|

| |||

|

Taking the Lid Off F1 Formula One Technical Analysis | ||

| by Will Gray, England | |||

|

Atlas F1 presents a series of articles by certified engineer Will Gray, that investigates in greater depth all the technical areas involved in design, development, and construction of a Formula One car.

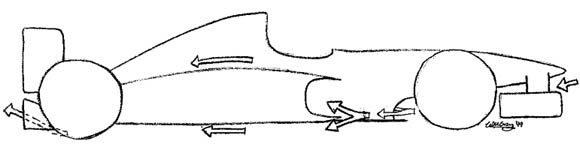

Why is an F1 car shaped the way it is? It's not because the Technical Director likes the curves (although to some extent it can be!), it's because that is the shape that, with the resources the team has to explore the area, is the most efficient at getting through the air obstacle. Rules and regulations help to clone the cars, with 'no-go boxes' stipulated all around the car - rules declaring where bodywork can and can't exist, but ingenious designers can always spot loopholes in these!

The flow of air underneath the car is one of the most important areas of the aerodynamic design. Air travels under the nose and the underside of the front chassis to the chin, which splits the air between that which travels through the sidepods for cooling, and that which goes under the car's floor. At the end of the floor, the air meets the diffuser, which returns it to the outer airstream. This route will now be described in more detail.

The Nose and Chin:

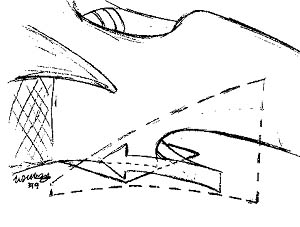

The raised nose - which when it first came out looked like a handlebar mustache - allows the air to flow, undisturbed, to an air splitter (the chin) positioned under the cockpit, at the start of the floor. Before, the front chassis and nose ran flat to the floor, with the aim of obtaining downforce from this area. Instead, Tyrrell saw that by moving these obstacles out of the way, better airflow to the floor created more downforce. The nose was raised, the front wing suspended on pylons, and the front of the chassis was smoothly curved from the high nose down to the chin at floor level. The chin, shown in the diagram, is a semi-circular scolloped face, with a flat, horizontal surface sticking out underneath it. The face guides the undisturbed air around and under the sidepods, and the flat surface prevents the air from being encouraged to go anywhere else. The current school of designers are always looking for more air under the floor, as it is here that the greatest and most efficient downforce can be produced - the nose is now something they want to get out of the way.

Front Chassis:

Floor:

The closer the floor is to the track, the more downforce it will produce due to ground effect, so to reduce the downforce created by the floor, the rulemakers stipulate that it is raised from the track. This is enforced by a plank of wood (yes, wood!), positioned underneath the car at cockpit width, running from the chin to the rear.

The Nose and Chin:

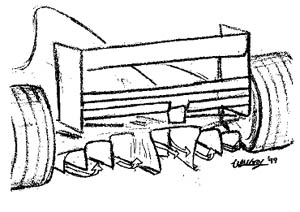

The main aim in diffuser design is to take it to its limit, and not beyond. If the slope of the diffuser is too steep, we will have flow separation (the flow will no longer follow the surface), causing extra drag. This may not occur in all areas, however. In the outer edges of the diffuser, the air, which has traveled under the car along the outer part of the floor, will have mixed with, and been slowed by, air from outside the floor. Towards the centre, however, the air flows faster, as no extra air has reached that area. For this reason, the diffuser consists of varying slopes, depending on the curve the air can follow before separation.

With rear wing elements helping suck the air from under the car, and the close-packed nature of the car in this area, it tends to be knowledge-inspired trial and error development which changes the shapes of the diffuser - to get a good one takes a lot of time and effort...and a touch of luck! Previous Parts in this Series: Parts 1 & 2 | Part 3 | Part 4A | Part 4B | Part 4C | Part 5A | Part 5B | Part 6A | Part 6B | Part 7A | Part 7B-1 | Part 7B-2

|

| Will Gray | © 2000 Kaizar.Com, Incorporated. |

| Send comments to: gray@atlasf1.com | Terms & Conditions |