|

PROLOGUE

PROLOGUE

The man speaking is Michael Schumacher. The time and place is just minutes after his victory in the 1998 Canadian Grand Prix. "That was purely dangerous driving. If someone wants to kill you, he should do it in a different way. We are doing 200 mph down there, and for someone to then move off line a total of three times is completely unacceptable." That "someone" was of course Damon Hill and in the context of modern Formula One, the incident that had got Schumacher's attention can only be rated as a

mere ripple in the never still waters of Formula One.

Within hours Damon Hill had responded. "He always seems to be angry with me about something, but I didn't do anything wrong. We were racing and I made it hard for him to pass." As always the media were the willing conduit along which the messages were passed. Schumacher and Hill, attack and defence, right and wrong.

In the context of the season it was a non-event. But fleetingly it brought back memories of that bitter and tragic year of 1994 when these two drivers fought out a seemingly never ending battle for motor racing's ultimate prize - the drivers' World Championship. Now the rivalries had moved on, each in his own way had discovered new enemies, but somehow the clashes were less personal and the words more ritualistic. A battle to be fought for the battle's sake, the need not there to destroy the foe.

BEFORE

Michael Schumacher came to the '94 season in good shape. Benetton had produced a neat and tidy car powered by an all new Ford-Cosworth Zetec-R engine. After making his debut in the 1991 Belgian Grand Prix for Jordan, he had been smartly poached by the canny Tom Walkinshaw - then the technical director at Benetton - by the next race. He possessed blistering speed and the confidence to fully exploit it.  Nurtured through the lower rungs by Mercedes-Benz, his progress to Formula One was assured. Not for Michael Schumacher the struggle to pay the bills or to look for sponsors. If Schumacher learnt fast inside the car he was also not slow to learn the intrigues and politics outside of it either. Nurtured through the lower rungs by Mercedes-Benz, his progress to Formula One was assured. Not for Michael Schumacher the struggle to pay the bills or to look for sponsors. If Schumacher learnt fast inside the car he was also not slow to learn the intrigues and politics outside of it either.

The Formula One paddock demands that you show no weaknesses. He didn't. If he made mistakes he learned from them fast. During the 1992 season he was more than occasionally rattled by the race speed of the lowly rated Martin Brundle. From that year onwards he has always insured by way of the terms of his contract that he would ever be so troubled by a teammate again.

In many ways, the Benetton team of '92/'93 was ideal for his formative years, good enough for him to impress, but not rated as automatic winners. For Schumacher it gave the opportunity to show what he could do, but without the pressure.

For Damon Hill the entry into the top flight was via a very different door. The call from Frank Williams came in December of 1992. For two years Hill had been the Williams team's test driver. A series of drives in under-funded teams saw him arrive into Formula One with the Brabham team, then in its death throes. Williams were then at the height of their power as Formula One winners and three time champion Alain Prost would lead them for '93, replacing the departing Nigel Mansell. Just how do you "negotiate" with Frank Williams from Hill's position of acute weakness? In truth he took what was offered, around US$500,000 per season, and became a full time Grand Prix driver in the best team in the business. Many drivers in the pitlane would have taken the drive for less!

Here, though, the seeds of so much of what was to follow were sown. Hill's new contract was not a fresh one, just an extension of his old test-driver contract and its terms did not even guarantee him a race drive. This was a reflection as to just how Frank Williams regarded him and even when he had become statistically one of Williams' most successful drivers nothing much changed. Later in '94, when he was challenging for the title, the returning Nigel Mansell would command almost double for one race what Hill was being paid for the whole season.

Damon Hill was in many ways an ordinary man pitched into the extraordinary world of the most glamorous sport on earth. A man without guile, his natural inclination was to take people at their word. He had been brought up to speak up for what was right, and more importantly - to do what was right. Admirable qualities for the road through life, something of a handicap in the shark-infested waters of Formula One. Damon Hill was in many ways an ordinary man pitched into the extraordinary world of the most glamorous sport on earth. A man without guile, his natural inclination was to take people at their word. He had been brought up to speak up for what was right, and more importantly - to do what was right. Admirable qualities for the road through life, something of a handicap in the shark-infested waters of Formula One.

For a first season his results were impressive. Three wins secured and as many again slipped through his fingers through no fault of his own. His one year deal was renewed and Ayrton Senna replaced Alain Prost for the '94 season. As the teams headed off to Brazil the cast of characters for the tumultuous year was complete.

COMBAT

The death of Ayrton Senna at Imola changed everything. Schumacher won the opening two races and showed that he and the Benetton were more than a match for the Williams, even with Senna driving it. The new rules introduced for that year did away with much of the technology that Williams had mastered and that had provided them with their edge. If Senna had struggled, just what hope did Hill have? Precious little in the opinion of many, including the Williams' engine supplier, Renault.

By mid-season it seemed that they were right. Going into the eighth round of the championship in Britain, Schumacher had scored six victories to one and led in the points standings by 66-29. It was not so much a contest but more of a victory parade.

That British Grand Prix changed everything. Damon Hill won from pole a race that his double world champion father had never won. The boost to his confidence was immeasurable, coming as it did just seven days after he had out-qualified and out-raced the returning Nigel Mansell at the French Grand Prix.

On Mansell's return, at the insistence of Renault, he confirmed the comments that Hill had been making all season on the handling problems inherent in the Williams FW16. Later, designer Adrian Newey would confirm the reality of what the drivers had been saying. "To be honest we made a bloody awful cock up. The rear-end grip problem was purely a set-up problem. We were learning about springs and dampers all over again after concentrating on active suspension for two years." On Mansell's return, at the insistence of Renault, he confirmed the comments that Hill had been making all season on the handling problems inherent in the Williams FW16. Later, designer Adrian Newey would confirm the reality of what the drivers had been saying. "To be honest we made a bloody awful cock up. The rear-end grip problem was purely a set-up problem. We were learning about springs and dampers all over again after concentrating on active suspension for two years."

For Michael Schumacher and Benetton the British Grand Prix was the start of a roller coaster ride of seemingly constant confrontation with the FIA. For reasons that have never been fully explained, Schumacher chose to overtake the Williams of Hill during the pre-start parade lap, not just once but twice, the first start having been aborted when David Coulthard stalled. When he ignored the black flag shown to him on two successive laps, a chain of incidents started which were to almost cost him his championship.

Second on the road at Silverstone he would subsequently be excluded from the results and banned for a further two races for ignoring the black flag. The Benetton team were also fined US$500,000 for failing to obey the instructions of the race officials.

Schumacher raced on under appeal, winning again in Hungary, but was controversially excluded from the Belgian race, where he finished first on the road, due to a technical infringement concerning excessive wear of the newly installed "plank" on the underside of his Benetton. Hill, who had finished second on the road, inherited a lucky win and then went on to rub salt into the wounds by winning the next two races from which Schumacher had been excluded.

Schumacher made his return to racing at the European Grand Prix, to be held at Jerez, but his once overwhelming points lead had now been trimmed to just on point. Just prior to the Spanish race Schumacher launched a vitriolic attack against his only championship rival stating that he didn't consider Hill a world class driver.

Speaking directly to the British press the timing and nature of his comments were clearly designed to destabilise Hill at what was to be a pressure race for both men. Hill's dry rejoinder, that "my dad beat Jim Clark, and it's examples like that which remind you that everyone puts their trousers on one leg at a time" made a subtle point. Clearly Schumacher saw himself as the sport's only superstar and he was more than a little irked that such a lowly ranked rival could still be in with a chance of taking a title he now considered was already his by right. Speaking directly to the British press the timing and nature of his comments were clearly designed to destabilise Hill at what was to be a pressure race for both men. Hill's dry rejoinder, that "my dad beat Jim Clark, and it's examples like that which remind you that everyone puts their trousers on one leg at a time" made a subtle point. Clearly Schumacher saw himself as the sport's only superstar and he was more than a little irked that such a lowly ranked rival could still be in with a chance of taking a title he now considered was already his by right.

Both knew however that the results on the track would decide who had the last laugh. In many ways, the race in Jerez in '94 would sum up so much of what was to follow. Hill took pole and led the race easily. With the Williams on a two stop strategy and the chasing Benetton on a three stop routine, Hill was in a strong position. When the Williams refuelling rig suffered a glitch the race was lost and once again the British hero had come off second best.

For the tabloids especially, detailed analysis is not their strong point, and the Williams team are not noted for the speed at

setting the record straight. Schumacher winning again was the only story in town and now he was only a small step away from clinching the title.

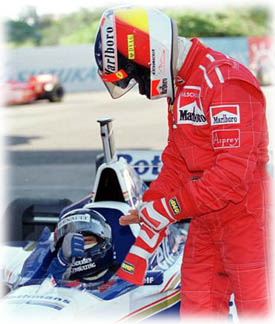

When Schumacher was beaten by Hill in the Japanese race he looked totally shell-shocked. Standing stony faced on the podium he was clearly living out a nightmare. To finish second to a driver that he had heaped so much contempt on challenged his self belief to the core. It came as little surprise then, that just minutes after winning the title in Australia in controversial circumstances, he would apologise for his earlier criticism of Hill's driving abilities. For once no rejoinder from Hill was required; he had done all his talking on the track.

EPILOGUE

In the media driven age in which major sports stars now compete, the Hill-Schumacher rivalry was a boon to everyone. Millions all around the world tuned in to watch another episode in the seemingly never ending saga. In a strange way it seems that perhaps they needed each other. In the days leading up to his death even Ayrton Senna was making conciliatory gestures to his once despised rival Alain Prost. Sometimes great sportsmen need a rival to reflect their talent against. What would Mohammed Ali have been without Joe Frazier, Sebastian Coe without Steve Ovett, or even Manchester United without Liverpool. In the media driven age in which major sports stars now compete, the Hill-Schumacher rivalry was a boon to everyone. Millions all around the world tuned in to watch another episode in the seemingly never ending saga. In a strange way it seems that perhaps they needed each other. In the days leading up to his death even Ayrton Senna was making conciliatory gestures to his once despised rival Alain Prost. Sometimes great sportsmen need a rival to reflect their talent against. What would Mohammed Ali have been without Joe Frazier, Sebastian Coe without Steve Ovett, or even Manchester United without Liverpool.

1995 was a year that saw Hill and Schumacher battle yet again for the title, only for Schumacher to clinch it with more ease and less controversy than the previous year. For Damon Hill, however, final vindication came during 1996 when he clinched his world championship with a dominating drive in the Japanese Grand Prix. Schumacher, in the first year of his rebuilding programme with Ferrari, was never a serious challenger. But as has always the case with Hill it was a bitter sweet moment, as his winning drive was also his last for the Williams team for which he had given so much. Team owner Frank Williams decided against renewing his contract.

Sporting heroes come and go, all too soon their achievements blurred as the memories fade. What remains are perhaps just the highs or lows of a long career. A general ranking of achievements. Subtly though, their character and the manner in which they conducted themselves throughout their very public careers will remain. An indelible impression made that can never be erased.

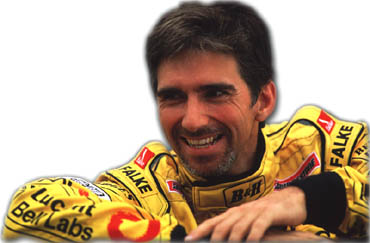

When Damon Hill steps from his Jordan for the last time in 1999, he will be remembered for more than just his racing record. For a generation of racing fans it will be in some ways an end of an era and proof that sometimes good guys can finish first. Not all will earn such favourable reviews.

|