|

|

|

GRAND PRIX REDUX: The Italian Stallion Does Maranello | |

| by Thomas C. O'Keefe, USA | |

|

Sylvester Stallone is scheduled to begin the production of a new movie about Formula One, the first film to be done on the sport since John Frankenheimer's movie "Grand Prix", which was filmed during the 1966 season. By coincidence or design, Grand Prix seems to be enjoying a renaissance itself; the movie has been aired recently on several TV stations around the world, and is also now available on home video. In a two part article*, Thomas O'Keffe explores the legacy of "Grand Prix" and the possibilities for Stallone to repeat the success of the earlier movie. * Part One can be found here Part II

Paul Newman, actor, Indy Car team owner, successful SCCA/Trans Am driver, and star of the racing movie "Winning" (1968), put it best in describing the quandary facing Sylvester Stallone in making a Formula One movie: "I don't know that there has been a great movie about racing. The movies either have great stories and not so great racing, or the other way around. The really great personal story with great racing footage has yet to be accomplished." While John Frankenheimer's 1966 "Grand Prix" gave us "great racing footage," the story lines were weak; it will be left to Sylvester Stallone to see if he can also meet the other part of the Paul Newman test, to develop a "great personal story" that would presumably explore what propels a person to race in Formula One. Judging from his public comments on the subject, Stallone's plan seems to be to do for the sport of Formula One racing what he did for the sport of boxing in Rocky: explain why people do it, what fuels their passion, the vicissitudes they suffer along the way and the other people they affect while the drivers pursue their dreams. In an interview with Martin Brundle published in "The Daily Damon", Stallone gave us a glimpse of his thinking in describing the characters he will use in the film:

"Well, actually there's about three different drivers in the movie. One is about 22, one at 30 and another slightly older driver. I play a Mario Andretti type who's just there for the last 8 races. It's about his whole life and passing the banner to another driver and how different generations have different attitudes towards racing and the commercial side of things as well. It's kinda like Rocky in that it's more about personalities than boxing, but boxing was a very big part of it. I'm gonna try and instill the same things in Formula One, so you really understand the personalities - and the incredible psychological aspect of the sport." He also indicated one of the characters would remind us of Jacques Villeneuve:

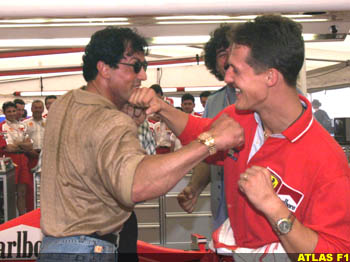

"I'm using [Jacques] as a prototype for the film. I'm a big fan of Hakkinen because he's done well considering what he's had to come back from. Michael Schumacher is like Picasso out there. Damon Hill, a real gentleman and such a great, great driver." Stallone, like Frankenheimer, has a lot to work with, given the context in which the movie will be made, because his Formula One film is being made in another classic era, with great teams and personal rivalries that are ongoing, great actual race footage to draw from and blend with the inevitable Hollywood special effects footage, and a host of interesting venues to choose from in focusing the film. Indeed, in some sense, Stallone has almost too much good material to work with in these particularly interesting years of Formula One, both as to the race footage and as to personalities that populate the pit area, to the point where Stallone faces a classic businessman's dilemma: does he make or buy? He has purchased a bundle of rights from Bernie Ecclestone in order to do the film, presumably including the footage taken at every race by those people from Formula One Administration with their silver outfits and cameras that you see at each track filming the race.

As an example, for those looking for crash and burn footage and exciting footage generally, how could Stallone improve upon Spa 1998 (both the first lap carbon-fibre meltdown and the later Schumacher/Coulthard rear-ender accident); the WurzFly overr at the Senna chicane in Montreal; Hakkinen skidding backwards through the grass and gravel traps at Monza; Schumacher going off at Austria over a dirt mound, pitting for a new nose and racing back through the field; Damon Hill weaving menacingly to harass Schumacher in Canada; the breathtaking three-stop pit strategy of Ferrari at Hungary that won the race; the Ferrari 1-2 at Monza and the Schumacher/Wurz toe-to-toe incident at the Loew's Hairpin at Monaco. The odds would suggest that the 1999 season could not hope to produce such actual race footage and the scriptwriters could hardly do better than what we have already witnessed the last two seasons. Who could improve on the circumstances and race footage that led to Michael Schumacher attempting to take out Jacques Villeneuve at Jerez when the 1997 World Championship came down to that one aggressive pass by Villeneuve and the desperate (and clumsy) thrust by Schumacher to fend it off. And who could create characters and personalities more vivid and textured than the drivers who are currently in Formula One, including Villeneuve himself, iconoclast andgrungye dressing GenXer that he is, son of a famous father, who died in a Formula One car. Who could improve upon Michael Schumacher as a foil for the Nordic Hakkinen or the straight-laced Coulthard. Michael Schumacher is an almost Shakespearean character, Germanic - almost bionic - in his controlled and single-minded approach to racing who can nonetheless lose control and be capable of assault and battery on Coulthard in the pits at Spa or out on the race track in the growing number of incidents like Jerez that have marked (indeed, marred) Schumacher's career. And for sheer drama, how about the Bionic Man succumbing to nervousness on the starting line of the last race of the season with the Championship hanging in the balance, slipping the clutch and stalling out, thus setting up a blistering run from the back of the field, just like the last scene in "Grand Prix". Throw in the inimitable Bernie Ecclestone as Formula One's Godfather, the mercurial Eddie Jordan, the wheelchair-bound Sir Frank Williams and scholarly Ron Dennis as team owners, irascible Eddie Irvine, the temperamental Jean Alesi, the voluble Alex Zanardi, supermarket-heir-turned-race driver Pedro Diniz and the inscrutable and talented "Tiger" Takagi - and you have a ready-made DramatisPersonaee within which to cast the real actors who will be the film's main characters.

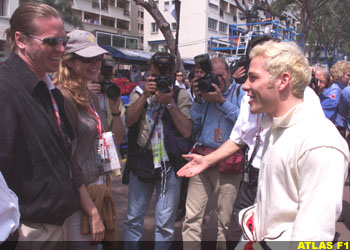

With the current crop of attractive and interesting Formula One drivers, it would seem inevitable that a representative sampling of drivers would be offered scenes or small parts playing themselves, as modified by the script. Even brief appearances by the real drivers would add a more genuine feel to the film; it might even turn out that some of them are decent actors since today's drivers grew up under Kleig lights due to sponsor obligations and the pervasive media coverage of Formula One. Just as we are disappointed today that a film like "Grand Prix" made in 1966 did not include much of Jimmy Clark or Jack Brabham, today's race fans will be surprised if the Schumachers, Hakkinen, Damon Hill and Villeneuve do not appear in the film. And since the film is bound to be promoted worldwide, Tiger Tagaki should be seen as should members of the South American contingent. The partnering of Stallone's production company with a few core race teams to build the story line around would also seem logical and inevitable. "Grand Prix" featured Ferrari and BRM and the quasi-Honda Yamura; in today's context, Ferrari and McLaren are the obvious counterparts; how about a cameraman in the back seat of the McLaren two-seater, following the race action, eyeball-to-eyeball! But working with a new team like British American Racing might be a better bet and a more natural ally, as would a well-financed engine manufacturer like Honda which will be returning to Formula One just as Stallone's film goes into production. Given the marketing and sponsorship aspects of Formula One which are now central to the sport (and which did not even exist when "Grand Prix" was filmed), it may turn out that teams might actually compete to become partners with the film production company. Since a few carbon-fibre melee's are doubtless in the offing in the course of making the film, why not have available to the film production company the cars from last year to spare, or build more with the autoclaves and factories teams have at their disposal.

The Montreal circuit would also seem to be a logical choice given the current penchant for producing movies in Canada because of financial considerations, the excellence of the circuit and its accessibility to the rest of the World. (Frankenheimer seems to have staged at least one of the six races he covered in "Grand Prix" at a track where an actual Formula One race was not held that year. The French Grand Prix was held at Rheims in 1966; "Grand Prix"'s French Grand Prix was held at Clermont-Ferrand, a track where the 1965 race was held.) Happily, all these tracks could produce thousands of people in the stands at the drop of a hat to create the feel of genuine race weekend. Indeed, if Stallone chooses to "make" - rather than buy - a Formula One movie on his own without incorporating the actual Formula One circus at all, there are enough cars and racetracks to do so in England alone. And if the Indianapolis Motor Speedway has completed the 2.53 mile Formula One circuit now on the drawing boards, the famous central Indiana racetrack which modestly boasts that it is the site of "The Greatest Spectacle in Racing," would seem to be an obvious choice as one of the races to feature in Stallone's film. Finally, we come to the most difficult challenge facing Stallone: how to explain how Formula One drivers come to be and what propels them to risk their lives in pursuit of a World Championship, "the great personal story" Paul Newman says has yet to be told. One answer - however heretical it may sound - is that there is no There there, no great personal story to reveal when it comes to this sport, that it is just a bunch of what would otherwise be border-line juvenile delinquents from various countries who were better than their school chums at racing their bicycles or go-karts and taking risks generally and have now turned into Playboys of the Western World.

"What is it about this paradoxical sport - so technologically controlled yet so patently unpredictable - that holds millions in thrall across the earth? What grips our collective imagination so tenaciously? What is the vehicle for explaining the paradox and the ingredients that go into making a World Champion? Instead of going with the traditional Tom Cruise-like character in "Top Gun", perhaps Stallone should try a novel device such as following the travails of an accomplished woman race driver trying to break into Formula One, to illuminate what motivates the psyche of a driver. Or perhaps a character analogous to Stallone's Rocky who comes out of nowhere to succeed against the odds, or an ex-driver who because of circumstances that develop during a season gets a second chance to prove himself and appreciates all the more what it means to be one of the twenty some people in a world of billions that is privileged to drive in Formula One. Whatever the dramatic or cinematic technique and conventions ultimately employed to make the Stallone film, there is sure to be a guaranteed audience for it worldwide, from Cannes to Caracas, and if it is done well, it might even make the sport understandable and appealing in that most remote of countries - the United States of America - where for reasons that remain mysterious, Formula One has never really established itself with race fans, who continue to be more enamored of NASCAR and Indy Cars. Since Stallone managed to make five films about boxing, most of them interesting even to the non-boxing fan and some of them brilliant, he surely can do the same for Formula One. 350 Million Formula One fans all over the world wait with baited breath for the worthy successor to "Grand Prix", appearing sometime in the Millennium at your local theater.

|

| Thomas C. O'Keefe, Esq. | © 1999 Kaizar.Com, Incorporated. |

| Send comments to: tcokeefe@worldnet.att.net | Terms & Conditions |

| Thomas C. O'Keefe is a lawyer who practices law in the U.S. Virgin Islands and in New York. He became captivated with Formula One and visiting race-tracks after watching Jimmy Clark cross the finish line to win the Indianapolis 500 in 1965 and following his F1 career thereafter. | |