|

|

| The Best of the Best | |

| by Barry Kalb, Hong Kong | |

|

Atlas F1 is proud to present a series of features on the all-time greatest drivers of Formula One, written by veteran journalist Barry Kalb.

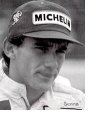

This week's feature: Ayrton Senna In almost any racing season, there are one or two drivers who possess that extra amount of drive, that extra bit of racing sense, and above all - that extra bit of innate physical ability, that put them a cut above the rest. Year in, year out, these men will give their all virtually any time they step into a racing car; they will dominate a season when they are in a good car, and produce wins nobody thought possible in a mediocre car; they will turn in performances that racing aficionados talk about for decades to come. This is their story.

Senna's mastery in a Formula One car is a given. He was champion three times, in 1988, 1990 and 1991. He won more championship races, 41, than any driver except Alain Prost (51), and was second only to Prost in total points scored and podium finishes. He was on the pole a record 65 times (13 times out of 16 races during both the 1988 and 1989 seasons), almost doubling the 33 poles won by Prost and Clark (although Clark had a better poles-per-start ratio). Like other great drivers, he added brains to driving ability, always looking for - and usually finding - that extra advantage, that extra tenth of a second. He turned in some of the most spectacular drives ever seen, most notably his electrifying win in the wet at Donington in 1993, over the demonstrably superior Williamses of Prost and Damon Hill. He managed four wins that year in an out-classed McLaren, and three the previous year when Nigel Mansell was running away with the championship in that same dominant Williams. After Senna's fatal crash at Imola in 1994, the three-time champion Niki Lauda said: "Senna was the greatest driver ever."

He lived for Formula One, he excelled at it, and he changed it, although not for the better. He introduced tactics that were foreign to the sport, and for good reason: they were terribly dangerous - driving people off the track, for example, or purposely crashing into Prost at the start of the Japanese Grand Prix in 1990 in order to secure the championship for himself. There had been plenty of Grand Prix drivers before Senna who were dangers to themselves, and many of them paid for their recklessness with their lives, but Senna was arguably the first driver to be purposely dangerous to others. It has been suggested that Senna adopted this potentially lethal style of driving partly because he could - because modern technology had seemingly made Grand Prix cars so strong, so safe, that the danger of death had all but been eliminated from the sport. "There can be no denying that (Senna) did more than anyone to bring crude dodgem tactics to Formula One, his initiative rendered relatively risk-free by the fat rubber tyres and immensely strong survival cells of the current cars," the British sports journalist Richard Williams wrote in his post-mortem tribute, "The Death of Ayrton Senna". To be sure, drivers have lived in recent years through crashes that surely would have been fatal in the past: Riccardo Patrese, his Williams somersaulting through the air at Estoril in 1992 after running up the back of Gerhard Berger's car; Martin Donnelly lying on the track, alive, amid the total wreckage of his Lotus in Spain in 1990; Berger escaping with minor burns after hitting the wall in 1989 and being engulfed in a fireball for over 20 seconds, at the same spot where Senna later died. In fact, incredible as it may seem to anyone familiar with the history of the sport, until the weekend Senna and the Austrian Roland Ratzenberger were killed at Imola, no driver had died in a Grand Prix race for twelve years, since Ricardo Paletti during the Canadian Grand Prix in 1982. (Elio de Angelis was killed during testing in 1986 in France.)

Today's Grand Prix drivers generally drive only in Formula One world championship events, unlike their counterparts in the 1950s, '60s and '70s, who also drove in non-championship Formula One races, Formula Two races, sports car races, hill climbs, endurance races, sometimes even rallies. It was often in those other type of races that Grand Prix drivers met their deaths: Clark died in a Formula Two race, for example, Bonnier at Le Mans, Ludovico Scarfiotti in a hill climb. But most died in Formula One cars, either testing, like Ascari, or racing. Motor racing is dangerous, often deadly, and Senna seems to have forgotten or ignored that fact.

Unfortunately, we will never know. He died the day after Ratzenberger as the actual race was just getting started, hitting a concrete wall outside the Tamburello curve at 131 mph. The accident was eerily reminiscent of Moss's final crash at Goodwood 32 years earlier: in both cases, these seemingly infallible drivers entered a fast curve and simply went straight on instead of making the turn; it was not apparent to those watching that the drivers even tried to turn their cars, although according to journalist Richard Williams, computer telemetry - which did not exist in Moss's day - indicated that Senna was indeed turning the wheel in the direction of the curve until moments before the fatal impact. For all his daredevil habits, there are strong indications that Senna fell victim to some mechanical failure, and not to some momentary lapse in judgement or concentration. * Among drivers who participated seriously in Formula One since the modern championship began in 1950, the list of those killed in racing cars looks something like this: Luigi Fagioli was killed in 1952. Felice Bonetto in 1953. Onofre Marimon in 1954. Alberto Ascari in 1955. Louis Rosier in 1956. Eugenio Castellotti and Alfonso de Portago in 1957. Peter Collins, Luigi Musso and Stewart Lewis-Evans in 1958. Jean Behra in 1959. Harry Schell in 1960. Wolfgang von Trips in 1961. Ricardo Rodriguez in 1962. Carel De Beaufort in 1964. Lorenzo Bandini in 1967. Jimmy Clark and Mike Spence in 1968. Lucien Bianchi and Gerhard Mitter in 1969. Jochen Rindt, Bruce McLaren and Piers Courage in 1970. Jo Siffert and Pedro Rodriguez in 1971. Jo Bonnier in 1972. Francois Cevert in 1973. Peter Revson and Silvio Moser in 1974. Mark Donahue in 1975. Tom Pryce in 1977. Ronnie Peterson in 1978. Patrick Depailler in 1980. Gilles Villeneuve and Ricardo Paletti in 1982. Elio de Angelis in 1986. Nicki Lauda was maimed in a fiery crash, Clay Regazzoni was crippled for life, Moss suffered an accident that ended his career and nearly his life.

|

| Barry Kalb | © 1999 Atlas Formula One Journal. |

| Send comments to: bkalb@asiaonline.net | Terms & Conditions |

Barry Kalb is a veteran journalist of 20 years' experience (the Washington Star, CBS News, Time Magazine) and a motor racing fan - especially Formula One - for almost 40 years. He currently resides in Hong Kong. | |

Among the greatest drivers of all time, none is better known today - thanks in large part to satellite television broadcasting - and almost none is more controversial than the Brazilian, Ayrton Senna.

Among the greatest drivers of all time, none is better known today - thanks in large part to satellite television broadcasting - and almost none is more controversial than the Brazilian, Ayrton Senna.

That is a statement more of emotion than of reason. Who can say that any one driver was the greatest? But Senna, possibly along with Nuvolari, was certainly the driver most dedicated to the sport. In fact, he seems to have had little life at all outside racing and his family.

That is a statement more of emotion than of reason. Who can say that any one driver was the greatest? But Senna, possibly along with Nuvolari, was certainly the driver most dedicated to the sport. In fact, he seems to have had little life at all outside racing and his family.

Senna's death during the race was seen in real time by viewers all over the world, making it far more immediate to most of today's motor racing fans, if not more heart-rending, than those of dozens of racing drivers before him. Amid the world-wide anguish that followed the accident, one could have gotten the impression that motor-racing deaths were something out of the ordinary. To the contrary, death has been an almost companion of the Grand Prix driver. Ken Purdy counted some 50 racing deaths among top drivers between 1946 and 1963. At least one Formula One driver was killed on the track almost every year between 1950 and 1982.*

Senna's death during the race was seen in real time by viewers all over the world, making it far more immediate to most of today's motor racing fans, if not more heart-rending, than those of dozens of racing drivers before him. Amid the world-wide anguish that followed the accident, one could have gotten the impression that motor-racing deaths were something out of the ordinary. To the contrary, death has been an almost companion of the Grand Prix driver. Ken Purdy counted some 50 racing deaths among top drivers between 1946 and 1963. At least one Formula One driver was killed on the track almost every year between 1950 and 1982.*

Yet the fact was, by the time the teams assembled at Imola for the San Marino Grand Prix in May of 1994, nobody active in Formula One had seen one of his colleagues die in a race. Senna and Berger, the old men of racing that weekend, had both started their grand prix careers two years after Paletti's death. By all accounts, many of the drivers were seriously shaken by Ratzenberger's death during qualifying the day before the race, none less so than Senna. It is possible, faced suddenly with this almost forgotten reality of racing, that he might have modified his driving habits in the future - not to go any slower, for that was not within him, but to drive less recklessly.

Yet the fact was, by the time the teams assembled at Imola for the San Marino Grand Prix in May of 1994, nobody active in Formula One had seen one of his colleagues die in a race. Senna and Berger, the old men of racing that weekend, had both started their grand prix careers two years after Paletti's death. By all accounts, many of the drivers were seriously shaken by Ratzenberger's death during qualifying the day before the race, none less so than Senna. It is possible, faced suddenly with this almost forgotten reality of racing, that he might have modified his driving habits in the future - not to go any slower, for that was not within him, but to drive less recklessly.