salads for lunch. Sometimes it's fruit or herbal tea, but why should they change everything? David likes his English tea so we make it weak. And he drinks lots of water, which is fantastic for cleansing the system. He likes Highland Spring mineral water, so we checked what is in it, and it's perfect."

Fit To Race

"There's only one way to get truly fit to drive an F1 car, and that's to drive one." - Those words from 1978 World Champion and American racing legend Mario Andretti still ring true today. There is no substitute to being behind the wheel to get race fit. But, as today's modern physical fitness adepts will attest, there must be a platform of basic physical fitness on which to build.

Austrian fitness guru Willi Dungl pioneered health and fitness programs in Formula One, and helped rescue fellow countryman Niki Lauda's career after his fiery crash at Nurburgring in 1976; Tennis stars Thomas Muster and Steffi Graf are other products of the Dungl fitness programme. Today, Dungl spends most of his time at his world-famous clinic and Leberer has taken over the missionary work with the speed demons of Formula One. Leberer struck out on his own in 1995, after having enjoyed a long, fruitful relationship with the late Brazilian superstar, Ayrton Senna, a man he considered the fittest driver he had ever worked with.

"After Senna started training, the other drivers soon came to realise that they couldn't be competitive without being physically fit," Leberer recalls. "Today, there is practically no difference between the drivers in this area, especially the younger ones. Mika Hakkinen says the same as Mario, and testing is not the same as racing 70 laps, either. That's a different pressure. You have to build up the muscles. There are many exercises, and even cross-country skiing is good because you isolate certain muscles." "After Senna started training, the other drivers soon came to realise that they couldn't be competitive without being physically fit," Leberer recalls. "Today, there is practically no difference between the drivers in this area, especially the younger ones. Mika Hakkinen says the same as Mario, and testing is not the same as racing 70 laps, either. That's a different pressure. You have to build up the muscles. There are many exercises, and even cross-country skiing is good because you isolate certain muscles."

Normal, recognised physical activity like cross-country is one thing, but can the stresses and strains of an actual race be duplicated in a programme?

Quicker recoveries from crashes

"We have different equipment that helps simulate sitting in the cockpit, and we might place certain weights on a helmet to force the right impulse on muscles and nerves that might recall the G-forces one would feel in a racing car. It's the same with Mika," adds Leberer, referring to a horrific crash in Australia in 1995 that left Hakkinen with a broken skull and all manner of broken bones.

"If you or I had the same accident, forget it, our necks would not have been strong enough. The condition of one's cardiovascular system is also important, and so is one's musculature. The power and energy have to be there and you must train all the time to maintain top fitness levels."

Hakkinen's extraordinary physical fitness not only saved his life, it allowed him to return to F1 racing sooner than might have been expected. At the time of his accident, doctors ruled out resumption of his racing career; 1,000 days later he won his WC.

At Ferrari, Eddie Irvine's sister, Sonia, does all the training supervision. A qualified physiotherapist, she gave up her own practice to concentrate on her brother's physical well-being. Sufficiently fit herself, thanks to a daily program, she is able to keep up with Eddie's daily routine. "I normally drive Eddie to the racetracks, and depending on what time we're meeting, I'll go down to the gym with him and do an hour. I really enjoy it," she says. At Ferrari, Eddie Irvine's sister, Sonia, does all the training supervision. A qualified physiotherapist, she gave up her own practice to concentrate on her brother's physical well-being. Sufficiently fit herself, thanks to a daily program, she is able to keep up with Eddie's daily routine. "I normally drive Eddie to the racetracks, and depending on what time we're meeting, I'll go down to the gym with him and do an hour. I really enjoy it," she says.

Jacques Villeneuve spent a year with another Dungl disciple, Irwin Gollner. Damon Hill has his own special regime: "I favour cross-country skiing at the right altitude, 1,700 metres," he says. "The higher you are, the less oxygen there is so you have to work harder. That gets you your oxygen flow going and stimulates the red corpuscles, so in the end you are able to perform better because your cardiovascular system is peaking. Cross-country skiing exercises a whole range of muscle, and that's important. Also, it's good on muscles and joints because it's not as violent as running or mountain biking."

One has to build up a good musculature without damaging ligaments and joints, Hill believes. "Swimming is also excellent, if you pick the right strokes. You need a variety of breaststroke and crawl, and backstroke is the best because it trains the opposite muscle group than you use normally as a driver when you are sitting in the cockpit with your arms out in front of you."

Frenchmen Pierre Balleydier and Patrick Champagne take care of Team Prost fitness requirements. Champagne became Olivier Panis' personal physio after the terrible crash at Montreal in 1997 that left the driver with two broken legs. Balleydier worked with Alain Prost when he was a driver for Team McLaren in the 1980's, and has long based his programme on cycling.

"The main thing for a driver is flexibility, and as a trainer you have to find the right way for him," Balleydier says. "He has to believe in you completely, to trust you, and then you can be successful. Whatever the situation, you have to support the driver" "The main thing for a driver is flexibility, and as a trainer you have to find the right way for him," Balleydier says. "He has to believe in you completely, to trust you, and then you can be successful. Whatever the situation, you have to support the driver"

Dominique Sappia looked after drivers Pedro Diniz and Mika Salo for Team Arrows, and worked with Hill in 1997. "These drivers are so fit that I have a hard time preparing their programmes! I always made sure during the season that their hotel will have a gym, and oversee their winter training regimen so they will be 'super-fit' going into the new season," says Sappia. He is another strong believer in the benefits of cross-country skiing. "I allowed the snowmobiles, and Mike Salo turned this into an endurance race, from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. every day," Sappia adds.

"One thing is certain; today's racing drivers are superbly conditioned athletes with nothing in common with the gentlemen racers of the 1950s and '60s," He sums it up.

|